FROM COLONY TO PROVINCE.

The Introduction of Responsible Government in British Columbia.

W.M. Sage.

The presidential address to the British Columbia Historical Association, November 18, 1938.

British Columbia Historical Quarterly, Vol. III, No.1

The years from 1866 to 1861 have been termed the “Critical Period Of British Columbian History.” The two colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia were united at the fiat of the Imperial Parliament. The union of 1866 was unpopular, especially upon the Mainland, and it did not succeed in solving economic problems of the United Colony. After the gold-supply had ceased to flow from the Cariboo, British Columbia sank deeper into debt. Three courses lay open to the colony: British Columbia might remain an isolated colony, having as her nearest neighbours, Red River on the east and Hong Kong on the west; she might follow what was alleged to be her “manifest destiny” and join the United States; or she might enter the Dominion of Canada. After much discussion and agitation and a little heart-searching, British Columbia decided to join with the Canadian Federation. Canada was desirous to extend her Dominion from sea to sea. The Imperial Government was most anxious to have British Columbia as a part

of Canada. After the death of Gov. Frederick Seymour, Gov. Anthony Musgrave was sent from Newfoundland to British Columbia to make certain that the necessary steps were taken so that British Columbia might secure entrance into the Dominion on mutually advantageous terms.

Amongst the problems discussed between the three representatives of British Columbia and the Dominion Government two stand out: The building of a transcontinental railway to join British Columbia and Eastern Canada, and the demand of the people of British Columbia for responsible government. The railway clause, number eleven, was finally inserted into the Terms of Union and mutually agreed upon by the British Columbia delegates and the Dominion Government. The other, responsible government was much more thorny.

To put the matter in a phrase – responsible government did not exist in British Columbia prior to Confederation. A Legislative Assembly had been set up in Vancouver Island in 1856 and had ceased to exist when the union of the colonies took place in 1866. During these 10 years the members of the Legislative Assembly of Vancouver Island had obtained the rudiments of a political education, but neither they nor Governors Douglas and Kennedy had succeeded in solving the constitutional problems which beset them. James Douglas and his dispatch of May 22, 1856, to Henry Labouchere Sec. of State for the Colonies, admitted that he possessed but “a very slender knowledge of legislation.” It was true; and the remark might apply rather well to the constitutional development of British Columbia prior to federation. Sir James Douglas was an “old colonial governor” who never progressed far beyond personal rule. The Legislative Assembly of Vancouver Island had only a limited control over finance and no control whatever over the actions of the executive. Under Gov. Kennedy the Assembly battled with the Governor over the question of the Civil List. British Columbia did possess a Legislative Council after 1864, but two thirds of its number were composed of officials and magistrates, and the five popularly elected members could never hope to dominate the Council. The Legislative Council of the United Colony was in the main opposed to Confederation. Amor De Cosmos, former member for Victoria District, ably assisted by John Robson, member for New Westminster, championed the cause of Confederation, but it was only the timely death of Gov. Seymour in 1869 which gave federation its chance.

A long debate on the Terms of Union with Canada took place in the Legislative Council of British Columbia beginning on Wednesday, March 9, 1870, and lasting until April 6. The deputation of three, all members of the Executive Council – Dr. John Sebastian Helmcken, from Victoria; Joseph W Trutch, Chief Commissioner for Lands and Works; and Dr. R. W. W. Carrall, from Cariboo, a Canadian by birth – was appointed by Gov. Musgrave to go to Ottawa and there discuss and, if possible, draw up mutually acceptable terms of union. At length success crowned the efforts of the British Columbia delegation and also of Her Majesty’s Privy Council for Canada. After the necessary steps had been taken and addresses had been forwarded to Her Majesty from the Parliament of Canada and the Legislative Council of British Columbia, Queen Victoria signed at Windsor Castle on May 16, 1871, an Order in Council admitting British Columbia as a Province of the Dominion of Canada. The date set for the formal admission was July 20, 1871.[i]

In the Confederation Debate of the Legislative Council of British Columbia in March – April, 1870, a long discussion occurred on the subject of responsible government.[ii] The Atty. Gen., Hon. Henry PP Crease, afterwards Sir Henry Crease, stated that responsible government did not form part of the Terms of Union, but claimed that “the question of the change of the Constitution of this Colony is one that lies between this Colony and the Imperial Government….”[iii] T. B. Humphreys, in Lillooet, and that John Robson, of New Westminster, spoke strongly in favour of responsible government. Humphreys laid down the proposition “no Responsible Government, no Confederation; no Confederation, no pensions.”[iv] Since the pension clause was vital to the officials, Humphreys’ proposition carried weight. John Robson maintained that the people of British Columbia were fit for responsible government, and continued his argument as follows: –

Look at the position this Colony would occupy under Confederation without the full control of its own affairs – a condition alone attainable by means of Responsible Government. While the other Provinces only surrender Federal questions to the Central Government, we would surrender all. While the other Provinces with which it is proposed to confederate upon mutual and equitable terms retain the fullest power to manage all Provincial matters, British Columbia would surrender that power. Her local as well as her national affairs would virtually be managed in Ottawa. Could a union so unequal be a happy and enduring one? The compact we are about to form is for life. Shall we take into it the germ of discord and disruption? The people desired change: but they have no desire to exchange the Imperial heel for the Canadian heel. They desire political manumission.[v]

Robson offered as an amendment to clause 15 of the proposed Terms of Union: –

Whereas no union can be either acceptable or satisfactory which was not confer upon the people of British Columbia as full control over their own local affairs as in enjoyed in the other Provinces with which it is proposed to confederate; therefore, be it resolved, That a humble address be presented to His Excellency the Governor, earnestly recommending that a Constitution based upon the principle of Responsible Government, as existing in the Province of Ontario, may be conferred upon this Colony, coincident with its admission into the Dominion of Canada.[vi]

Robson’s amendment, however, met with serious opposition. The question at issue was not whether responsible government, in itself, was superior as a form of government to rule by a governor and council, but whether or not responsible government should be included in the Terms of Union. Gov. Musgrave was convinced that responsible government should not be introduced into British Columbia until after Confederation. He had made his position quite clear in the following passage from the speech from the throne read at the beginning of the seventh session of the Legislative Council of British Columbia on February 15, 1870: –

The form of the local Constitution must be to some extent modified in Confederation with the other Provinces; and even in anticipation of that event, I think that an enlarged application of the principle of Representative Government to the composition of your Honourable House would be expedient. I have already, by Her Majesty’s permission, reconstituted the Executive Council by the addition of two Unofficial Members representing populous Districts, from whose advice I received valuable assistance. I shall go further in the same direction, and on the same principle. I shall ask for authority so to reconstitute the Legislative Council as to allow the majority of its Members to be formally returned for Electoral Districts. And to a Council so reconstituted I shall look for a final decision upon any terms to which the Government of Canada may express readiness to agree. Further than this I frankly admit I do not think that it would be wise to go. I have had experience of several forms of Colonial Government, and I have no hesitation in stating my opinion that the form commonly called “Responsible Government” would not be found at present suited to a community so young and so constituted as this. It is not known in any of the neighbouring States or Territories. Experience has shown that the system is expensive in its results, and its operation is not successful except in more advanced communities, with a population of more homogeneous character than ours. But it will of course, after Union, be open to the Local Legislature, with the concurrence of the Government of the Dominion of Canada, to adopt what modification it shall choose of the existing Constitution. I have declared my opinion to you with candour. I think you will appreciate my motive. I wish to aid only in what I believe will conduce to the welfare and prosperity of the colony.[vii]

His Excellency’s views were supported by the “official” members of the Council and also by some of the popular members. Joseph W Trutch, Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works, and subsequently the first Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia, spoke against Robson’s amendment and stated that “Responsible Government is not desirable, it is not applicable to this Colony at present; is practically unworkable.”[viii]

George A Walkem, a Canadian, agreed with the Chief Commissioner, as did Frank J Bernard, who summed up the situation in the following sentence: –

“It is beyond the question that the intelligent portion of the community are (sic) in favour of Responsible Government, but there is a great question in regard to its adaptation to the Colony. The words coming from His Excellency are worthy of careful consideration; they contain strong reasons against the introduction of Responsible Government.”[ix]

On division Robson’s amendment was lost, and in the final Terms of Union as amended in Ottawa and presented to the reconstituted Legislative Council of British Columbia on January 5, 1871, the clause in question reads as follows: –

- The Constitution of the Executive Authority and of the Legislature British Columbia shall, subject (to) the provisions of the British North America Act, 1867, continue as existing at the time of the Union until altered under the Authority of the said Act, it being at the same time understood at the Government of the Dominion will readily consent to the introduction of Responsible Government when desired by the Inhabitants of British Columbia, and it being likewise understood that it is the intention of the Governor of British Columbia, under the authority of the Secretary Of State for the Colonies, to amend the existing Constitution of the Legislature by providing that the majority of its Members shall be elective.[x]

The final wording of the above in section was largely due to the presence in Ottawa of H. E. Seelye, a newspaperman who “accompanied the delegates as a special correspondent of the Daily Colonist and in the interest of responsible government.”[xi] Sir Charles Tupper, in his Recollections of Sixty Years, records, as follows, the inclusion of responsible government in the Terms of Union: –

In the terms formulated by British Columbia there was no provision for responsible government; in fact, a clause which was attempted to be inserted by members of the Council was defeated by a majority vote of that body. The late Hon. John Robson, the late Mr. H. E. Seelye, and Mr. DW Higgins held a conference, and decided that in order to secure parliamentary government it would be necessary for one of their number to proceed to Ottawa and inform the Government there that unless responsible government was assured they would oppose the adoption of the terms altogether, and thus delay Confederation.

Mr. Seelye was selected as the delegate. He succeeded in convincing the Dominion Government that his contention that the province was sufficiently advanced to entitle it to representative institutions was correct. When the terms came back, they contain a clause to that effect, and upon those lines the provincial government has ever since been administered.[xii]

British Columbians can well afford to be grateful to Messrs. Robson, Seelye, and Higgins and to Sir John A Macdonald and his cabinet. It should be noted in this connection that Gov. Musgrave asked John Robson to be a member of the delegation, but he refused because he felt he could not leave his business. He was then editor of the Victoria Colonist.[xiii]

During the months which elapsed between the formulation of the final draft of the Terms of Union, in the summer of 1870, and the meeting of the Legislative Council in January, 1871, Her Majesty’s Government had issued the Order in Council of August 9, 1870, whereby the Constitution of the Legislative Council of British Columbia was altered so as to permit that the majority of the members should be elective. Prof. Arthur Barriedale Keith, that eminent authority on constitutional law is therefore legally, though not absolutely historically, correct when he writes: –

“In the case of British Columbia self-government was granted on its entry into the Dominion of Canada, by the creation of a representative Legislature by an Order in Council of August 9, 1870, under the Act 33 and 34 Vict., c 66 and by the local Act No. 147, 1871, and was continued by the instructions to the Lt. Gov. given by the Dominion government….”[xiv]

Of the three representatives sent by British Columbia to Ottawa, Dr. Helmcken had been opposed to Confederation, but Trutch and Dr. Carrall had supported Confederation but not responsible government. After the conclusion of negotiations Trutch went to England, Carrall remained one month in Ottawa and Helmcken and Seelye at once returned to British Columbia.

The next move now lay in the hands of the Dominion Government. The Order in Council, to which reference has already been made, issued at Windsor on May 16, 1871, provided for the incorporation of British Columbia with the Dominion of Canada on the terms set forth in the Addresses from the Parliament of Canada and the Legislative Council of British Columbia. The Queen’s Privy Council for Canada, the Canadian Cabinet, now had to provide for the setting up of the provincial government of British Columbia. The first office to be filled was that of Lt. Gov. Ottawa’s choice fell upon Joseph William Trutch. In his Life of Macdonald, Sir Joseph Pope records the esteem in which Sir John A Macdonald held Trutch: –

Sir John Macdonald considered Sir Joseph Trutch a man of high honour and integrity, whose advice was always dictated by a regard for the public interest.”[xv]

Dr. Helmcken, who knew Trutch well, states in his unpublished memorandum that he considered that Trutch was head and shoulders above them all. This was high praise coming from Dr. Helmcken, whose political experience antedated that of Trutch by several years.

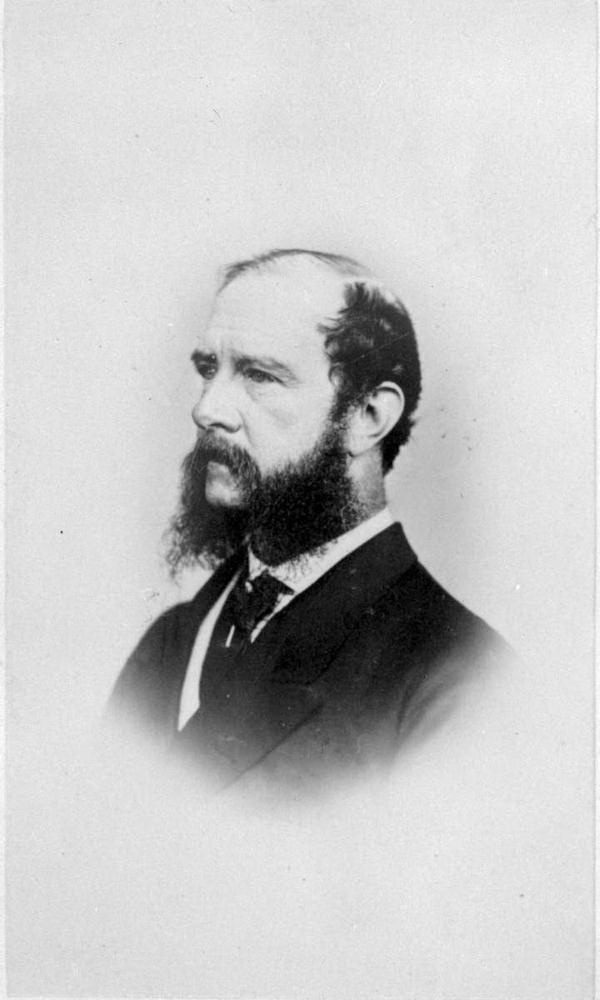

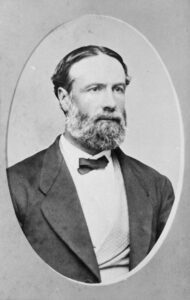

Joseph William Trutch was an Englishman, the son of William Trutch, solicitor, of Ascot, Somerset, and St. Thomas, Jamaica. He trained as a civil engineer and became a Member of the Institute of Civil Engineers. In 1849 he joined in the gold-rush to California, but later returned to the practice of his profession and was for several years employed by the United Government. When in England in 1858 he applied for the position of Surveyor-General of the new colony of British Columbia but was unsuccessful. Next year he came out to British Columbia and for five years built roads and bridges. The Alexandria Bridge at Spuzzum was one of his ventures. In 1864 he was appointed Colonial Surveyor and Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works for British Columbia. This office he held until Confederation. On July 1, 1871, he was gazetted as first Lieutenant Governor of the Province of British Columbia.

Gov. Musgrave remained in British Columbia until after the formal entrance of the new Province into the Dominion. Trutch was on his way out from England but was delayed. Musgrave accordingly left Victoria on July 26, 1871, and Trutch did not arrive until August 13. He was duly sworn in on August 14. During the intervening weeks British Columbia was officially without a government, although, as might be expected, the former colonial officials continued to function. The Victoria Colonist lamented the interregnum but there was really nothing to be done but await the arrival of the Lieutenant Governor.

Trutch was in rather a difficult position. Nearly three thousand miles from Ottawa, with no direct railway communication across Canada, in fact with no railway communication at all north of San Francisco, without money and with few precedents to guide him, he had to create the provincial government of British Columbia. On the whole he proved equal to the task.

Fortunately for Trutch, Sir John A Macdonald was prepared to give him all possible assistance. Among the Macdonald Papers in the Public Archives in Ottawa, Trutch’s letters to the Prime Minister are carefully preserved, and from them and from the letter-books in the Archives of British Columbia it is possible to obtain the Lieutenant-Governor’s own story of his efforts.

The first letter from Trutch to Macdonald introduces Captain Philip Hankin, former Colonial Secretary, and bears the date of August 15, 1871. Hankin was leaving Victoria for Ottawa on his way to England. The gist of the letter is contained in the sentence: “Captain Hankin is desirous to arrange personally with you the Exact amount of Pension to be paid to him and the place and manner of its payment.” Let us hope Hankin received his pension and found it adequate.[xvi]

Two days later on August 17, Trutch dispatch the following enlightening telegram in cipher to Macdonald: –

No funds to meet outstanding debts and current liabilities of local Government. Please telegraph authority to bank to pay half year subsidy in advance, say $100,000.

It was evident that Ottawa was to finance for the first year the cost of provincial government in British Columbia from the subsidies to be provided under the Terms of Union.

In his first lengthy dispatch Sir John a Macdonald, dated Victoria, August 22, 1871, Trutch records that he had been detained for a fortnight in San Francisco awaiting Governor Musgrave’s arrival and had “a protracted trip of eleven days up the coast in the Sparrowhawk.” His reception and Victoria had been cordial, and he had spoken freely as to his “position and intentions” when replying to an address of welcome. Amor De Cosmos, editor of the Victoria Standard, had” not found anything to take exception to” in the Lieutenant-Governor’s program, although he had cautiously abstained from approving it. Trutch also states that he is hurrying on the revision of the voters list and expects to hold the first Provincial elections about the middle of October. The following passage explains his attitude towards the introduction of responsible government:

Until the Election takes place I have determined not to attempt to establish a responsible ministry for the reasons stated in reply to the Civic Address, but as it is absolutely necessary for the Conduct of Public business that there should be an Executive Council I have appointed the Assistant Colonial Secretary, Mr. Good whom you saw at Ottawa and Mr. Pearse, the Surveyor General, Heads of their respective Departments and I have been fortunate enough to get Mr. McCreight the leading barrister here – a gentleman who commands the respect and confidence of the Community to a greater Extent than that of any other member of the profession – although he has hitherto consistently abstained from politics – to act as Attorney General on the clearly express understanding that their appointments are to remain only until the Election when I shall select and appoint a ministry from the Representatives then Elected.[xvii]

The Lieutenant Governor also explains that all customs dues from July 20 had been paid into the Bank of British Columbia “to Dominion Account” and that as no monies had been paid over by the Dominion to the Province he had accordingly found the local treasury nearly empty. For that reason, he had sent his cipher telegram, but having received no reply had arranged for a loan from the bank without interest. The credit of the Dominion of Canada was evidently superior to that of the former colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia. There were occasions when Governor Seymour had to pay 18per cent interest on advances from the Bank of British Columbia! Trutch adds that he had talked over the situation with the Honourable Hector Langevin, who was then visiting the new Province.

A telegram, dated August 28, 1871, brings up a rather important administrative problem. It runs, in part, as follows:

Many of Colonial Office dispatches to Governor Musgrave which I am instructed by Secretary of State for Provinces to send to Ottawa relates (sic) to matters of importance under jurisdiction of local government and in some cases are directed to be laid before legislative counsel – ought I not to retain original if not certified copies or will such copies be returned to me from Ottawa.[xviii]

The Government Gazette of British Columbia, under the date of September 16, 1871, contained Trutch’s proclamation for issuing writs calling the Provincial election. Returning officers were named for two various ridings. A revised list of returning officers was forwarded by Trutch to Macdonald on September 17.

On October 9 the Lieutenant Governor penned a lengthy letter to Sir John A Macdonald. He tells of his inability to persuade Doctor J.S. Helmcken to accept the office of Prime Minister of British Columbia. Doctor Helmcken had announced his intention of retiring from politics and devoting himself to his profession. Trutch was even more doubtful as to whether he would accept a seat in the Canadian Senate. A few weeks later, when the good doctor was offered a senatorship, he refused it. He probably felt that he had done all he could for British Columbia when he went to Ottawa to arrange the terms of Union. Doctor Helmcken really belonged, politically, as did Sir James Douglas, to the Colonial Period. He was to live into the twentieth century – his death occurred in 1920 – but he never again took an active part in politics.

Trutch continued his report to Macdonald on events since his swearing in as Lieutenant Governor:

Since then, as Langevin has probably told you, I have been getting on well enough, but the difficulty of forming a respectable Ministry is yet to come and until that is over I am not in a position to congratulate myself.

However, I think I can manage to get some decent men who take a hand in government – although most of our representatives will be queer kittle cattle, I fear. A wild team to handle no doubt they will be but after kicking and plunging a while they’ll settle into their collars all right, I trust.[xix]

A later passage in this letter clearly shows that Trutch was still in doubt as to his position as Lieutenant Governor. Responsible government was not yet a reality in British Columbia, and he took Macdonald’s advice on the statement of government policy in the speech from the throne:

I wish you would also if you please give me a hint as to how far my speech and opening the House is supposed to express my own opinions or to be simply an Exposition of the policy of my responsible Ministers as I confess I am somewhat puzzled on this point. Of course, I know how this would be in the House of Parliament at home – or at Ottawa, but are we under the same understanding here?[xx]

The question of the defence of the Pacific Coast is next raised. Trutch had been informed that H. M. S. Sparrowhawk is to be recalled. That would leave only the Boxer, a gunboat totally inadequate for the protection of the coast. Trutch’s comments are penetrating:

The Province will be at a great disadvantage – indeed I look upon it that if you cannot get the Imperial Government to continue the Sparrowhawk or send some similar ship in her place you will have to provide a Dominion cruiser for the purpose – and this will involve an annual expenditure of $70-$80,000 I suppose. On the same subject I may remark that you will need one or more revenue cruisers to protect your Customs along the Coast – as well as for the purpose of visiting and keeping the Indians and outlying white settlers in order, if not to suppress entirely the sale of liquor to the tribes along the Coast of Vancouver Island and the N. West of the Mainland.

Declining this most important matter (in which I think Mr. Langevin will coincide) I have today telegraphed to you to the effect that the Sparrowhawk was ordered home and asking you to prevent her leaving B. C. If possible.[xxi]

In his dispatch of November 21, 1871, Trutch reports to Macdonald that he had “established a Responsible Government” and adds that he hoped “soon to be relieved by them from the rather over amount of work” he had had of late.[xxii]

The first cabinet of British Columbia was constituted as follows: J. F. McCreight, Q.C. Premier and Attorney-General; A. Rocke Robertson, Q.C., Provincial Secretary; Henry Holbrook, Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works, President of the Council.

The Lieutenant Governor thus comments upon his selection of ministers of state:

Langevin very well knows the gentleman whom I called upon to form a Ministry – Mr. McCreight – and I am sure you will agree with me he was a man of all this Province for the post and that his selection of Mr. Robertson as Colonial Secretary is also unexceptionable. The other Member of the government is yet appointed. Mr. Holbrook is only holding the office of Lands and Works temporarily until the Cariboo Election returns are received when a Member from that important district is to be substituted for him.[xxiii]

With the creation of the first ministry, responsible government was legally introduced into British Columbia. But it was far from being responsible government in the fullest sense of the term. Lieutenant Governor Trutch was still in control of the government and he remained so during the whole of the McCreight regime. Space forbids a full discussion of this important topic. Trutch realized he was conducting an experiment in popular government and leaned heavily upon Ottawa. The concluding sentence of his dispatch makes this clear:

I am so inexperienced and indeed we all are in this Province in the practice of Responsible Government which we are initiating that I step as carefully and guardedly as I can – and whilst teaching others I feel constantly my own extreme need of instruction on this subject which must account to you – if you please – for the trouble which I have put you to – in which I know ought not to have been imposed on you.[xxiv]

Writing over forty years later R. E. Gosnell reviewed the introduction of responsible government by Trutch in the following penetrating passage:

During the McCreight regime Joseph Trutch as Lieutenant Governor, sat in the Executive Council, and discuss all matters submitted with the members. He was the dominating influence on the cabinet, so that it might be said that he was not only the Throne itself, but the power behind the Throne. He was a man of more than ordinary ability, who combined professional knowledge with practical business experience and capacity. From his former connection with the Government as chief commissioner of lands and works, he was familiar with all the details of government machinery. He had also a particularly practical mind and possess a sound and evenly balanced judgement. To the members of his administration’s advice and assistance were of great service.[xxv]

In the transition period from colony to province in the setting up of the machinery of responsible government Joseph William Trutch played a useful part. In the colonial period down to 1871 responsible government did not exist. The Confederation Debate made it clear that the official members, following the lead of Governor Musgrave, were unwilling to include responsible government is one of the terms of union. John Robson and T. B. Humphreys strove for its inclusion, but even Amor De Cosmos, that champion a popular rights, gave at the time only a qualified support. The Dominion Government was unwilling to have responsible government set up in the Province of British Columbia after Federation. It felt to the task of Lieutenant Governor Trutch to set up and put in motion the machinery whereby the new Province obtained responsible government. Nonetheless sometime had to elapse before the elected representatives of the people of British Columbia had full control over provincial affairs. Even in 1871 the political education of British Colombians was far from complete.

M. Sage

University of British Columbia,

Vancouver BC.

[i] “And whereas Her Majesty has sought fit to approve of the said terms and conditions (of Union) it is hereby ordered and declared by Her Majesty, by and with the advice of Her Privy Council, in pursuance and exercise of the powers invested in Her Majesty by the said Act of Parliament the British North America act, 30 and 31 Victoria, Cap, 3.), That from and after the 20th day of July, one thousand eight hundred and seventy-one, the said Colony of British Columbia shall be admitted into and become part of the Dominion of Canada, upon the terms and conditions set forth in the hearinbefore recited Addresses.” The full text of this order in council is given in the Revised Statutes of British Columbia, 1871, Appendix, pp 193 – 216.

[ii] British Columbia. Legislative Council. Debate on the subject of confederation with Canada, Victoria, 1870, pp 91 – 124.. Reprint, Victoria, 1912, pp. 195 – 128. The page citations which follow are from the 1912 reprint.

[iii] Ibid, p 97

[iv] Ibid, p 98

[v] ibid., p 101.

[vi] ibid., P. 103

[vii] Journals of the Legislative Council of British Columbia…. 1870, Victoria, p. 4. The of Oregon, California and Washington Territory had at that time representative but not responsible government.

[viii] Debate on Confederation, 1912 Reprint, p 109.

[ix] ibid., p 116.

[x] Journals of the Legislative Council of British Columbia, Session 1871, Victoria, 1871 pp 5 – 6.

[xi] Howay, F.W. , and Scholefield, E,O,S., British Columbia, Vancouver, 1914, II., p 293.

[xii] Tupper, Sir Charles, Recollections of 60 Years in Canada, London, 1914, pp 127 – 28.

[xiii] See the article entitled “Personal – Historical” in the British Columbian, July 8, 1882.

[xiv] Keith, A. B., Responsible Government in the Dominions, Oxford, 1912, I, P. 24.

[xv] Poke, Sir Joseph, Memoirs of Sir John Alexander McDonald, Toronto, 1930, P. 505 n.

[xvi] Macdonald Papers, Public Archives Ottawa, Ottawa. The correspondence has been bound, and one volume is entitled, Letters from Lieutenant Governor Trutch, Victoria, BC, 1871 – 1873. The citations which follow are all taken from the same volume.

[xvii] Trutch to Macdonald, August 22, 1871, McDonald Papers, Trutch Correspondence 1871 – 73, pp 14 – 16.

[xviii] ibid., p 30

[xix] ibid., pp 53-54. The italics are Trutch’s

[xx] ibid., pp 58 – 59. Here Trutch is rather prematurely getting close to the crux of the question.

[xxi] ibid., pp 68 – 70.

[xxii] ibid., p 98

[xxiii] Macdonald Papers, Trutch Correspondence 1871 – 73, pp 98 – 99

[xxiv] ibid., pp 101 – 102.

[xxv] Scholefield, E.O.S, and Gosnell, R. E., British Columbia, 60 Years of Progress, Vancouver and Victoria, 1913, Pt. II p 15, n I. Trutch not only sat on the executive Council but presided at the meetings.