B.C. Historical Quarterly, April, 1939

https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/bch/items/1.0190667#p28z-3r0f:%22british%20columbia%20historical%20quarterly%22%20AND%20%22april,%201939%22

The Negro Immigration Into Vancouver Island In 1858.

F.W. Howay

California was from the beginning a free State. Its constitution provided that there should be no slavery within its boundaries. Its population was a heterogeneous collection of adventurers from every State in the union and every nation of the globe. Its people were more interested in placer than in politics. This does not imply that they were not concerned with public matters, but merely that the pursuit of the yellow root of evil occupied the center of their activities.

In 1850 and 1851 the State Legislature had taken what appears to have been the first steps against the negro. By these Acts negroes were disqualified from giving evidence against white persons. It speaks well for the general standard of honesty that these statutes did not create or at any rate encourage a condition of lawlessness; for their effect was to deprive the negroes of the ability to protect their property from spoliation by the white man. From time to time attempts were made, but unsuccessfully, to effect a modification of this law. “It is maintained in force, “said the Daily Evening Bulletin, San Francisco,[i] simply because a class of our people were brought up instates where negroes were not allowed to testify, not because they were negroes, but because they were slaves, and their vehement adherence to the prejudices of their birthplace has affected the popular mind.”

In 1852 the Legislature passed a Fugitive Slave Act,[ii] providing for the arrest of any slave found in the State who might have escaped from his master. It authorized any Judge, upon oral evidence or other satisfactory proof, to issue a certificate upon which the fugitive slave could be returned to servitude, but he must be removed from the state. It contained a provision that “In no trial or hearing under this Act shall the testimony of such alleged fugitive be admitted in evidence.”

The negroes of the State in convention in Sacramento in 1856 denounced without avail these prohibitions against their giving evidence, which left them without the means of protecting their property, persons or liberty, and placed them in the same position as criminals. The feeling of injustice is deepened when it is recalled that the negroes of the State, in 1857, owed taxable property of the estimated value of about $5,000,000.[iii] In voting upon the constitution of Oregon as a State, in 1857, its people had resolved that free negroes be excluded. This gave the Evening Bulletin[iv] the opportunity to remark: “It is much better to keep them away than to let them come, and deprive them of all civil rights and the power of defending themselves or their property as is done in this State.” In his valedictory address in January 1858, John Neely Johnson, the “Know-Nothing” Governor, impressed with the unfairness of the situation, recommended that “the law excluding the testimony of negroes and Chinamen should be abolished.”[v]

The question of negro slavery in California was discussed by the newly-elected Governor, John B. Weller, a Democrat, in his inaugural address, in January, 1858. The burden of his remarks was along standard Democratic lines; that California had decided that slavery should not exist within her boundaries; that the agitation for the abolition of slavery was unwise, inasmuch as it was an attempt by one state to dictate how another should handle its own affairs; and that such agitation tended to weaken the ties of affection between the States.

Almost coincident with these pronouncements of the governors arose a cause célébre – the case of Archy Lee – which in the end set the heather on fire. The first the public knew of the matter was on January 11, 1858, when it was learned that this negro boy had been arrested as a fugitive slave and held for deportation to Mississippi, and that the coloured population were greatly excited. They at once became vitally interested in the proceedings for his release on habeas corpus. The facts, As first deposed by his master, one C.A. Stovall, of Mississippi, were that Archy was his body servant, and had been a slave on his plantation for many years; that he set out for the West in January 1857, taking the boy with him; and that, though since his arrival in California he had been resident in Sacramento, he was in reality travelling for his health, and with no intention of remaining permanently in the State. The slave boy, it was said, was worth $1500 in Mississippi. It further appeared that Stovall had purchased a ranch in Carson Valley, on which he had placed some cattle that he had brought across the plains; that he had been in Sacramento since October 1857; had hired a school-room and advertised for pupils; that Archy had been working for various persons, but Stovall had collected his wages. The case was transferred from the State Court to that of United States commissioner George Pen Johnston. He found, upon the facts as stated, that Archy had not escaped from his master and fled to California, but had been knowingly brought by Stovall, his owner, into a free state, and that therefore he had no jurisdiction, as the negro was not a fugitive slave within the meaning of the Act. He, accordingly, returned the case to the State Court.

At this time the State Legislature was in session. Both Houses were overwhelmingly Democratic. Of the thirty-five members of the Senate twenty-seven were Democrats; and of the eighty members of he Assembly sixty-six were also Democrats.[vi] To aid the slave-owner, Stovall, Mr. A.G. Stokes, senior member for San Joaquin County, introduced on January 18 a Bill providing that where any slave “shall be brought or may have been heretofore brought” by his owner into California, if only travelling through the State or in good faith sojourning therein without the intention of permanently residing, and such slave escapes, he shall not be free, but should be delivered up to his owner. The opponents of the Bill claimed that it not only tolerated but actually legalized slavery in California. The Bulletin expressed the belief that five-eighths of the Democratic members of the lower House were from the Northern States, and on principle and by education opposed to slavery. On February 2, Mr. stokes introduced another Bill “to prohibit the immigration of free negroes and other obnoxious persons into this state and to protect and regulate the conduct of such persons now within the state.”

To add fuel to the fire the question of the attendance of coloured children in the public schools of San Francisco came before the Board of Education, which on February 17 ordered that they should not be permitted to attend any school except that established for them and directed those in attendance at any public school to be removed therefrom.

While these matters were going on, Archy’s case reached the Supreme Court of California and was heard by Chief Justice Terry and Judge Burnett. Terry was a “Know Nothing,” but Burdett was a Democrat. They rendered a remarkable decision. They found that Stovall was not a visitor nor a traveller; whence it would seem to follow that he had the only other status; that of a resident. It resulted therefrom that a resident of a free State was striving to maintain slavery within its boundaries. But as this was the first case to arise and as Stovall was in poor health and in poor financial condition “we are not disposed to rigidly enforce the rule for the first time. But in reference to all future cases, it is our purpose to enforce the rules strictly according to their true intent and spirit.”[vii]

The decision was received with the jeers and sneers which it deserved. It was painfully manifest that Judge Burnett had permitted his belief that slavery was a proper and laudable institution to override his sense of justice and right. Judge Baldwin, his successor, characterized the decision as “giving the law to the North and the nigger to the South”; and subsequently prepared a humorous abstract of Archy’s case in which he said that the constitution does not apply to young men of weak constitution travelling for their health; that it does not apply for the first time; and that the decisions of the Supreme Court are not to be taken as precedents.[viii] The Bulletin was fearlessly outspoken. It characterized the two judges as “Supreme Mugginses,” and called for their impeachment. The Chief Justice it dubbed an “ignorant bully,” and declared that it was time that steps should be taken to purge and purify the Supreme Court.

Oddly enough a similar case[ix] came before Judge George H. Williams of Oregon – also a Democrat – in 1853. A coloured family of Polk County applied for release on habeas Corpus from their Missouri owner who had brought them into that free State and held them as slaves. Judge Williams decided that the Oregon law of 1844 was valid and constitutional and that its declaration that there should be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the State operated to the release of slaves brought there by their masters.

Despite the noise and clamor with which the decision in Archy’s case was received, Stovall had his slave in his possession in California – the constitution notwithstanding. He kept the boy secretly in goal in San Joaquin County; this fact was discovered, and a writ of habeas corpus again applied for; but before it could be served Stovall whisked Archy out of that confinement. He kept Archy hidden away until March 4, 1858, when the steamer Orizaba was about to sail from San Francisco for Panama. In some way the negroes became aware of his purpose. They caused a warrant to be issued charging Stovall with kidnapping the boy. Police officers with the warrant went aboard the Orizaba. When the steamer was off Angel Island in the harbour, a small boat with Stovall and his slave came off to her. As the officers arrested him, he protested, saying that the Supreme Court had awarded him the boy and he would be d_____d if any Court in the State would take him away. Great was the excitement in the city over the occurrence. The coloured people were out in strength, and Archy was the observed of all beholders. To increase the tensity of the situation a number of petitions had been presented to the Assembly, in accordance with ex-Governor Johnson’s suggestion, requesting the repeal of the law which prevented the negroes from giving evidence in matters in which a white man was concerned; and on the very day that Archy and his master were taken from the Orizaba the Judicial Committee of the Senate had reported adversely.

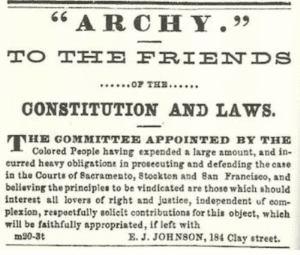

Events now began to move rapidly. The next day after the Orizaba incident the following notice was posted up on the Athenaeum on Washington Street and in other places frequented by coloured people.

NOTICE! ! !

There will be a public meeting of the coloured citizens of

San Francisco this (Friday) evening, March 5th at Zion, M.E.

Church, Pacific, above Stockton St., to commence at 8 o’clock.

Signed by a Committee.

The meeting was largely attended. The church was filled with coloured people and a sprinkling of whites. An appeal was made for funds to carry on the fight for Archy’s freedom. The sum of $150 was subscribed, and a committee appointed to solicit further contributions. On March 8, the application for Archy’s release on habeas corpus came up. The Court-room was densely crowed and a great interest was manifested in the case. When Judge Frelon denied Stovall’s application to dismiss the writ, his council consented to Archy’s discharge. He was immediately  re-arrested as a fugitive slave and the matter came again to the Court of United States Commissioner George Pen Johnson. There was great excitement among the negroes. The United States marshal, fearing a tumult, called to his assistance a considerable number of police officers. Much confusion ensued. As poor Archy was being taken away by the marshal and his men there was a rush and a press, and a large crowd followed through the streets while the boy was forced along towards the marshal’s office. Several excited coloured individuals were arrested for assault and battery and creating a disturbance; but nothing like a rescue was attempted. Everybody was excited.

re-arrested as a fugitive slave and the matter came again to the Court of United States Commissioner George Pen Johnson. There was great excitement among the negroes. The United States marshal, fearing a tumult, called to his assistance a considerable number of police officers. Much confusion ensued. As poor Archy was being taken away by the marshal and his men there was a rush and a press, and a large crowd followed through the streets while the boy was forced along towards the marshal’s office. Several excited coloured individuals were arrested for assault and battery and creating a disturbance; but nothing like a rescue was attempted. Everybody was excited.

Day by day the case dragged its slow length along; there were delays and adjournments. But the coloured people were always in attendance to catch the least word or movement. A month went by before the matter was decided. In that interval the interest shifts to the Legislature. The two Bills introduced by Mr. Stokes were dropped in favour of one brought in on March 19 by Mr. J.S. Warfield, the senior member for Nevada county. It is described in the journals[x] as a Act to restrict and prevent the immigration and residence in the State of negroes and mulattoes. No mulatto was thereafter to be allowed to immigrate to California; if any did and were found therein, they were to be deported. It provided that the sheriff could hire to any person “for such reasonable time as shall be necessary to pay the costs of the conviction and transportation from this state before sending such negro or mulatto therefrom.” All coloured people then in the state were to register; failure to do so was to be a misdemeanor. Those already in California might depart without molestation if they went at once. Every registered negro must be licensed, and any person employing an unlicensed negro would be liable to a heavy fine. There were many supporters of such legislation, both within and without the House. When one of the members asked where the coloured people then in the State were to be sent, a voice replied, “Send them to the devil.”[xi]

This Bill, like its predecessors, was nevertheless strongly criticized. It was claimed that the migration of a negro from one State to another could not be, or be made, a crime; that the negroes were already there and that the provision that new comers could be arrested and their services sold at auction to the lowest bidder in order to raise the money for their deportation was the thin edge of the wedge of slavery. It was contended that it was oppressive to pass such a retroactive law, which would drive them out of employment, for no one would dare to employ one of them lest it be discovered that such a negro had no license and the employer be thereby rendered liable to a heavy fine.

One of the negroes in a letter to the Bulletin,[xii] signed W.M.G. (probably W.M. Gibbs, a man of marked ability), took up the cudgels for his people and put forward their case in a manly, outspoken fashion. He concludes in this wise:

“Let the bill now before the Legislature take what turn it may, the coloured people in this state have no regrets to offer for their deportment. Their course has been manly, industrious, law-abiding. To this Legislature and the press that sustains them be all the honour, glory, and consequences of prosecuting and abusing an industrious unoffending, and defenceless people.

But to return to Archy and his case. Stovall, strange to relate, now made an affidavit altogether different from that which he had made when he launched the original proceedings in the preceding January. Then he had said that he had brought Archy with him from Mississippi. He now changed his front and to give the poor boy the appearance of a fugitive slave, he declared that Archy had assaulted a person in Mississippi with a knife and that he had, in consequence, fled from that State in January 1857. Stovall further declared that after Archy had disappeared he set out for California, over the plains, and that at the crossing of the North Platte River he accidentally encountered Archy, and together they journeyed to Sacramento. By virtue of the law of 1851 Archy was, of course, prevented from controverting any of these statements. However, George Pen Johnston, the United states Commissioner – a Democrat too, be the way – had not forgotten the first account that Stovall had given; the manifest contradictions could not be explained. To the great surprise of many with anti-negro feelings Johnston held, after mentioning the variations in the two stories told by Stovall, that in any event he could not decide that Archy was, in any sense, a fugitive slave who had escaped to California; and on April 14, 1858, he granted Archy his freedom. Great was the jubilation of the coloured people.

But at the same time they were at a white heat; for though they had been victorious in Court the Legislature had to be reckoned with, and the proposed drastic legislation against them was slowly making its way towards becoming a law in some form or other. Their very existence and their freedom were in jeopardy. The only safe course appeared to be to remove from the State. On the very day of Archy’s release a large meeting appeared to be to remove from the State. On the very day of Archy’s release a large meeting was held in Zion Methodist Episcopal Church. The question was not whether they should emigrate, but whither they should emigrate, and it was discussed at length. The choice lay between Vancouver Island – then a separate British Colony – and Sonora in Mexico. They declared that “they would not be degraded by the enactment of such an unjust and unnecessary law against them by their own (American) countrymen.” The further consideration was deferred until the next day, when they again assembled in the same church. The first business then taken up was the raising of money to pay the deficit in the expenses of Archy’s case. While the collection was being taken up they sang a hymn of rejoicing. It was an adaptation of Charles Wesley’s well-known words.

The Year of “Archy Lee”

A song of Rejoicing for Archy’s Deliverance

Blow ye the trumpet! Blow!

The gladly solemn sound,

Let all the nations know

To earth’s remotest bound

The year of Archy Lee is come

Return, ye ransomed Stovall, home.

Exalt the Lamb of God;

The sin-atoning Lamb;

Redemption by His blood

Through all the land proclaim.

The year of Archy Lee is come

Return, ye ransomed Stovall, home.

Ye slaves of sin and hell.

Your liberty receive;

And safe in Jesus dwell,

And blest in Jesus live.

The year of Archy Lee is come

Return, ye ransomed Stovall, home.

The gospel trumpet hear –

The news of pardoning grace;

Ye happy souls draw near;

Behold your saviour’s face,

The year of Archy Lee is come

Return, ye ransomed Stovall, home.

The appropriateness of the adjective “ransomed” as applied to Stovall (the slave-owner) is scarcely apparent, but the spirit behind the hymn must plead excuse. The money came down thick and fast as the hymn was sung. Then followed another – an atrocious bit of composition; but what it lacked in obedience to the rules of rhyme and rhythm it made up for in its genuine feeling of thankfulness for the victory in court. It was based upon Thomas Moore’s well-known Miriam’s Song.

A Song of Praise

For the Benefit of Those Named Therein

Sound the glad tidings o’er land and sea–

Our people have triumphed and Archy is free!

Sing, for the pride of the tyrant is broken;

The decision of Burnett and Terry reversed.

How vain was their boasting” Their Plans so soon broken;

Archy’s free and Stovall is brought to the dust.

Praise to the Judges and praise to the lawyers!

Freedom was their object and that they obtained.

Stovall has shown it was time to be moving;

He left on the steamer to lay deeper plans.

But there was a Baker, a Crosby, and Tompkins,

Before Pen Johnston and did plead for the man.

In the discussion it was stated that in the past year scarce twenty-four coloured people had arrived in California from the free states. Upon this fact the argument was built that an ulterior motive lay behind the heinous law then before the Legislature. Though at the outset the majority seemed to favour emigration to Mexico the feeling gradually swung round to the nearest British procession, Vancouver Island.

On April 19 the third meeting was held. By this time they had formulated their plans, and it was now resolved to send an advance party of sixty-five persons to Vancouver Island to ascertain whether the British possession would receive them as residents; and if so, these forerunners were to purchase as much land as possible with a view to permanent settlement under British protection. Mr. M.W. Gibbs, one of the negroes, then delivered a farewell address to the vanguard who were to sail on the steamer Commodore on the following day. The Bulletin[xiii] dealing with their departure, said editorially:

All this puts one in mind of he Pilgrims and the address of Pastor Robinson, when those adventurers embarked for their new home across the seas. When the coloured people get their “poet” he will no doubt sing of these scenes which are passing around us almost unheeded, and the day when coloured people fled persecution in California may yet be celebrated in story. This is an important epoch for this class of our inhabitants. The sixty-five yesterday went off in the Commodore, and are now pushing toward the north, bearing their lares and penates to found new homes. It is said that if eh attempt to make a settlement on Vancouver’s island should prove abortive, a number who favour P. Anderson’s proposition for a settlement in Sonora, Mexico, will make an attempt in that direction. Whatever may be their destiny, we hope the coloured people may do well.

While this advance guard of negroes were journeying to the land of freedom, the Assembly was just closing its session. The dreaded Warfield Bill (which, as has been shown, had been substituted for those introduced by Stokes) failed to become law, but that was merely because the Senate had tacked on some small amendments and before these could be considered and approved by the Assembly, the time of prorogation had arrived and the Bill was lost in the hurry that always accompanies the closing days of any session. Th House, as has been said, was overwhelmingly Democratic; a large majority favoured this legislation; any thought, therefore, that its failure to become law was in any way caused by the negro emigration is entirely gratuitous. It was even said that the pro-slavery supported were so in earnest in the matter of Archy that some of hem sensing that U.S. Commissioner Johnston would order his release, strove to provoke a duel with him, in order effectually to prevent a favourable judgement for the negro boy, by disposing of the Commissioner on the “field of honour”.

On May 6, 1858, another meeting of the negroes was held in the usual place, Zion Methodist Episcopal Church, to hear the report of the delegates to Vancouver Island. About 300 persons were present, of whom some fifty were whites. The report was satisfactory. It was stated that the forerunners had been received “most cordially and kindly by His Excellency the Governor, and most heartily welcomed to this land of freedom and humanity”; that land could be obtained at twenty shillings and acre; one-quarter in cash, and the remainder in four annual payments with interest at five per cent, but with no tax on the land until full payment; that land-holders after a residence of nine months had the right of electoral franchise, of sitting as jurors, and all the protection of the law as citizens of the Colony, but that to enjoy the complete rights of British subjects they must reside seven years and take the oath of allegiance; and that town lots 66 feet by 132 could be bought for fifty dollar each. Another report stated that within an hour after they had secured a house in Victoria, they had held a solemn religious service in thankfulness for their improved prospects; that they had a visit from the Rev. Edward Cridge, the resident Episcopal minister, who welcomed them to their new home and expressed his pleasure at having so many Christian friends around him, that he had invited them to services of the Church of England and to his home, and, after offering to do anything in his power to aide them, had concluded his visit with a prayer for their well-being. It added that they had seen the land of the island, and that it was in every way suitable for their requirements. Another letter spoke of the beautiful situation and site of Victoria. It also stated that the Governor had authorized the writer to say that if they came to the colony they would have all the rights, privileges, and protection of the laws of the country; that there were two churches and two schools, one of which was taught by an educated Indian; that, in short, “It is a God-sent land for the coloured people.”[xiv]

Throughout the whole story one cannot fail to be impressed with the deep religious feeling of these people and their reliance upon God under every trial. This must plead in excuse of the flamboyancy of their language at times and of their metrical compositions, which sometimes “had in them more feet than the verses would bear.”

The meeting discussed and approved of these reports and of the “course of the Brethren in Vancouver’s Island.” Speeches were made, and great enthusiasm prevailed when it was agreed that they organize an Emigrant Society to enable their removal to the British colony. The plan was to raise $2500 by contributions of $25 each; to charter a vessel therewith and remove as a body to their new-found home. Following the precedent of the Declaration of Independence, they now prepared “A Declaration of the Sense of the Colored People”.[xv]

Whereas We are fully convinced that the continued aim of the spirit and policy of our Mother Country is to oppress, degrade, and entrap us. We have therefore determined to seek an asylum in the land of strangers, from the oppression, prejudice, and relentless persecution that have pursued us for more that two centuries in this, our mother country. Therefore, a delegation having been sent to Vancouver’s Island, a place which has unfolded to us in our darkest hour, the prospect of a bright future; to this place of British Possession the delegation having ascertained and reported the condition, character, and its social and political privileges, and its living resources. The mission in the highest degree credible they have fulfilled and rendered most flattering account to their constituents in their reports, in view of which it be resolve as follows:

Then follow twelve resolutions expressing thanks to the delegation, to Governor Douglas of Vancouver Island, and to the Rev. Edward Cridge, affirming their conviction that that island will prove a haven of rest, pledging loyalty to its laws and institutions and indicating the conduct to be pursued by the coloured people during their residence. The eighth and twelfth resolutions seem worthy of being reproduced in full.

- Resolution. That in bidding adieu to the friendships, early associations, and the thousand ties which bind mankind to the places of their nativity; we are actuated by no transitory excitement, but are fully impressed with eh importance of our present movement, and with our hearts filled with gratitude to the Great Ruler of the Universe, who has provided this refuge for us, we pledge ourselves to this cause and will make every effort to redeem our race from the yoke of American oppression.

- Resolution. That we now unitedly cast our lots (after the toil and hardships that have wrung our sweat and tears for centuries), in that land where bleeding humanity finds a balm, where philanthropy is crowned with royalty, slavery has laid aside its weapons, and the colored American is unshackled; there in the lair of the Lion, we will repose from the horrors of the past under the genial laws of the Queen of the Christian Isle.

As with these words the negroes shook the dust of California off their feet. Among those who went in the first contingent was the celebrated Archy, whose persecution had lit the fire. Doubtless he and his coloured brethren breathed freely as the coast of California sank from view. The number who emigrated had not been definitely ascertained. Vary shortly after the promulgation of the “Declaration of the Colored People” began the Fraser River gold rush of 1858 and the negroes were simply absorbed in the great crowd of eager adventurers hurrying to the latest El Dorado. Edgar Fawcett,[xvi] writing in 1912, estimated the number at 800, but this appears too large; the Rev, Matthew Macfie, a Congregational minister who came to Vancouver Island in 1859,[xvii] places it at 400; and this appears to be a closer approximation.

F,W. Howay

New Westminster, B.C.

[i] December 21, 1857.

[ii] Chapter 33 of Acts, 1852.

[iii] Daily Evening Bulletin, October30, 1857.

[iv] Ibid, November 16, 1857.

[v] Journals of Assembly, January 8, 1858, p 50.

[vi] Quarterly of the California Historical Society, IX, (1930), p 268.

[vii] Ex parte Archy, 9 California Reports, p 147.

[viii] T.H. Hittell, History of California, San Francisco, 1897, IV, p 245.

[ix] Holmes vs Ford; see Oregon Historical Quarterly, XXIII, (1922), p111 f.

[x] Journals of Assembly, March 11, 1858, p 408 (Notice of Bill).

[xi] Quarterly of the California Historical Society, IX, (1930), p 281 f

[xii] April 5, 1858.

[xiii] April 21, 1858.

[xiv] Daily Evening Bulletin, May 7, 1858.

[xv] Ibid, May 12, 1858.

[xvi] Edgar Fawcett, Some Reminiscences of Old Victoria, Toronto, 1912, p 215.

[xvii] Matthew Macfie, Vancouver Island and British Columbia, London, 1865. P 388.