AMOR DE COSMOS, JOURNALIST AND POLITICIAN.*

THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, WALTER N. SAGE. VANCOUVER, B.C.

BRITISH COLUMBIA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY, Vol VIII, No. 3, July 1944

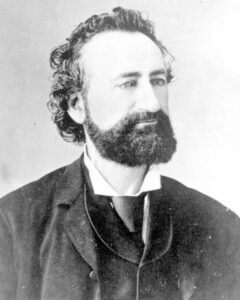

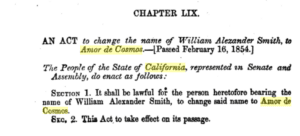

The second premier of the Province of British Columbia was Amor De Cosmos, that most colourful figure in our early political history. Born as William Alexander Smith in Windsor, Nova Scotia, in 1825, he changed his name by Act of the California Legislature in 1854. His death occurred at Victoria, B.C., in 1897. He never married, and his new name died with him.

The second premier of the Province of British Columbia was Amor De Cosmos, that most colourful figure in our early political history. Born as William Alexander Smith in Windsor, Nova Scotia, in 1825, he changed his name by Act of the California Legislature in 1854. His death occurred at Victoria, B.C., in 1897. He never married, and his new name died with him.

De Cosmos was a journalist by profession and a politician by temperament. He arrived in Victoria during the hectic days of the gold-rush to Fraser River and on December 11, 1858, issued the first number of the British Colonist. He did not approve of the policies of Governor Douglas, whose actions, he claimed, were shrouded in a “wily diplomacy.”[1] To him Douglas “was not equal to the occasion.” Douglas, on his part, did not greatly approve of De Cosmos. This was natural enough, since temperamentally they were poles apart. The Nova Scotian wished to play the role of reformer, inspired perhaps by the precepts and example of Joseph Howe.[2] He became an active opponent of what he termed the Family-Company-Compact, but at first made, little headway. Later he was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Vancouver Island and supported the Union of 1866. He championed the cause of Confederation and took a prominent part in the memorable debate in the Legislative Council of British Columbia in March 1870. Governor Musgrave did not select him, however, as one of the delegates sent to Ottawa to arrange the terms of Union. De Cosmos sat in the first Legislative Assembly of British Columbia and was also elected to the House of Commons in Ottawa. In 1872 he succeeded John Foster McCreight as premier of British Columbia, but less than two years later, when dual representation was abolished, he preferred Ottawa to Victoria and resigned the premiership. He continued to represent British Columbia at Ottawa until his defeat in the election of 1882. His later years were spent in retirement at Victoria.

In the Archives of British Columbia may be found a brief account of the early life of Amor De Cosmos. It was written by his elder brother, Charles McKeivers Smith, and from it the late Beaumont Boggs, of Victoria, seems to have derived much of the information regarding De Cosmos’s early life for his paper “What I remember of Hon. Amor De Cosmos,” delivered before the British Columbia Historical Association at its meeting on May 3, 1929.[3] Since so little is known about De Cosmos before his arrival in British Columbia it is well to quote this valuable primary source in full:

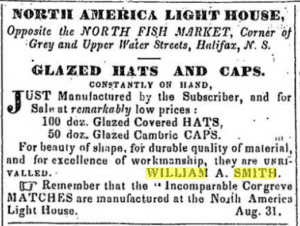

“Hon. Amor de Cosmos was born in Windsor Hants County Nova Scotia on the 20th of August 1825. His education began in a private school and from it he passed into the Windsor Academy and during the time he was there made rapid progress in his studies until he was about 14 years of age, when his parents moved to Halifax and took him with them. Shortly after his arrival in that city secured a clerkship in the old and well-known wholesale and retail grocery and liquor house of William and Charles Whitham, in whose employ he remained for some ten or eleven years. During that time, he attended the grammar school of John S. Thompson, father of the late premier of the Dominion and was also a member of the Dalhousie College Debating Club in which nearly all the political matters of the colony were debated, which doubtless was of great service to him in after years.

When the California gold excitement was at its height in 1851 he like many other men being anxious to better his condition decided to seek his fortune in the Eldorado of the west. On leaving his home at Halifax went to New York and from there crossed the continent to St. Louis on the Missouri River, at that time on the very outskirts of civilization. There he joined a party who were leaving for California, but on account of Indian troubles and other obstructions on the way were obliged to remain at Salt Lake for the winter as they were too late to cross the Sierra Nevada mountains. In the spring of 1853 the party continued their journey on to California, and after some four or five days of slow traveling along the trail, he decided to go on alone, as he had a good horse and could travel much faster than the party he was with. Having provided himself with plenty of food and ammunition for his rifle and pistol, he left the train and by fast traveling soon reached the Humbolt Valley and followed the river down until he came to the crossing then following the trail until he came to where it branched off into Northern California. When he reached that point he and his horse were suffering terribly from drinking alkali water, as he was not able to find any other, however he pushed on as rapidly as possible and soon found fresh water which revived him and his [horse] and in a few days, he arrived in Placerville Eldorado County in June 1853. Three weeks later the train came there, having his Camera and Daguerreotype stock in it which he brought across the plains. He at once set up his Camera and commenced to take views of mining claims with the owners on them, he being the first in that business it proved a very profitable speculation much better than mining. His success in taking views of mining, claims induced him to continue the business through all the mining camps in the country from the Yuba River in the north to Jacksonville on the Tuolumne River south near the Mexican boundary line which enabled him to obtain and [sic] excellent view of all the mines [in the] great valley and was above a splendid paying speculation as well. On his return from the southern mines [he] settled down in the town of Orville, Bute County, and was engaged in mining speculations and business of other kinds up to the time of the Fraser River gold discovery, when he decided to visit Vancouver Island see the country, investigate the gold mines reports and any other matters that might interest him. In order to carry out his desire took passage on board the steamer Brother Jonathan and arrived in Victoria on May 16th, 1858, w[h]ere he remained for several days, and being satisfied from what he had seen and heard of the country and mines returned to California settled up his business there and came back to Victoria in the latter part of June in which place he made his home up to the time of his death.[4]

Some further particulars of De Cosmos’s family and early years were secured by Dr. B. C. Harvey, Archivist of Nova Scotia, in 1933. Dr. Harvey discovered that one of De Cosmos’s sisters, Mrs. Peter Hudson Le Noir, was still living in Halifax. She was then in her hundredth year. Writing to Dr. R. L. Reid, at whose request the search for information regarding De Cosmos had been made, Dr. Harvey reported as follows:

“ I arranged an interview, and though I found her hearing very good she suffers from the usual confusing of ideas, and has a tendency to wander from her brother to her husband and her son, all of whom are dead. I found it very difficult, therefore, to get any definite information, though I went like a reporter with specific questions, and kept repeating my questions at intervals for confirmation.

It seems that the paternal grandfather was Joseph Smith who settled in Newport. I cannot find such a man getting a land grant under the Loyalists, although I found three Joseph Smiths, one of whom first settled at Shelburne. He may have drifted to Newport.

The maternal grandfather was Daniel Weems or Wemyss, apparently a Haligonian. Jesse Smith, son of Joseph, married Charlotte Weems or Wemyss, daughter of Daniel, and they had ten children, Daniel, Charles, William Alexander, Jesse, John, Charlotte, Sarah Louise, Mary Ann, Frances Sophia, and Jessie. Charlotte and William Alexander are the two who went to British Columbia finally. Jesse Smith lived first in Windsor, and then in Halifax. William Alexander went to King’s Academy, where he, according to Mrs. Le Noir, was very bright. One day the teacher called his father in and said, “You better take him home; instead of me learning him he’s learning me.”

Mrs. Le Noir confirmed Boggs’ memories that William Alexander worked in a shop in Halifax, and at the same time went to night school and took part in debating. She thought that he just took up photography, and she had no memory of his working with a professional. I quizzed her on his relationship with Howe, and she said he was a great admirer of Howe and tremendously interested in politics, and ready to fight for Howe.[5] While in California, as has been noted, William Alexander Smith changed his name to Amor De Cosmos. The reason usually given is that he wished to avoid confusion at the post-office. Mr. A. G. Harvey, of Vancouver, B.C., has gone fully into this problem of the change of name and it is only necessary to note that Smith employed three languages to create his new and rather high-sounding appellation.[6] In June 1858, De Cosmos returned to Victoria and settled there. He did not at first embark upon a journalistic career and it may be hazarded that he was either “engaged in mining (speculations” or was supporting himself by photography. Unfortunately, there is no evidence on this subject, except by inference from his brother’s account. At this time the Victoria Gazette had the journalistic field to itself. The Gazette was founded in June 1858, by experienced newspaper-men from California. It had sound financial backing and formed a strong link with California.

According to a statement made by De Cosmos in 1883, he started the British Colonist “for amusement during the winter of 1858—9.” De Cosmos’s rival, David W. Higgins, had claimed that De Cosmos began the Colonist as an opposition paper, and the doughty Amor refuted the charge as follows:

The statement that the Colonist was started as an opposition paper is strictly untrue. It was started for amusement during the winter of 1858—9; but circumstances afterwards changed it into an established political journal.[7]

It should, however, be remembered that De Cosmos wrote this article soon after he had retired from politics, and that his statements are not altogether borne out by a careful perusal of the early numbers of the Colonist. His attacks upon Governor Douglas, as has been noted, began in the first issue of the paper.[8]

At first the Colonist had an up-hill fight against the more popular Gazette. De Cosmos concentrated on local issues and politics and his opposition to Governor Douglas gave him a certain following, especially when the Governor in April 1859, tried, unsuccessfully, to suppress the Colonist. The Gazette, as a rule, avoided discussion of Vancouver Island politics. In July 1859, the San Juan question came to a head and anti-American feeling waxed strong in Victoria. The Gazette felt the effects of this change in public sentiment and in November it suspended publication. This left the field open to De Cosmos and his Colonist, and he and his paper may be said to have ruled the journalistic roost relatively undisturbed until D. W. Higgins with whom De Cosmos had a lengthy feud) founded the Chronicle in 1862.[9] De Cosmos remained editor and publisher of the British Colonist until 1863. During the intervening years he had taken a rather active part in politics. Defeated on a technicality in the elections of 1860, he was elected a member of the Legislative Assembly of Vancouver Island in 1863.[10] When he was running for office in 1863 De Cosmos set forth a comprehensive platform: responsible government, the union of the colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia, the transfer of the Crown lands to the colony, free land grants to settlers, investigation into the claims of the Hudson’s Bay Company to the townsite of Victoria, free non-sectarian education, reciprocity with the United States, the maintenance of the free port of Victoria, increased representation in the Assembly, and new electoral districts.

It may well be questioned why De Cosmos was unable to carry out his programme of reforms. One reason was that the Family-Company-Compact was too strong, and that public feeling was apathetic. Another was that De Cosmos, in spite of his brilliance, lacked the qualities necessary for a real “tribune of the people.”

Soon after De Cosmos was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Vancouver Island, Sir James Douglas retired from the governorship of both colonies. Separate Governors were appointed, Arthur Edward Kennedy for Vancouver Island and Frederick Seymour for British Columbia. De Cosmos had favoured the union of the two colonies as far back as 1859 and in 1865 championed that cause at the polls.

But the Union of 1866 did not provide the hoped-for solution of the constitutional and financial difficulties of British Columbia. De Cosmos now came forward as a champion of Confederation, and in 1867 introduced into the Legislative Council of British Columbia a resolution requesting Governor Seymour “To take such steps without delay, as may be deemed by him adapted to insure the admission of British Columbia on fair and equitable terms, this Council being confident that in advising this step they are expressing the views of the Colonists generally.”[11]

Governor Seymour was half-hearted in his inquiries and delayed till September 24, 1867, the sending of a dispatch in reference to his telegram of March 17 inquiring whether provision could be made in the Bill before the British Parliament for the ultimate admission of British Columbia into the Dominion of Canada. By his policy of Council delay Seymour shelved the question.[12] By 1868 the Legislative was anti-confederationist and an annexation movement had come into existence in British Columbia.

De Cosmos visited Eastern Canada in the summer of 1867, and in August spoke at the Canadian Reform Convention on the twin subjects of Confederation and reform. He advocated the entrance of the Pacific colony into the new Dominion. On his return to Victoria he was chagrined to find that the Confederation movement had been blocked by the masterly inactivity of the Governor. During the winter he kept up the struggle for Confederation by writing letters to the British Colonist.

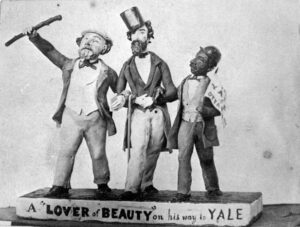

By the spring of 1868 it was evident that the people of British Columbia were strongly supporting Confederation but that Governor Seymour and his officials along with a small group of annexationists opposed it. The Confederationists, however, were not idle. On January 28, 1868, a public meeting in Victoria had drawn up and adopted a lengthy memorial favouring federation with Canada. A copy of this memorial reached Ottawa in March and drew a favourable reply from the Canadian Government. Seymour still pursued his policy of delay, and a majority in the Legislative Council supported the Governor in his opposition to federation. De Cosmos, on April 24, 1868, moved, and Captain Edward Stamp seconded, an address to Queen Victoria favouring Confederation and setting out provisional terms. This motion was lost, and an amendment was carried by the official majority which agreed with the general principle of union with Canada but counselled delay.[13] Seymour had apparently won the day. De Cosmos, however, would not accept defeat. In association with John Robson, Dr. I. W. Powell, Dr. R. W. W. Carrall, J. Spencer Thompson, and others, he carried the fight to the people. A Confederation League was formed in May 1868, in Victoria and branches were organized on the mainland. In September 1868, the league held a convention at Yale, which passed resolutions in favour of federation and outlined terms of union. Although denounced by the anti-confederationists of Victoria, the Yale convention did its work well. It was in its way the British Columbia counterpart of the Charlottetown and Quebec conferences. In November 1868, an election was held for the “popular” members for Victoria in the Legislative Council. By means of a political trick the Government party and the annexationists won. All residents of Victoria, including aliens, Indians, and Chinese, were permitted to vote. De Cosmos was defeated, but it was a pyrrhic victory.

The Legislative Council on February 17, 1869, again went on record as opposing federation. The resolution was quite definite:

“That this Council, impressed with the conviction that under existing circumstances the Confederation of this Colony with the Dominion of Canada would be undesirable, even if practicable, urge Her Majesty’s Government not to take any decisive steps toward the present consummation of such Union.[14]

This resolution was the high-water mark of the anti-confederationist cause in British Columbia. Governor Seymour’s sudden death in June 1869, deprived the governmental group of their leader and in spite of their renewed activities in the autumn of that year the annexationists were unable to secure the support of more than a small fraction of the inhabitants of British Columbia.

The new Governor, Anthony Musgrave, was sent to British Columbia to secure the passing of the legislation necessary for the admission of the Pacific Coast colony. Both the British and the Canadian Governments were by now anxious to have the question decided, especially since the proposed cession of the Hudson’s Bay territory was expected to remove one of the chief causes for delay. Musgrave did his work well and the Legislative Council which had hitherto opposed federation now swung round to its favour.

Late in 1869, Dr. Davie, one of the elected members of the Council for the Victoria District, died and, in spite of the opposition of the Colonist, now controlled by his rival, David W. Higgins, De Cosmos was triumphantly elected to fill the vacancy. He was, therefore, present to take part in the momentous debate on Confederation which occurred in March 1870.[15]De Cosmos had long been a supporter of union with Canada and in this debate, he felt himself free to criticize those officials who had formerly strongly opposed but who now were equally enthusiastic for Confederation. He congratulated the House on its noble work of nation-building, and reiterated his faith in the “grand consolidation of the British Empire in North America.” That this faith was of long standing was evident from his statement that “From the time he first mastered the institutes of physical and political geography he could see Vancouver Island on the Pacific from his home on the Atlantic.” He added the following significant passage:

Sir, my political course has been unlike that of most others in this Colony. Allow me to illustrate my meaning by the use of another old adage. My course has been that of ‘beating the bush whilst others caught the bird.’ My allegiance has been to principle, and the only reward I have asked or sought has been to see sound political principles in operation. Therefore, Sir, I say again that I congratulate you and this Honourable House on the noble work on which we are all engaged.’[16]

In concluding his speech De Cosmos stated that he favoured Confederation “provided that the financial terms are right in amount and if the other terms will contribute to the advancement and protection of our industry.”[17]

In the later stages of the Confederation debate, John Robson and De Cosmos fought for the inclusion of responsible government in the Terms of Union, but Governor Musgrave and the officials were not ready to accept the proposal. Robson moved:

“ That a humble address be presented to His Excellency the Governor recommending that a Constitution based on the principle of Responsible Government, as existing in the Province of Ontario, may be conferred upon this Colony, coincident with its admission into the Dominion of Canada.’[18] De Cosmos declared in favour of “representative institutions and Responsible Government, irrespective of Confederation” and threatened if responsible government were not included to leave the Council and go to his constituents.

When Governor Musgrave selected the three delegates to be sent to Ottawa from British Columbia to arrange the final Terms of Union he did not include Amor De Cosmos. John Robson was asked to go to Ottawa but refused on account of his newspaper work. He was then editing the Victoria British Colonist. De Cosmos had now re-entered the newspaper field as editor and proprietor of the Victoria Daily Standard. Although Robson and De Cosmos were both supporters of Confederation and of responsible government they were by no means friends. Their editorial combats in the Victoria press were no mere shadow fights. It was a war to the knife between two able and ambitious men.

To Lieutenant-Governor Joseph William Trutch, who succeeded Musgrave, fell the task of choosing the first Provincial ministry of British Columbia. Trutch had been formerly Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works in the colonial administration and was, therefore, well acquainted with the political situation in the new Province. He chose John Foster McCreight as first Premier of the Province. Neither Amor De Cosmos nor John Robson was included in McCreight’s cabinet. In a letter to Sir John A. Macdonald, dated Victoria, B.C., November 21, 1871, Trutch thus comments: “The Newspapers however are rampant because no office has been provided for either of the editors,” but adds: “As for the Newspapers if the Govt. want the support of either of them I dare say they can obtain it.”[19]

De Cosmos was elected as a member for Victoria District in the first Legislative Assembly of British Columbia. He was also elected as Member of Parliament for Victoria in the first Federal election held after British Columbia became a Province of the Dominion of Canada. At that time dual representation was allowed. It was later to be abolished. Lieutenant-Governor Trutch was of opinion that the people of British Columbia had “now got the best cabinet that can be formed out of the present House,”[20] but De Cosmos did not agree with him. As early as November 1871, De Cosmos had exhorted the Liberals of the Province:

“To rally round their old leaders—the men who have year after year fought their battles and have in no instance deserted the popular cause. To take any other course is to convict themselves of Treason to manhood, Treason to the Liberal party, that year by year for fourteen years have urged Responsible Government, Union of the Provinces, and Confederation with the Dominion. It is no Treason, no public wrong to ignore the nominees of Governor Trutch. [21]

John Robson and D. W. Higgins, who had been on the whole opposed to McCreight, began in January 1872, to veer round towards the administration. De Cosmos lost no time in attacking the Colonist “as chief trumpeter to sound the praises of the Legal Trio who have thoughtfully divided between them the only three Cabinet offices of emolument which Gov. Trutch at present has it in his power to bestow.” [22]

The Colonist was not slow in answering De Cosmos’s challenge. In a long editorial entitled “Party Government and Patriotic Journalism,” it upheld the McCreight administration and attacked De Cosmos as “utterly devoid of political principle and consistency.” The following extract is illuminating:

“To put the whole issue between our local contemporary and ourselves in the plainest light the editor of the former has conceived the idea that he ought to have been selected as the first Premier of the Pacific Province under the new dispensation; and that he has turned upon us, and abuses us and misrepresents us in his usual happy style, because we will not assist in placing him in that position,—accusing us as is his custom, of all sorts of interested motives, he alone being the pattern of unselfish devotion! Although the reasons which have led this journal to take the position of an independent supporter or opposer, as the case may be, of the present Ministry, have already been stated, let us put the case as curtly as possible. It is extremely questionable whether the country would be better satisfied to see Mr. De ‘Cosmos occupying the position of Premier. But, even assuming that it would have preferred him, to make the change now would be virtually to postpone all legislation till next winter, and we feel certain that the country is not prepared to accept the change at such a price.[23]

De Cosmos lost no time in taking up the Colonist’s challenge. He claimed that the McCreight ministry were “nominees of the Crown, — almost self-elected, — not the choice of the majority,— not the leaders of the majority,—not appointed after the consent of the majority had been obtained,—and besides were not the men who had been battling for the rights and advancement of the people in any one particular.”[24] In another editorial he denounced McCreight and his fellow ministers as having “not one solitary, legitimate claim on the country.”

“They never spent an hour’s toil, never a dollar of their money, — never opposed the enemies of Union, Confederation, Representative Institutions, or Responsible Government. But when the battle was over, the victory won, and the spoil to be divided then they came forward as the purest patriots, to greedily devour what better, more honorable, and much more patriotic men produced by years of toilsome labor in behalf of their country.[25] The Colonist retorted with an attack on De Cosmos as the head of the Meites. It also pointed out that by seeking and obtaining a seat in the Federal house, when he was already sitting in the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia, De Cosmos was thereby depriving the Pacific Province of its full representation at Ottawa. In a spirited editorial on January 26, Robson poured the vials of his wrath on De Cosmos as follows:

“There is one among us who for many years past has been talking patriotism and vaunting self-denial and love of country—the great ME of British Columbian Politics, the great promoter (in his own estimation and for his own ends) of Confederation, one who should be a great warrior for the Dominion. Where is he? Of course, at Ottawa, or on his way there. Not he! The soldiers, the quiet, modest unprofessing, are all wending their way to the battlefield, or are about to do so; but he, the great De Cosmos, the Falstaff of the Pacific, is waiting here for more sack![26]

When at length De Cosmos did leave for Ottawa in February 1872, the Colonist speeded the departing legislator with a satirical attack entitled “Exit, Humbug “:

“He turns his back upon the Local Legislature ere, yet it has been a week in session and before a single public measure has come up! Nay, he runs away at the very moment the tariff question is on the notice-paper—the very question upon which he gained his election and fooled the farmers.[27]

In contrast to the above rather lurid passage may be cited the following statement which appeared in the Daily Standard on February 17, 1872, setting forth De Cosmos’s reasons for leaving for Ottawa:

“As very important matters will come before the Dominion Parliament in which this province has a deep interest, it was of great moment that Mr. De Cosmos should be early at his post, to make himself thoroughly acquainted with all their details, and thereby be the better prepared to discharge the high and responsible duties devolving upon him.

At Ottawa the last session of the First Parliament of Canada was duly opened on April 11, 1872. Eight new members took their seats, of whom six were from British Columbia. In the record Amor De Cosmos is listed as coming from British Columbia, but the other five as sitting for specific ridings in the new Province.[28] De Cosmos delivered his maiden speech on April 19, in the debate on the Hon. Joseph Howe’s motion that a sum of $45,000 be paid annually for five years to defray the expenses of the Geological Survey of Canada. He praised the work already done in British Columbia, and called attention to the policy adopted in California and Oregon “where men of the highest attainments were engaged in what was termed economic geology, the results being most beneficial, and hoped that in any directions or instructions given to the gentlemen who might be chosen in Canada, they should be asked to attend particularly to that branch.”[29] It is probably rather typical of De Cosmos that as early as 1872 he should have already grasped the importance of economic geology.

De Cosmos spoke again three days later in a debate on the protection of agricultural interests. He stated that “the feeling of British Columbia was a unit in favor of the protection of agricultural industry.”[30] The fact that British Columbia had accepted the Canadian tariff should not be interpreted to mean that the Pacific Province “was not in favor of protection on agricultural interests.” “The farmers of British Columbia,” he added, “were comparatively poor and the country rugged and they could not compete with America without protection.”

On May 1, 1872, De Cosmos spoke in support of a motion by T. Oliver, M.P. for Oxford North, Ontario, asking for “the correspondence relating to fees charged by American officials on goods and produce passing through the United States in bond.”[31] He pointed out that “the question was one in which British Columbia was specially interested, as they imported largely from Great Britain via San Francisco and Panama.” He also stated that “the pack trade along the frontier was at times compelled to cross the border, when they had to crave indulgence and assistance from the Custom House officers, often causing great expense.”[32]

In the debates on the Canadian Pacific Railway which took place on May 7 and May 28, 1872, Amor De Cosmos spoke on behalf of Esquimalt and not a port on Burrard Inlet as the terminus of the proposed line. He stated that one of the British Columbian delegates to Ottawa on his return had maintained “that the Pacific Ocean, referred to in the Terms of Union, meant the Pacific above and west of Vancouver’s Island.”[33] He was strongly opposed by Crowell Wilson, M.P. for East Middlesex, Ontario, who championed the Burrard Inlet route. Hon. H. H. Langevin stated that “the intention of the Government was to go to Esquimalt; but of course, if it was impracticable they could not go, and should the railway be carried to Burrard’s Inlet, a ferry will be established, and a line will be carried to Esquimalt as part of the railway.”[34] De Cosmos expressed himself as perfectly satisfied with the explanation made.

In the long debate on the Treaty of Washington, the so-called Treaty Bill, which lasted from May 8 to May 16, 1872, Amor De Cosmos took no part, but his colleagues Wallace and Thompson spoke briefly in support of the Government. Wallace stated that the Treaty “gave a free market for the fish and oil, the trade in which was now carried on at a loss” and claimed that “the ratification of the Treaty would open up the maritime trade and produce the most beneficial results.”[35] J. S. Thompson, M.P. for Cariboo, on May 16 “thought too much time had already been wasted in discussing the Treaty,” but was of opinion that “the Treaty was not all they could expect, but he thought it would be madness to reject it.” [36]The second reading of the Bill was passed on May 16 by a vote of 121 to 55. De Cosmos and the other British Columbia members voted for the Government and with the majority.

On June 3, 1872, occurred a sharp debate on the subject of the salaries of Judges and Stipendiary Magistrates in Quebec, Nova Scotia, Manitoba, and British Columbia. Hon. Edward Blake objected to the appointment of six Stipendiary Magistrates for 10,000 people in British Columbia, and especially to their payment by the Dominion Government. Sir John A. Macdonald explained that the Stipendiary Magistrates had been appointed by the British Government and that they performed the functions of County Court Judges. De Cosmos added that these Stipendiary Magistrates acted as Gold Commissioners, ordinary Magistrates, and also as Justices of the Peace, “and that there was a very general feeling throughout the country against nonprofessional men acting as County Court Judges.”[37] Macdonald, questioned by Blake, replied that when the Gold Commissioners acted as County Court Judges they were paid by the Dominion. This was in accordance with the Terms of Union, whereby “all these gentlemen must be employed or pensioned at two-thirds salary.”[38] David Mills, M.P. for Bothwell, Ontario, objected to “Six Stipendiary Magistrates and three Superior Court Judges to a population of 10,000.” Sir John pointed out that the “salaries were the same as before the Union, and were fixed by the Imperial Government.” The population, he claimed, “was nearer 60,000 than 10,000.”[39] Replying to a charge that since Nova Scotia had no County Courts, their extension to British Columbia had come too soon, De Cosmos stated, “that for a long time British Columbia had had County Courts, and the large space of territory and scattered population necessitated the appointment of six stipendiary magistrates.”[40] After further debate the resolution passed.

The vexed problem of dual representation occupied much of the attention of the Canadian Parliament during this session. J. Costigan, M.P. (Victoria Co., New Brunswick) on April 23, 1872, introduced a “Bill to compel Members of the Local Parliament when dual representation is not allowed to resign their seats before becoming Members of this House.” [41] On May 27 Costigan moved the second reading of the Bill, and F. Geoffrion, M.P. (Vercheres, Quebec) moved in amendment that the Bill be read that day three months.”[42] In the division which followed Geoffrion’s amendment was lost, 65 to 39. De Cosmos voted with the minority. Sir John A. Macdonald did not vote, but when questioned answered much to the amusement of the House that “he had paired with Sir George Cartier,” who, incidentally, had voted against the amendment.[43] A lengthy debate on this question took place on June 3, and a wordy battle ensued between Edward Blake, Sir John A. Macdonald, Sir George Cartier, Alexander MacKenzie, and others as to whether or not Ontario members were affected by the proposed Bill. On division the Bill passed its third reading by a vote of 70 to 36, but Edward Blake reiterated a former statement “that the bill just passed would not prevent Members of the House of Commons from, sitting in the Local Legislatures.” [44]

De Cosmos, apparently, took no part in the debate and since the final division list is not recorded in the Parliamentary debates, it is not certain how he voted. It may, however, be inferred that he opposed Costigan’s Bill. The Legislature of British Columbia had not yet passed legislation barring its local members from sitting in the House of Commons, but as we have seen, the issue was by no means dead.

The First Parliament of Canada was prorogued on June 14, 1872, and general elections were held during the summer. De Cosmos was re-elected with a reduced majority for Victoria, B.C. He returned from Ottawa in August in time to take part in the election campaign, but spent part of his time campaigning for Hon. Francis Hincks in the Nanaimo riding. Feeling against dual representation was strong in Victoria, and that may account for the reduction in De Cosmos’s majority.

The McCreight administration in the meantime had weathered the gales of its first legislative session and all was now fairly quiet on the provincial political front. None the less a storm was brewing. John Robson had withdrawn his allegiance from McCreight and had gone over to the opposition.[45] The Legislature was summoned for October 11, 1872, but the date was later changed to December 17. McCreight’s government had remained in office not so much on account of its strength but because the opposition had been unwilling to force the issue. But by December 1872, it was evident that a trial of strength was fast approaching. The second session of the First Legislature of the Province of British Columbia was duly opened on December 17, 1872. Lieutenant-Governor Joseph W. Trutch in the Speech from the Throne flung down the gauntlet to the opposition in the following paragraph:

I congratulate you on the fact, that far from the prognostications of the failure of Responsible Government in this Province, which were indulged in at the time of the Union, having been verified, the administration of public affairs has been in the main satisfactory to the people in general.[46]

The next day two supporters of the McCreight administration, Messrs. Simeon Duck and Barnston, moved in reply to the Address from the Throne a resolution which contained an expression of pleasure that the Lieutenant-Governor had made the above statement regarding the success of responsible government. The opposition was not slow in taking up the challenge. On December 19, Thomas Basil Humphreys moved and Arthur Bunster seconded a substitute motion:

“Whilst entertaining the fullest confidence in that form of administration known as Responsible Government, still we believe that the administration of public affairs has not been satisfactory to the people in general.[47]

The amendment was carried by one vote, 11 to 10. Two members of the House were absent, Mara and Semlin. If they had been present and had supported McCreight the Government might have been sustained. McCreight resigned on December 20, and Trutch called upon Amor De Cosmos to form an administration. In this connection it is interesting to quote the following comment by R. E. Gosnell taken from his article on Amor De Cosmos:[48]

“The man who succeeded him (McCreight] was [as] unlike him in temperament, in mental calibre, in moral outlook, in training and accomplishments as any man could very well be. McCreight was direct in action and frankly outspoken. Amor De Cosmos was indirect in action and canny of speech when it came to revealing his true mind. If language was ever given to a man to conceal his thoughts it was certainly given to De Cosmos. If McCreight were challenged or provoked to a fight he would fight—fight after the fashion of an Irish gentleman—but fight to a finish. De Cosmos would suffer physical punishment from an opponent without hitting back, but he would lash out with tongue and pen. His predecessor would impulsively forget and forgive; he never. McCreight was bred in an atmosphere of the public schools of the Old Country and Inns of Court. De Cosmos was educated largely in the School of Hard Knocks. Going early to California and to the Western States and afterward to British Columbia, mingling in a society that was not always too polite about words or actions, he acquired that spirit of worldliness and shrewdness that qualified him for the rough and tumble of politics. McCreight was painfully conscientious and scrupulous. De Cosmos had none of such scrupulosities and his political policies were dictated by considerations which were unmoral if need be.

De Cosmos became Premier and President of the Council with George A. Walkem as Attorney-General, Robert Beaven as Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works, John Ash as Provincial Secretary, and W. J. Armstrong, Minister without portfolio. In February 1873, Armstrong became Minister of Finance and Agriculture. Walkem had been a member of the McCreight ministry and criticism arose because he had accepted office under De Cosmos. But McCreight generously stated that Walkem had entered the new ministry with his approval. The De Cosmos government, in spite of the new premier’s protests while in opposition, in the main carried out its predecessor’s programme. One notable omission from the cabinet was John Robson. But Robson was no friend of De Cosmos and probably had no desire nor ambition to De included in the new ministry.

The now familiar “Island v. Mainland” cry had once more been raised, and De Cosmos had attempted to pacify the mainland by selecting two of his ministers from that portion of the Province—Walkem from Cariboo, and Armstrong from New Westminster. But the move was unsuccessful, and the new administration laid itself open to the charge of first preaching economy and retrenchment and then later adding a new portfolio.

Two issues which arose in the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia in the early months of 1873 were the tariff and dual representation. According to the Terms of Union, British Columbia was allowed to retain her own tariff until the completion of the transcontinental railway, “unless the Legislature of British Columbia should sooner decide to accept the tariff and excise laws of Canada.” [49] The Canada Customs Laws’ Adoption Act, 1872, passed by the McCreight administration, had adopted the Canadian tariff. There was much opposition in Victoria to this Act and De Cosmos had been outspoken in his criticism. On January 6, 1873, Arthur Bunster complained in the House that the Lieutenant-Governor had solemnly promised that if he (Bunster) would withdraw his candidacy to the House of Commons and allow Sir Francis Hincks to run in his place, Trutch “would have a modified tariff measure introduced by the late Ministry” and he “regretted that the New Ministry had not foreshadowed any scheme for the Modification of the Tariff.”[50] Bunster’s motion to this effect was lost by a vote of 16-4.[51] Charles A. Semlin on January 10 “asked leave to introduce a Bill to render Members of the House of Commons of Canada ineligible as Members of the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia.”[52] The second reading of this Bill was carried on January 17 by a vote of 13—9; De Cosmos did not vote. The third reading was passed without debate on January 20.[53] The Bill received the Royal Assent on February 21, 1873.[54]

De Cosmos, however, did not resign his seat in Victoria but in March 1873, left for Ottawa where he was active in his support of the claims of Esquimalt as the railway terminal. In his absence Attorney-General George A. Walkem acted as head of the administration. It was now evident that De Cosmos was beginning to lose his influence in British Columbia, but he was still able to command respect. This was shown when he was empowered to negotiate with both the Dominion and British Governments regarding the proposed graving dock at Esquimalt. The fall of the Macdonald ministry as a result of the Pacific Scandal and the rather stiff attitude of Alexander Mackenzie towards the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway impeded the negotiations at Ottawa. In London De Cosmos managed to secure a small loan.[55]

The third session of the First Parliament of the Province of British Columbia opened on December 18, 1873. De Cosmos was still Premier, but the sands in his political hour-glass were fast running out. The Speech from the Throne alluded to the difficulties over the railway clause and graving dock, but stated that the Dominion Government had “agreed to submit a measure to Parliament to carry out the proposal to advance £50,000 in lieu of the guarantee.”[56] A political controversy ensued both inside and outside of the Legislature, and De Cosmos had to face strong opposition.

On February 9, 1874, De Cosmos and Bunster, both of whom had been successful in the elections of January 22 to the House of Commons, resigned their seats in the local Legislature.[57] George A. Walkem became Premier and asked the other ministers of state to remain in office. De Cosmos had now taken the irrevocable step. His political career in British Columbia was over. He had none the less to face an investigation by a Royal Commission regarding certain proceedings in connection with preemptions of land on Texada Island in which he was involved as well as members of his former government. The commission in its report in October 1874, found that “while circumstances apparently suspicious attended the preemptions on Texada Island in August 1873, yet there was not sufficient ground to believe that any member of the late [De Cosmos] or present [Walkem] Government, either by himself or in unlawful or dishonourable combination with any other person, had attempted to acquire the iron of Texada in a manner prejudicial to the interests of the public.”[58]

De Cosmos remained a member of the House of Commons until 1882. He protested against the non-fulfilment of the railway terms. He championed the construction of the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway, the so-called “island section” of the Canadian Pacific. After his return to power in 1878 on the defeat of the Mackenzie administration, Sir John A. Macdonald seemed to favour Burrard Inlet as the terminus of the railway. The Walkem government objected, and in 1880 sent De Cosmos on a rather futile mission to London to lay the Provincial case at the foot of the throne.

In Ottawa De Cosmos also spoke strongly in favour of the expulsion and restriction of Chinese from British Columbia. Arthur Bunster supported him, but their stand that no Chinese should be employed in railway construction in British Columbia met with no support in the House of Commons. De Cosmos’s last speech in the Parliament of Canada was in favour of the right of the Dominion to negotiate her own trade treaties:

“I am one of those who believe that this country should have the right to negotiate its commercial treaties. I go a step farther, I believe this country should have the right to negotiate every treaty. The tendency of this resolution is, as the right hon. the First Minister pointed out, in the direction of independence. I see no reason why the people of Canada should not look forward to Canada becoming a sovereign and independent State. The right hon. gentleman stated that he was born a British subject and hoped to die one. Sir I was born a British colonist, but do not wish to die a tadpole British colonist. I do not wish to die without having all the rights, privileges and immunities of the citizen of a nation.[59]

In the general election of 1882 Amor De Cosmos was defeated. His speech of April 21 had not endeared him to the imperialists of Victoria. He became known ironically as the “nation-maker.” After his defeat De Cosmos retired from politics and lived quietly in Victoria, making his home with his brother, Charles McK. Smith, editor of the Daily Standard. As he grew older his eccentricities increased, and before his death his mind seems to have been somewhat affected. He died on July 4, 1897.[60]60

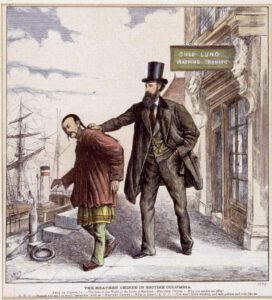

Gilbert Malcolm Sproat, who knew De Cosmos well, has thus described the young political journalist as he first remembered him:

“I first met him in 1860—a tallish, handsome man, pale complexion, dark hair combed back, regular features, set off by a sufficient, shapely nose, addicted to a frock-coat, top hat and big-handled stick hung on the forearm, and not used in locomotion—relic, perhaps, of a western editor’s equipment —such was the man to the eye. He was wide minded, yet methodical, laborious, and a master of details. A great reader, chiefly but not exclusively, in the line of history and politics; he made no parade in general conversation of what he knew, only by some incidental allusion would you become aware of his familiarity with the writings of Shakespeare and Scott. Few ascribed to him humor, but, in reality he had a pretty good, though perhaps rather limited, sense of it.

From a certain reticence, interrogative habit, and occasional irregularities of thought and aim, I should judge that Mr. De Cosmos was, largely, a self-educated man; indeed, he was educating himself all the time with good results, for he was observant, with an active principle of growth in his nature. As a public speaker he was confident and clear but did not stir the audience; the share of humor which he possessed did not appear in his speeches, nor has his newspaper writing much literary grace, notwithstanding his own appreciation of good literature.

From after talk with Mr. De Cosmos, when our intimacy permitted candor, I am inclined to think his was the case of an impulsive man in search of a career, on a larger field than the Pacific seaboard colonies then presented, which career he strove to prosecute by ways that entailed, on the public, certain present sacrifices and risks. It appeared to me that he had from the first mapped for himself a policy and career, which he advocated and followed with persistence, in the firm belief that, ultimately, the public would benefit as much as he, personally, would or might benefit. The East and West were to be one politically, and he, hailing from the West, was to be a political figure in the East. Like Sir James Douglas, whom he constantly assailed, and like Mr. Alfred Waddington, with whom he found it easier to act, Mr. De Cosmos was in relation to the eastern colonies, what might be termed a Pacific seaboard ‘Confederationist,’ though Confederation was not yet a practical question either in the East or the West. Already, too, in conception he was a Canadian ‘Nationalist,’ favoring, nevertheless, a connection of some sort with the Empire. The nature of the connection, he thought, could not be worked out without the prerequisite of Canada’s independence; hence his after nickname of ‘nation maker.’[61]

Sproat was of opinion that “the best of Mr. De Cosmos was not on the surface.” He was “more impulsive than wary” and was unable “to establish an equilibrium between his impulses and the control which they heeded.” This lack of self-control militated against his political success and probably also against his powers as a journalist. He was rather too aloof, too much a “mystery man,” possibly just a bit introverted, to become a great “tribune of the people.” None the less as premier he “approved himself as an unpretentious, most laborious, just and business-like official.”[62]

Such was Amor De Cosmos, a figure of note in the history of British Columbia. In his early days he championed reform and fought Douglas and the Family-Company-Compact. Later he strove for responsible government and for Confederation. Sproat considered that the most notable portion of his political career was after the Union of British Columbia with Canada. Unfortunately, his idiosyncrasies and mannerisms, and possibly too his political inconsistencies, militated against his success. He was a British North American and as such he represented in Victoria a Canadian rather than an English point of view. At Ottawa he was a Canadian from the Pacific Coast. Taken all in all, Amor De Cosmos was a notable figure who deserves more recognition than he has heretofore received.

* Based on a paper presented to Section H. of the Royal Society of Canada in May 1942, at Toronto. As originally written the paper gave more space to De Cosmos’s early life and less to his premiership.

[1] British Colonist, Vol. I., No. 1, December 11, 1858.

[2] ) The political relationship of Joseph Howe to Amor De Cosmos has never been fully investigated. In her valuable M.A. thesis on Amor De Cosmos, A British Columbia Reformer, accepted by the University of British Columbia in 1931, Margaret Ross (Mrs. William Robbins), having discussed the problem in some detail, draws the following conclusion: “It is difficult to prove by direct reference of De Cosmos that he consciously realized the influence of Howe though in many of his editorials one recognizes marked resemblances between the ideas and language of both.” At the time of De Cosmos’s death in 1897 the Victoria papers stated that during his early life in Nova Scotia he chose Joseph Howe for his political mentor.

[3] For the text of this address see Fourth Report and Proceedings of the British Columbia Historical Association, Victoria, 1929, pp. 54—58.

[4] The original narrative bears the stamp: “Library Legislative Assembly Nov. 3 1910 Victoria B.C.” It is unsigned, but the hand-writing was identified as that of Charles McKeivers Smith by the late Beaumont Boggs, and a comparison of the writing with that of letters written by Smith in or about 1863 reveals close similarity. Charles McK. Smith died in Victoria on November 24, 1911, aged 88 years.

[5] D. C. Harvey to R. L. Reid, May 9, 1933. Mrs. Le Noir died May 11, 1938.

[6] A. G. Harvey, “How William Alexander Smith became Amor De Cosmos,” Washington Historical Quarterly, XXVI. (1935), pp. 274—279.

[7] Daily Standard, August 21, 1883. Reply by Higgins in the Colonist, August 22, 1883

[8] The relations between Douglas and De Cosmos are too well known to De discussed at length. See W. N. Sage, Sir James Douglas and British Columbia, Toronto, 1930, pp. 186, 208—211, 288—289.

[9] The connection of De Cosmos with the press may De summarized as follows: The Victoria Colonist, of which he was editor and proprietor, commenced publication on December 11, 1858. The paper remained under the control of De Cosmos until October 1863, when he disposed of it to a syndicate composed of members of the staff. His valedictory, which appeared in the issue for October 7, 1863, states that he sold the paper because of ill-health. Nearly seven years later, on June 20, 1870, De Cosmos published the first issue of a new journal, the Victoria Standard. The next year he sold a half interest in the paper to T. H. Long, and in July 1872, sold the other half to his brother, Charles McK. Smith. Smith bought out Long in 1876, and retained control until after De Cosmos had retired from public life. De Cosmos contributed frequently to the Standard, but always insisted that he had no part in its ownership or management after 1872. (Data supplied, by Dr. W. Kaye Lamb, who has devoted consider able study to the early history of printing and the press in British Columbia.)

[10] In 1860 he was defeated by Captain Gordon, whom he termed the “obstructionist candidate.” De Cosmos ran in that election as “Smith called De Cosmos,” but apparently one voter declared for “De Cosmos” and Gordon was declared to De elected.

[11] Journals of the Legislative Council of British Columbia 1867, New Westminster, 1867, p. 50 (Entry for 18 March 1867).

[12] See F. W. Howay, “The Attitude of Governor Seymour Towards Confederation,” Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada, 3rd Series, Vol. XIV. (1920), Section II., pp. 31—49.

[13] ) Papers on the Union of British Columbia with the Dominion of Canada, p. 13. De Cosmos’s address is given in full on pp. 14—15. Judge Howay’s comments in “The Attitude of Governor Seymour Towards Con federation” are cogent and to the point. “Seymour was a master of evasion and a purveyor of partial and prejudiced information.”

[14] Journals of the Legislative Council of British Columbia, 1869, Victoria, 1869, p. 43.

[15] The Government Gazette Extraordinary of March 1870, published the full text of this Debate on the Subject of Confederation with Canada. The 1912 reprint is, however, now almost as rare as the original. Citations are from the 1912 reprint.

[16] Debate on the subject of Confederation with Canada, Victoria, 1912, p. 31.

[17] Ibid., p. 38.

[18] Ibid., p. 103

[19] Trutch Correspondence, 1871—1879, I., pp. 100—101, in Macdonald Papers, Public Archives of Canada.

[20] Trutch to Sir John A. Macdonald, February 20, 1872, in Macdonald Papers, Trutch Correspondence, I., 144.

[21] Daily Standard, November 21, 1871.

[22] Ibid., January 5, 1872.

[23] Daily British Colonist, January 7, 1872

[24] Daily Standard, January 11, 1872.

[25] Ibid., January 16, 1872.

[26] British Colonist, January 26, 1872.

[27] Ibid., February 23, 1872.

[28] Parliamentary Debates, Dominion of Canada, Fourth Session, 34 Victoria, 1872, Ottawa, Robertson, Roger & Co., 1872, col. 5. (According to the Table of Durations and Sessions of the Dominion Parliament in the Canada Year Book, this was actually the fifth session and it lasted from April 11 to June 14, 1872.)

[29] Parliamentary Debates, 1872, col. 82.

[30] Ibid., col. 129.

[31] Ibid., col. 259.

[32] Ibid

[33] Ibid., May 28, 1872, col. 876.

[34] Ibid., col. 879

[35] Ibid., May 13, 1872, col. 526.

[36] Ibid., col. 642.

[37] Ibid., June 3, 1872, col. 940.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid., col. 941.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid, col 114.

[42] Ibid., col. 808

[43] ibid., col. 809.

[44] Ibid., col. 965.

[45] The reasons for Robson’s action are discussed in W. N. Sage, “John Foster McCreight, The First Premier of British Columbia,” in Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada, Third Series, XXXIV. (1940), Section II., pp. 179—182.

[46] B.C. Legislature, Journal, Vol. II., 1872—3 (Victoria, B.C. 1872), p. 1

[47] ibid., p. 8.

[48] “Prime Ministers of B.C. 2. Amor de Cosmos,” in Vancouver Daily Province, February 15, 1921.

[49] Terms of Union, Section 7. Printed in Howay and Scholefield, British Columbia from the earliest days to the present, Clarke, Vancouver, 1914, II., pp. 665—666

[50] British Colonist, January 7, 1873.

[51] Journals of the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia, Session 1872—73, p. 11.

[52] Ibid., p. 18.

[53] Journals, op. cit., pp. 30, 33.

[54] Ibid., p. 78

[55] Section 12 of the Terms of Union dealt with the question of the graving dock.

[56] Journals of the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia, Session 1873—74, pp. 1—2

[57] Ibid., p. 39. 210

[58] Howay and Scholefield, op. cit., II., p. 337. See “Papers relating to the appointment and proceedings of the Royal Commission for instituting enquiries into the acquisition of Texada Island” (38 Vict. 1874) in Sessional Papers of British Columbia, 1875, pp. 181—246.

[59] Debates, Canadian House of Commons, 1882, Ottawa, 1882, col. 1084 (April 21, 1882).

[60] The inscription on De Cosmos’s tombstone in Ross Bay Cemetery, Victoria, reads as follows: IN MEMORY OF THE HON. AMOR De COSMOS WHO DIED AT VICTORIA B.C. JULY 4th, 1897, AGED 72 YEARS LESS 1 MONTH AND 16 DAYS A NATIVE OF WINDSOR HANTS COUNTY, NOVA SCOTIA A FAITHFUL SERVANT OF THE PEOPLE, NOW AT REST

[61] “Amor De Cosmos, a singular figure in B.C. Politics,” Victoria Daily Times, January 19, 1906.

[62] Ibid.