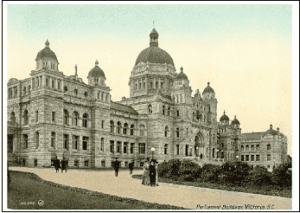

The Building of the British Columbia Legislature

Ken Johnson

If you were to ask a British Columbian who “built” the British Columbia Legislative Buildings, a frequent reply would be Francis M Rattenbury. Yes, Rattenbury was the Architect, but the building was done by an unsung and unrecognized group of tradesmen; some local but many itinerant, following major projects across the continent.

For Rattenbury, the project was a major opportunity, a challenge that vaulted him ahead of many large, better established architects, but also a project that caused him great embarrassment before it was done.

For Frederick Adams, a stone mason trained in England and having a small contracting business in Victoria, the Legislative Building presented a great opportunity to become a major contractor but, for him, the project evolved into death and tragedy.

“HUGE MASSES OF GRAY STONEWORK”[1]

In June, 1892, the Provincial Government issued an invitation to architects to submit “…competitive plans and estimates of cost for the construction of certain Provincial Government Buildings.[2] The winning design was submitted by the young English architect, Francis Mawson Rattenbury[3] and, in March of 1893, he entered into a contract with the Provincial Government to “prepare in the most thorough and careful manner the necessary drawings, specifications and all other information required to the proper and efficient erection of the new Administrative and Legislative Buildings proposed to be erected at Victoria, …[4].”, with a total cost of construction not to exceed $550,000.

On April 6, 1893, the following advertisement appeared in the Victoria Colonist:

“To Quarry Owners

The undersigned will be glad to receive samples of Sandstone, dressed and undressed, with particulars of amount procurable, price per cubic foot, etc.

F.M. Rattenbury

Architect for the Government Buildings, Victoria, BC “

Various samples of stone were obtained from the better quarries and the properties of the stone as to strength and mineralogy were tested by the Provincial Assayer (Herbert Carmichael) in the Department of Mines.[5] Where possible, the quarries were visited by Rattenbury and the Honourable W.S. Gore, the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works (CCLW)[6]. In September 1893, Rattenbury selected two sources of stone for use on the new Parliament Buildings in Victoria; Haddington Island stone, from the island located off Port McNeil at the north end of Vancouver Island, and Koksilah stone which could be obtained from the Koksilah quarry located within the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway (ENR) right-of-way at Cowichan Station a few miles south of Duncan, B.C.[7]

Under the terms of the acceptance letters, the owners of the quarries were each to supply about one-half of the estimated 60,000 cubic feet of stone required for the new buildings. The Haddington Island stone was to be supplied by the Haddington Island Quarry Company (owned by A.W. Huson, Henry Rudge, and Samuel Grey); the Koksilah stone was to be supplied by the Koksilah Quarry Co. Ltd. (operated by T. Lubbe of Victoria on land leased from the ENR).

The stone was to be supplied to the building site on the grounds of the new Parliament Buildings and be in blocks sized to meet the requirements of the mason who had not been selected in September of 1893. The majority of the stone would be supplied at a price of $0.50 per cubic foot for the Koksilah stone[8] and $0.58 for the Haddington Island stone.[9] The higher price would reflect the greater costs of extraction and transporting the Haddington Island stone to Victoria.

For the owners of the Haddington Island quarry, the large contract had to be a tremendous windfall. They had done some minor work on the Island but, at the time of the contract, had done little in terms of supplying stone to a building project. They were greatly underfunded to carry out the works of extracting large quantities of stone and shipping them to Victoria. In order to raise the required operating capital, Rudge, Huson and Gray, on October 31, 1893, entered into a mortgage agreement with W.J. Macaulay of Victoria indenturing Haddington Island in return for $3,500 for a period of one year and at an interest rate of 12% per annum.

The construction on the new Parliament Buildings had commenced in the fall of 1893 when, on September 30, 1893, the Honourable W.S. Gore, CCLW entered into a contract with the Joseph E. Phillips Company to carry out the site excavations and the placing of the foundations for $54,790.[10]

On November 30, 1893, Contract No. 2 for the construction of the buildings closed. The lowest tendered price for the Mason’s portion of the works, $413,261, was received from a Tacoma contractor, Mr. R. Nichols. This price, when taken in addition to the other contractors, resulted in a price for the buildings of $617,574, far above the $550, 0000 amount Rattenbury had promised the Government. In addition, the Government had strongly expressed the need to utilize local, British Columbia, contractors and materials as much as possible. The next lowest bidder was Frederick Adams, a Victoria mason who had submitted a price of $454,508. Rattenbury suggested that, by deleting certain items from the building and by negotiating with Frederick Adams, the total costs for the building could be brought to the desired levels[11].

Following discussions with Adams, the necessity for a bond was removed from the contract, certain items were deducted from the Plans and Specifications, having been called up twice (?), and Mr. Adams made an absolute deduction of $10,000. The resulting contract was awarded to Adams on December 6, 1893 for $380,000.

Under the terms of the contract Adams was to enter into agreements with the two quarry companies for the supply of the stone and did so, with the Koksilah stone supplier on January 2, 1894 and with the Haddington Island stone supplier in mid-January, 1894.[12] On January 27, 1894, the Victoria Colonist reported that, “Mr. F.M. Rattenbury, architect for the new Parliament buildings, is one of the party of experts who left on the steamer Mystery yesterday for Haddington island, where the quarries are located, from which the stone for the new buildings is obtained. The party expects to return early next month.” On February 7, 1894, the Victoria Colonist reports of the S.S. Boscowitz “she sailed North last evening. Her decks were well filled with freight, the bulkiest of which was lumber. Her passengers included W. J. Woods, Theo. H Robinson, G. Williscroft, John Flewin, Charles Todd and wife, and A. Rudge. The last-named gentleman is bound for Haddington Island, to open up the stone quarries there so that the supply for the new government buildings can be obtained when required.” From the same source we find:

“Among the passengers on the Boscowitz for the North Monday were H.M. Wright and Wm. Hartley, with the quarrymen, for the Haddington Island stone quarry. Mr. Wright goes up as superintendent, while Mr. Hartley, who is an experienced quarryman, will have full control over the quarrying out and squaring up of the stone. Heretofore the work of the quarry has been seriously hindered through lack of room, and the company were obliged to send down the first scow load of stone for the Government buildings without the proper squaring up and trimming, but it has been decided to open up a part of the quarry, and this will give ample room for all working and loading of the stone. It will require three- or four-weeks’ time to get the quarry re-opened and a scow load of stone brought down, but after the load it will be delivered on the Government grounds at the rate of two thousand feet, or over, per week.”

From the above it would seem that the Haddington Island quarries were not fully ready to supply the required stone after being advised that the material had been approved for use in the new Parliament Buildings. As well, the Haddington Island Quarry Co. had failed to meet their obligations of interest payments under their mortgage with W.J. Macaulay and, in a letter to the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works, Macaulay requested that his name be removed from the list of bondsmen for the stone supply contract.[13] This matter was of concern to the Government and, on February 1, 1894, Rudge, Huson, and Gray signed an agreement with the CCLW pledging all of their rights to Haddington Island (subject to the Macaulay mortgage noted above) as well as posting a $20,000 bond to ensure that the Haddington Island Quarry Company would supply the stone as contracted.[14]

PROBLEMS WITH KOKSILAH STONE.

“If sandstone is exposed to frost action while the pores are filled with water, the expansion caused by freezing may result in serious disintegration. Blocks should therefore be quarried in time to dry before a heavy frost. Quarrying is usually suspended in cold climates during the late fall and winter”.[15]

The Koksilah quarry delivered the first loads of their stone sometime about the middle of February 1894. This would have been the first opportunity for all parties to view larger quantities of the two types of stone upon the same site. There had been a period of rainy weather followed by snow and temperatures below freezing on February 18th and 19th .[16] On the 22nd, the contractor, Adams sent a letter to T. Lubbe, the agent for the Koksilah quarry, stating that, “about 2/3 of the stone as delivered had split all to pieces.”[17] On the same day, February 22nd, Adams sent a letter to Rattenbury that the Koksilah stone on site did not in any way comply with the project specifications.[18] Rattenbury quickly wrote to the Honourable F.G. Vernon, Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works, recommending that the Koksilah stone be rejected and replaced with the Haddington Island stone.

On February 27, 1894, the Koksilah quarry company delivered stone to the site which was to replace the rejected pieces. These were rejected out-of-hand by Adams[19] and later that day the Government, upon the recommendation of the Architect, passed an Order-in-Council replacing the Koksilah stone with the Haddington Island stone.[20] Following this Adams, as the contractor, advised the Koksilah Quarry Co. that all the stone on site was deemed unacceptable and that Haddington Island stone was being substituted.[21]

The Koksilah Quarry Co. sued the Government for breach of contract.

The case, Koksilah Quarry Company versus The Queen, did not reach the Courts until the Fall of 1896 with Rattenbury being the Government’s main witness. While we don’t have the transcripts of his evidence at the Trial, we do have his notes submitted to the Government pertaining to the statements of claim filed by the Koksilah Quarry Company at the time of the lawsuit. In this document Rattenbury places all of the fault for the rejection of the stone upon the Koksilah Quarry Co., that the quarry owners should have known they could not supply suitable stone in the wintertime and further stated that the stone was unsuitable and that the stone supplied was different from the stone that had been tested at the time of tendering.[22]

On December 29, 1896, the Trial Judge found for the Plaintiffs, the Koksilah Quarry Co. and stated that:

“No complaint as to the quality of the stone was made until after the first delivery of 170 pieces, out of which only 27 were rejected, and these Mr. Lubbe promptly offered to replace – Adams observing that this was all “that could be expected.” The lot was critically examined by Mr. Adams’ foreman and the quarry foreman jointly, with the result stated.”[23] Under cross examination Mr. Lubbe stated, “It was decided that as my stone was darker than the Haddington Island stone it was to be used on the south. I went to see Mr. Vernon but didn’t see him. Mr. Gore went with me to the architect, and he said he couldn’t accept Koksilah if the building was to look well.”[24]

Further, the Trial Judge agreed that the appearance of the buildings would have been marred through the use of the Koksilah stone and that he was “not surprised at the architect abandoning such a grave mistake.[25] The rejected stone, valued at about $2,000, was sold for $54 and used in the Jubilee Hospital Additions, John Teague, Architect.

It is interesting to note that the Koksilah stone was used in the construction of two prominent Victoria buildings: Craigdarroch Castle in 1896 and the Methodist Church (now Conservatory of Music) in 1890. Both structures are in excellent condition at this date, over 100 year later.

RATTENBURY RECOMMENDS SEIZING THE QUARRY

A short piece in the Victoria Colonist of April 27, 1894 stated,” The steamer Coquitlam, which last evening left for Haddington Island for a stone cargo, carries up 12 men and some new machinery to put into operation the two additional derricks that were set up on the last trip. A stock of provisions was also shipped yesterday, the proprietors being determined to have ample machinery upon the ground to make the quarry one of the finest north of San Francisco.”

Despite this further investment of men and machinery and despite having opened up a second quarry on the island, in late April of 1894 it had become evident that the Haddington Island Stone Quarry Co. could not meet the demand for stone at the site of the new Parliament Buildings. Work was falling behind schedule and the stone which had been delivered was of a poor quality only suitable, in Rattenbury’s opinion, for use in the back of the building. Work was not being done on the front of the buildings nor was there any prospect of stone being received to allow such work to begin. In a letter to the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works, dated April 24, 1894, Rattenbury recommends, “I should advise that the control of the quarry is taken out of the Haddington Island Stone Co. hands according to the agreement made with them & which they have not fulfilled in any respect – and that the Government enter into a new contract with responsible parties to deliver stone from this quarry at the prices agreed upon – or else that a competent foreman be appointed to work the quarry on behalf of the Government.”[26]

Following Rattenbury’s letter, the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works advised the quarry owners that, “…. If a cargo of stone from the No. 2 Quarry of suitable character for the front of the building is not delivered here within one fortnight from date that Mr. Rattenbury’s recommendation will be adopted, and the Government will enter into possession of the quarry without further notice to you.”[27]

The problems with the delivery of stone continued however and, on June 12, 1894, the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works advised Rudge, Huson and Gray, the owners of the Haddington Island Quarry Co., that the quarry was forfeited under the agreement of February 1, 1894, and that the Government was seizing the quarry for the purposes of completing the extraction of stone for the new Parliament Buildings.[28]

It is evident that the stone supply problem had been a subject of prior discussion, for on the same day, an agreement between the Contractor (Adams), Rudge, Huson, and Gray, and the Government was signed. This permitted the Contractor to enter upon Haddington Island and, using the equipment thereon, to remove such stone as would be required for the new Parliament Buildings. The Contractor would make a royalty payment of $0.05 per cubic foot to the Government which payment the Government would hold for the benefit of Rudge, Huson, and Gray. At the conclusion of the building, the plant and equipment were to be returned to Rudge, Huson and Gray in “sound working condition.”[29]

There is no evidence that Adams, as the Contractor, received any benefit from the agreement. He was, in fact, assuming greater responsibilities at a time he was beset by other problems. Adams had been paying the Haddington Island Quarry Co. an average of $0.49 per cubic foot of stone delivered to the site.[30] As a result of the agreement of June 12, 1894, he must assume all costs for the quarrying and transport of the stone from Haddington Island to Victoria and pay the $0.05 per cubic foot royalty to the quarry company.

HIRING OF AMERICANS.

On Wednesday, May 16, 1894, a Letter to the Editor appeared in the Victoria Daily Times[31] complaining that the work on the New Parliament buildings was not being given to local workers and that Frederick Adams was showing a preference for ‘men from the Sound”, i.e., Americans from the Seattle area.

Adams responded with a Letter to the Editor of the Daily Colonist, published on May 19, 1894,[32] stating that he had not sought to hire workers from the United States and that, when he does require workers, he hires the best available. The rumours regarding Adams’ hiring practices continued however and, as a result, a second Letter to the Editor of the Victoria Colonist was run on May 31, 1894[33] in which Adams listed all of his workers with their names, trades and nationalities. Of the 104 men listed, only seven were Americans and two were Germans. The remainder were of British citizenship although whether or not they were local men was not indicated.

STONECUTTER’S STRIKE

On Friday, June 15, 1894, as Adams was dealing with the taking over of the Haddington Island quarry, Jacob Durst, a stonecutter on the site of the new Parliament Buildings, had a large piece of granite, which was being prepared for a stair, crack during the shaping process under a hammer and chisel and be spoiled for its intended use. Adams on his return to Victoria told Mr. Durst that, unless he paid for the damaged stone, he was laid off. Mr. Durst refused to pay and was discharged. The Stonecutter’s Association, the early workman’s organization existing at that time, took the position that, unless Mr. Durst was reinstated without loss of pay, they would go out on strike and did so, on Thursday, June 21, 1894.[34]

During the last session of the Provincial Legislature, the Government had passed a new act to deal with labour disputes, the “Councils of Conciliation and Arbitration Act.” Under the Act each party to the dispute, including the Government, nominated members to represent their viewpoint: they also nominated other disinterested parties as Conciliators and from these a Chair was selected. The Council met on June 24, 1894, and received evidence from all the parties involved and, on Monday, June 23, 1894, the parties agreed that Mr. Durst would receive his wages in full and the stonecutters would return to work. There is no evidence that Mr. Durst continued in the employ of Adams when the stonecutters returned to work on June 26, 1894.[35]

GOVERNMENT PURCHASE THE MORTGAGE.

On November 5, 1894, the Government purchased the mortgage on Haddington Island from W.J. Macaulay for the sum of $3,860 including all principal and interest. The indenture was made between Macaulay and by G.B. Martin, Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works.[36] Rudge, Huson and Gray were advised by letter of the purchase and further advised that the sum of $3,860 was now due. While the property remained in the name of Rudge, Huson and Gray, a charge upon the property for the amount of the mortgage was registered at the Lands Titles office in Victoria.

ADAMS – CAPITAL WAS LACKING.

Throughout the summer and early fall of 1894 work progressed with few problems on the New Parliament Buildings. The tug Velos and a barge had been contracted to bring stone down from the quarry. But, in November it became evident that problems between Adams and Rattenbury were beginning to surface. A letter from Theodore Davie, the Attorney-General, to Adams states that;

“Mr. Rattenbury, Superintending Architect, has made complaint to me that you have, in manner offensive to him, disputed his authority in matters coming within his jurisdiction and intimated your intention of appealing to me for settlement.

Permit me to state that I have no authority or desire to qualify or restrict the powers of the architect as derived from the terms of the contract governing his relations with yourself, and that any complaints as against him must be referred to the Commissioner of Lands and Works.

Furthermore, I trust that he will not have cause in future to complain of offensive references to his position.”[37]

From the above it is evident that those differences between the Contractor and the Architect existed, and that the Contractor had threatened to take the matter to the Attorney-General. Rattenbury forestalled Adams’ action by going directly to the Attorney-General and placed his complaints first, which resulted in the letter.

Adams responded with a letter to the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works stating that Rattenbury was making changes to the buildings and refusing to provide the Contractor with the Change Orders that were required before payment could be received, that changes to the specifications for the south end of the building were driving costs to twice what had been estimated, and that the costs of bringing the stone from the quarry were resulting in a loss of $0.26 per cubic foot.[38]

On November 22, 1894, Rattenbury, in a letter to the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works, responded to Adams’ letter stating that the problems were of Adams own making in that it was he (Adams) who had urged the change in stone for the south side of the buildings and that it was he (Adams) who had taken on the contract to supply the Haddington Island stone when the Haddington Island Quarry Co. had failed and all was the result of his (Adams’) lack of business knowledge. Rattenbury admits to making some additions to the works but that he, as the Architect, should establish the value of the changes; not the Contractor. Rattenbury further refers to the clauses in the Contract that say he is in charge of the project and “That he is subject to my authority & that no attention will be paid to his complaints against myself.”[39]

The Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works, in a letter to Adams dated November 27, 1894 took the side of Rattenbury in the dispute, stating that, “In the absence of fraud or misconduct on the part of the architect, his decision is final and I must so regard it “, and, “… that unless you are prepared to shew Mr. R’s answer to be untrue, or that he has been guilty of misconduct, it will be useless for you to prolong the complaint, as contempt for the architect’s authority will not be tolerated in any case.”[40]

This exchange did nothing to resolve the problems that Adams was having. He had exhausted all possible funding sources, pledging any profits to the Bank of British Columbia in return for a line of credit for operating capital which he had now expended. Adams responded to the above letter by requesting a hearing with the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works regarding the statements made by Rattenbury in his letter of November 22, 1894.[41]

A few days later, on November 30th, Adams was again writing to the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works complaining about Rattenbury’s actions:

“I beg to inform you that this morning I asked Mr. Rattenbury for the certificate due me today for work done on the buildings.

I regret to say that Mr. Rattenbury refused to give it to me and also stated that he was authorized to keep back the sum of $10,000 out of the payment due this month.

As it is necessary for me to have the money to carry on the work, I must ask you to investigate the matter at once and arrange a settlement with me sometime today otherwise I can see no other way out of it but for me to stop the work tomorrow.”[42]

It appears that Rattenbury was now going to apply the contract to the fullest letter of the law and start holding back payment at the 25 percent level. He was further exercising his right as Architect to not issue certificates of works completed until all is to his satisfaction. These actions are a change from those prior to this time as the hold back amount had previously been as low as 5 percent and are an indication of the animosity that had developed between the Architect and Adams. Over the next two months this hostility would continue to grow.

On December 1, 1894, Adams was unable to meet his payroll. Rattenbury met with the Hon. George Martin, the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works to review the problems of cash flow and completion. In the interim, the Government agreed to pay the wages of the workers on the new Parliament Buildings directly so as to keep the work progressing. Martin expressed a desire to have the Contractor continue with the work; a change in contractors could prove embarrassing to the Government. Rattenbury was not sure that the Contractor was actually losing money and suggested that Adams open his books to examination by the Government. Rattenbury suggested other options to the Government; they could continue to support the existing contract, picking up any losses but using Adams only in a managerial position; appoint a different manager (Rattenbury suggested his Clerk of Works, E.C. Howell) to supervise the works; or a new tender could be called to engage another contractor.[43]

The parties did come to an agreement that Adams should open his books to the Government; this would allow the Government to better access the state of the Contract. Unfortunately, Rattenbury engaged the services of a bookkeeper (a Mr. Paterson) that had recently left Adams’ employ and Adams refused to allow this person to interpret the state of the books for Rattenbury.[44]

Again, matters reached critical proportions when, on December 10th, Adams wrote to the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works that Rattenbury had held back, from the most recent progress payment, the sum of $7000 as well as an additional $2077 for wages to the workers previously paid by the Government on behalf of Adams. This left Adams short of funds to pay current wages and he requested that the hold back be re-calculated and paid to him. Adams also requested that the existing state of completion on the new Parliament Buildings be measured up and valued in conjunction with his (Adams’) consulting architect (Edward Mallandaine, Jr).[45] At the end of that day Adams ceased work on the project. Telling the men that he could no longer pay them and that they were laid off; he was essentially in a position of bankruptcy. There was a shortage of stone upon the site as Adams had been unable to pay the contractor (a Mr. Tulloch) he had engaged to quarry and supply the stone from Haddington Island. Public expectations were that the Government would step in and take the works over from Adams and would not experience any additional expense above that already contracted.[46]

We have, in the B.C. Archives, a copy of a letter from the Chief Commissioner of Lands and works to Adams stating;

“I consequently am compelled to notify you, which I hereby do, that without any legal or further notice I forthwith suspend all further payments to you and that I hereby enter upon and take full possession of the permanent and temporary works completed or in progress with plant, tools, materials, erections and things, on behalf of the Government of British Columbia and that I shall exercise my power to carry on the execution of the works on behalf of the said Government of British Columbia by their servants, or shall re-let the same, or advertise for tenders for completion as I deem fit, retaining all moneys due to you until all expenses which I may consider to have been necessary have been defrayed. And I hereby warn you not to remove off the grounds any plant, tools, materials or erections until you are authorized by me to do so at the completion of the works.”[47]

A handwritten notation in the upper LH corner of the first page states, “Not sent.”

It appears that, at this point, one or more elected officials of the Government stepped in. If another contractor had to be found or if the government publicly took over the contract there would be a great deal of embarrassment to the government as well as the probability of cost increases. A series of meetings were held between Rattenbury, Adams, the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works, and Mr. John Turner, then a member of the government and soon to be Premier.[48] A condition almost akin to open war existed between Adams and Rattenbury; “they both became at those meetings exceedingly excited and there was very great difficulty in keeping them apart.”[49] Despite the shouting matches between Adams and Rattenbury, an uneasy truce was attained wherein Adams would continue the works with the government paying all bills and wages, allowing a 15% markup for Adams,[50] and Rattenbury and the architects assigned by Adams[51] (Messrs. E. Mallandaine, Thos. C Sorby, and E. Mallandaine Jr., Architects) would measure up and re-evaluate the works. Adams was required to write a letter withdrawing allegations he had made in meetings “that the quantities prepared for the Government buildings are deliberately in error as compared with the works as executed.”[52] Matters were not resolved but “only been tided over.”[53] During this period and over the next few months, Edward Mallandaine Jr, Architect, became more involved in the management of the project and worked closely with Adams’ foreman, Mr. Spittlehouse.[54]

It was at this time that questions were raised in the Legislature regarding the state of the contract and the progress on the new buildings. The initial plan had been for the new parliament buildings to be roofed by October 1894 but, as of December 1894, the walls were only partially up, and the closing of the roof looked to be done in the fall of 1895. A Select Committee was appointed in late December to look into the causes of the delays and of the situation with the Adams contract which was believed (correctly) to be without security.[55]

As work continued, albeit slowly, on the buildings, the Select Committee met through the month of January, calling witnesses and gathering evidence. The meetings were closed so that daily accounts of evidence presented were not available. Adams was still not being paid. In a letter to the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works he complains that Rattenbury has not approved a certificate for payment since October 31, 1894.[56]

By early February, the Victoria Daily Times began a series of “Letters” and editorials keeping the matter before the general public and pressure upon the government to provide information. These “Letters”, which were more in nature of editorials, revealed that Mr. George Martin, then Chief commissioner of Lands and Works was a “close personal friend” of a “government official” who was a partner of Mr. Adams in the Mason Work Contract.[57] On February 6, 1895, the Victoria Daily Times reported that, as a result of the delays in the construction, the workmen at Haddington Island, engaged in the quarrying of the stone, were without money or food and required immediate relief.[58]

Finally, on February 9, 1895, the Select Committee presented its Report to the Legislature.[59] The main evidence was given by Rattenbury and Adams and, again, they disagreed. Adams felt that he was entitled to an extra due to the change made in the selection of stone. Haddington Island stone was more costly than the originally specified Koksilah stone and required more expense to work. In addition, the architect was making changes to the buildings and not allowing any ‘extras’ or valuing extras at too low a price. Rattenbury, as the architect, insisted that even though the stone had been changed the contractor had incurred no additional expense and was not entitled to more money on account of the change in stone and, in fact, the change in stone was made at the request of the contractor. Rattenbury further stated that Adams was only owed $26.33. (This took some imaginative book-keeping on the part of Rattenbury as evidenced by his letter to the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works dated January 18, 1895).[60]

The Select Committee found that any bonds that had been provided by the contractor were gone and that the government was without security to the completion of the contract. The Committee further felt that they could not fully examine the question of extra costs incurred by the change in stone as the matter was now the subject of litigation between the Koksilah Quarry Co., and the government. The Select Committee noted, that “The disputes thus existing between the parties (Adams and Rattenbury) should, in the opinion of your committee be arranged and settled without delay, otherwise serious complications may arise.” and, “The work on the buildings is not progressing satisfactory, and never has progressed at the rate it should have done, and according to the present rate of progress it will take about 18 months for the completion of Adams’ contract.”

By February 14, 1895, the Legislature was discussing the Report of the Select Committee even though no official copy had been printed and distributed to all of the members of the Legislature. As the time was fast approaching for the legislature to prorogue, some members wanted the House to extend its sitting by a week to allow the materials to be printed, distributed and discussed. On the government’s side, there was a request for the Select Committee to continue its hearings as there were indications that some of the evidence may have been false or forged.

The government also stated that, as there may have been false evidence, the Report could not be printed and distributed.[61]

The following day the Premier, Mr. Theodore Davie, in motioning that the matter should go back to Committee, stated that the government had plenty of security including the bonds placed at the signing of the contract and that, in respect to the change in stone; it was the responsibility of the contractor and not of the government. The false or forged document referred to on the prior day had been altered to place the government in a position of responsibility for all extra costs incurred due to the change in stone and, for this reason the Committee should continue to meet. The opposition rose and presented the true document which showed that the government had, indeed, made the guarantees to the contractor. As a result, the Premier apologized to the Chair of the Committee for suggesting that he had deliberately allowed a false document to be introduced to the evidence.

Mr. Aldolphus Williams was the member from Vancouver city and the Chair of the Select Committee and responded to Mr. Davie that, “Mr. Adams’ tender was reduced by the architect to bring the contract within the estimated cost of the building. They reduced the cost of certain things but they all will have to be restored to complete the building.” Other members expressed the opinions that, “Mr. Rattenbury may be a very good architect but he is having too much his own way. He is a young man with a big head.”, and “…a good deal of the trouble had been caused by the architect.” But, with the government majority, the motion was passed, and the Report was passed back to the Select Committee even though it was agreed that there would be no time for the Committee to meet and report before the House dissolved.[62]

On February 20, 1895, the House adjourned with the motion moved and passed that, as the Select Committee had not had time to report, a Royal Commission be appointed to look into the construction of the new Parliament Buildings. Mr. Theodore Davie resigned to take up the position of the Chief Justice of Canada, his position of Premier of British Columbia being taken up by Mr. John Turner. Much had been discussed and argued; the problems between Adams and Rattenbury continued unabated. As a result of the evidence presented, new events would unfold, piling disaster upon disaster for Adams.

TROUBLE AT THE QUARRY

On March 7, 1895, Rattenbury sent a letter to the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works stating that:

- Adams was taking stone below the tide level at Haddington Island, this stone contained excessive salts, and salts in the stone would be detrimental to the buildings,

- The Provincial Assayer could not detect any salts at this time but there was more iron present than previous tests and this could be “disastrous” to the buildings,

- He had ordered Adams’ foreman not to use any of the stone on the front of the building or it would be at his own risk, and,

- As Mr. Howell (Rattenbury’s Clerk of Works) was proceeding to Haddington Island, may he be allowed to advise Adams that “as the stone quarried in the present position is not of the quality specified, that this stone will be condemned in toto if delivered.”[63]

On March 11, 1895, Mr. Howell arrived on Haddington Island and, upon landing, handed Adams two letters, undoubtedly listing the complaints Rattenbury had concerning the stone. Upon opening the letters, Adams assaulted Howell, knocking him to the ground and threatening Howell and Rattenbury that he, Adams, “was determined to “do” them if he spent the remainder of his days in penitentiary in consequence.”[64] Howell immediately left the island and proceeded, by way of Comox, to Victoria. Charges were laid in the assault and Adams, returning to Victoria on Monday, March 18th, was charged the next day with aggravated assault upon Howell. A trial was held, and, on March 20, 1895, Adams was found guilty of assault and fined $25 and costs and required to post bonds to keep the peace for six months.[65]

THE WRECK OF THE VELOS.

At 9:30 of the evening of Friday, March 22, 1895, Adams boarded the steam tug ‘Velos’, which, with the barge ‘Pilot’ (a converted steamer) in tow, left Victoria harbour bound for Haddington Island. On board the towed barge were 12 workers bound for Haddington Island and 11 workers for Nelson Island where the granite for the new Parliament Buildings was being obtained. As well as Adams, the ‘Velos’ carried a crew of six. Encountering a southeast gale in the Straits of Juan de Fuca, the ‘Velos’ was delayed and, at about 10:30 pm was just entering the pass off Trial Island when the wind rose and made any headway difficult with the barge in tow. Deciding to return to Victoria, the ‘Velos’ reversed course but was caught between the wind and the flood tide and lost her rudder chains. Out of control and in a raging storm, she quickly went awash and was thrown up on the San Pedro rocks near Trial Island. The barge went aground on an adjacent rock where she sat until the dawn, all aboard the barge were safe but spent the night listening to the desperate cries of their comrades — the dying and the survivors. The Captain of the ‘Velos’ was washed onto a rock, where he was recovered in the morning, and the mate shinnied to relative safety up the tow rope to the barge. The five others on board the ‘Velos’ were all lost. The body of Adams was never found.

By a strange coincidence, Adams, on the day of his death, had made out his will, leaving everything to his wife, Sarah.

THE WORK ON THE NEW PARLIAMENT BUILDINGS CONTINUES.

On the 20th of March 1895, the day Adams had been found guilty of assault, the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works had prepared a letter to Adams stating that, on or before March 26, 1895, Adams must present a plan for the financing and completion of the New Parliament Buildings. Unless this was done, the contract would be taken away to be completed by the government or to be re-let as the government would see fit.[66] The letter is marked ‘Not sent.’

On March 21, 1895, the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works advised the Bank of British Columbia, which held the liens against Adams’ accounts and equipment, that unless matters were resolved by March 26, 1895, the government will take “such steps as they may deem expedient for the due completion of the Parliament Buildings.”[67] The Bank of British Columbia replied the same day that “every effort is being made to complete arrangements for satisfactorily carrying out the contract in question, and that the necessary documents are now being prepared by our solicitor for execution by the parties interested.”[68]

The government wanted some security that the contract would be completed without further financial problems and, as a result of the negotiations being carried out, a bond in the amount of $20,000, guaranteeing the “due fulfillment of the Adams contract’ was placed as security by three Victoria businessmen, Moses McGregor, George Jeeves, and James Baker. The bond, received on March 22, 1895, the day of Adams’ disappearance, was found somewhat irregular and a fresh bond was requested.[69] McGregor and Jeeves were building contractors in Victoria as well as operating a small brick manufacturing facility on what was then the edge of the city. James Baker was engaged in brick manufacture in a nearby location and had obtained the contract to supply the many hundreds of thousands of bricks needed in the construction of the new Parliament Buildings.

Immediately after the loss of the ‘Velos’ and the disappearance of Adams, even as the search for the bodies of Adams and the others continued between March 23 and March 26, 1895 and thereafter, the resolution of the contractual problems proceeded. On March 27, 1895, the solicitors for Sarah Adams, the widow of Frederick Adams, filed the last Will and Testament of Frederick Adams, “in writing dated the twenty second day of March One thousand eight hundred and ninety-five, devised and bequeathed to his wife the above bounden Sarah Adams all his real and personal property whatsoever and appointed her sole Executrix of his said Will.”[70]

As the original Contract No. 2, signed December 6, 1893, between the government and Frederick Adams obligated Adams and “his heirs executors administrators and assigns”[71] to complete the contract, this responsibility now fell upon his widow, Sarah Adams and upon his guarantors of March 22, 1895, McGregor, Jeeves and Baker.

In an affidavit, dated March 29, 1895, addressed to the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works and signed by Sarah Adams, Moses McGregor, George Jeeves, and James Baker, the parties pledged to complete Contract No. 2 for the construction of the new Parliament Buildings as they, and Frederick Adams when alive, had agreed to do.[72] The newly composed performance bond, naming Sarah Adams, executrix of the estate of Frederick Adams, and the others was submitted.

On April 15, 1895, a report was presented to the Executive Council of the Government, which stated that:

- The bond provide was satisfactory to the government,

- That McGregor, Jeeves, and Baker would complete the works of the new Parliament Buildings, and,

- That the government would provide cash advances to the contractors in the amount of $18,222[73]

Further commitments were made by the parties regarding the payment of funds directly to the Bank of British Columbia in order to satisfy the bank’s concerns for the security of its loans.[74]

From this point onwards, the work on the new Parliament Buildings proceeded quickly and with greater cooperation between all parties. Frederick Adams’ eldest son, John Henry Adams, who had been employed by his father as a draughtsman, represented his mother’s interests in the continuation of the contract. On May 23, 1895, in honour of the celebration of the Queen’s Birthday, the site of the unfinished buildings was opened to the public for tours and inspection. While works on the building would be suspended for the day, “the stone yard will be in full operation”.[75]

Between the 1st of April through to the 1st of November 1895, works to the value of $153,331were completed and paid for.[76] This eight-month period represented 52% of all work done over the 23-month period since the contract had been entered into.

The Year-end Report of the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works for the year 1895 was able to state:

“The work of construction has been carried on during the past season in a most satisfactory manner. The mason’s work on the central building has been completed, the roofing is nearly finished, and the work of the other trades is well advanced. All the buildings will probably be ready for occupation next winter.”[77]

On September 19, 1896, the last stone in the east wing was laid by Premier John Turner and the buildings were completed in late 1897 with an official opening on February 10, 1898.[78]

McGregor, Jeeves and Baker submitted their last, major invoice in July of 1896. In November of 1896, the Contractors, acting in the name of the Executors of the estate of Frederick Adams, submitted a claim for ‘some $60,000′[79] for extras and changes to the buildings. Rattenbury and Howell, who had been Superintendent of Works for the project since the Spring of 1895, objected to the claim with Rattenbury further contending that the Contractors had, by his calculation, already been overpaid some $5000.[80] At this point, the politicians entered into the negotiations and, on February 1, 1898, an Order-in-Council approved the payment of $30,000 to the estate of Frederick Adams as a compromise settlement of the outstanding claims. Subsequent to the receipt of this payment, McGregor, Jeeves and Baker claimed a further $19,000 but settled, in arbitration during the summer of 1898, for between $6000 and $7000.

These extra payments, made over the objections of the Architect and the Superintendent of Works, resulted in a Royal Commission being called in the Fall of 1898. The findings of the Royal Commission were inconclusive probably due to the statement entered by the Hon. John Turner, then Premier of the province which addressed Rattenbury’s position regarding the claim:

“It was evident to the minds of the Government that the architect was very anxious and very rightly so to keep down the expenditure on the buildings to the very lowest point. He had made a boast of the fact that there would be no extras on that building and he evidently was endeavouring to keep up to the statement he had made in that respect, on the other hand, the builders, the contractors, claimed they were entitled to very large amounts; that the building had been changed in many points; that additional work had been put on it and that, generally, they had a very large claim.” [81]

The Hon. John Turner went on to say, “…. but we were convinced that the contractor was entitled to a very considerable amount of money.”, and “…. so that the government had not the utmost confidence in his (the architects) figures owing to the clerical inaccuracies which extended to very considerable sums during the Adams time.”[82]

It is interesting to note that, in a letter to the then Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works, Rattenbury ‘estimated’ that the new Parliament Buildings had utilized some 131,000 cubic feet of stone, more than double the 60,000 cubic feet that Frederick Adams had tendered upon in his contract of 1893.[83]

Although the body of Frederick Adams was never found and no death certificate ever issued, the insurers of his life paid the sum of $5000 to Sarah Adams in settlement of Adams’ policy.[84] Disaster was again to strike the family of Frederick Adams for, on May 26, 1896, the widow Sarah Adams, then aged 52, and son Frederick Adams Jr., then aged 26, and employed as a bricklayer on the new Parliament Buildings site, were both drowned in the collapse of the Point Ellice Bridge in Victoria, B.C.[85]

[1] The Yearbook of British Columbia, R.E. Gosnell, Librarian Legislative Assembly and Secretary Bureau Statistics. Victoria, BC 1897

[2] Victoria Daily Colonist, Victoria, B.C. June 21, 1892.

[3] https://www.leg.bc.ca/dyl/Pages/1893-Francis-M-Rattenbury.aspx

[4] BC Archives, GR 0054, Box 22, File 394.

[5] Annual Report of the Minister of Mines for the Year Ending 31st of December 1892. Page 547.

[6] B.C. Archives, CD 30.6/H11 and B.C. Legislature, Secessional Papers, Fourth session, Seventh Parliament, 1898. Page 818

[7] Ibid

[8] Ibid

[9] B.C. Archives, C/C/30.7/P23.1 F. Adams to CCLW, November 20, 1894.

[10] B.C. Archives, C/C/30.7/P23.1, File II, Contracts.

[11] BC Archives C/C/30.7/R18, Rattenbury to CCLW, December 1, 1893.

[12] B.C. Archives, CD 30.6/H11. CCLW to Adams, January 17,1894

[13] B.C. Archives, CD 30.6/H11, Macaulay to CCLW, January 21, 1894

[14] B.C. Archives, CD 30.6/H11, Memorandum of Agreement, February 1, 1894.

[15] The Stone Industries; Dimension Stone, Crushed Stone, Geology, Technology, Distribution, Utilization. Oliver Bowles. McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York, 1934.

[16] The Victoria Daily Colonist, Victoria, B.C. February 18 and 19, 1894.

[17] B.C. Archives – C/C/30.7/P23.1, Adams to Lubbe / Koksilah Quarry Co., February 22nd, 1894.

[18] B.C. Archives, GR 0013 – 06408, Order-in-Council 75, 27 February 1894

[19] B.C. Archives, C/C/30.7/P23.1, Adams to Lubbe / Koksilah Quarry Co., February 27th, 1894. Letter 1

[20] B.C. Archives, GR 0013 – 06408, Order-in-Council 75, 27 February 1894.

[21] BC Archives – C/C/30.7/P23.1, Adams to Lubbe / Koksilah Quarry Co., February 27, 1894. Letter 2

[22] BC Archives – C/C/30.7/P23.1 Answers to Mr. Lubbe’s statement by F.M. Rattenbury – “Architect,” Nov. 1894

[23] B.C. Archives, CD 30.6/H11 and B.C. Legislature, Secessional Papers, Fourth session, Seventh Parliament, 1898. Page 819

[24] Ibid

[25] Ibid

[26] B.C. Archives, CD 30.6/H11, Rattenbury to CCLW, April 24, 1894

[27] B.C. Archives, CD 30.6/H11, CCLW to Rudge, Huson & Gray. April 24, 1894

[28] B.C. Archives, CD 30.6/H11, CCLW to Rudge, Huson & Gray. June 12, 1894

[29] Archives, CD 30.6/H11, MEMORANDUM OF AGREEMENT – Adams, CCLW, and Huson, Rudge Gray. June 12, 1894

[30] BC Archives – C/C/30.7/P23.1, Adams to CCLW, November 20, 1894

[31] The Victoria Daily Times, Victoria, BC., May 16, 1894. Page 7

[32] The Victoria Daily Colonist, Victoria, B.C. May 19, 1894, Page 8

[33] The Victoria Daily Colonist, Victoria, B.C. May 31, 1894, Page 2

[34] The Victoria Daily Colonist, Victoria, B.C. June 21, 1894, Page 5

[35] The Victoria Daily Colonist, Victoria, B.C. June 26, 1894. Page 5

[36] B.C. Archives, CD 30.6/H11. Macaulay assigns Mortgage to GB Martin. November 1894

[37] BC Archives. C/C/30.7/P23.1.Theodore Davie, Attorney General’s Office to Adams. Nov. 15, 1894

[38] BC Archives. C/C/30.7/P23.1.Adams to the CCLW. November 20,1894

[39] BC Archives. C/C/30.7/P23.1.Rattenbury to CCLW. November 22 ,1894

[40] BC Archives – C/C/30.7/P23.1. CCLW to Adams. November 27, 1984

[41] B.C. Archives. C/C/30.7/P23.1. Adams to CCLW. November 27, 1894

[42] B.C. Archives. C/C/30.7/P23.1. Adams to CCLW. November 30, 1894.

[43] B.C. Archives. C/C/30.7/P23.1. Rattenbury to CCLW. December 3, 1894

[44] B.C. Archives. C/C/30.7/P23.1. Rattenbury to CCLW. December 6, 1894

[45] B.C. Archives. C/C/30.7/P23.1. Adams to CCLW. December 10, 1894

[46] The Victoria Daily Colonist, Victoria, B.C. December 11, 1894. Page 6

[47] BC Archives – C/C/30.7/P23.1. CCLW to Adams. December 11, 1984

[48] B.C. Archives. British Columbia Royal Commission pertaining to the payment of $30,000 to the legal representative of Frederick Adams. Evidence of Mr. John Turner. October 10, 1898

[49] Ibid

[50] B.C. Archives. C/C/30.7/P23.1. Adams to CCLW. December 13, 1894

[51] B.C. Archives. C/C/30.7/P23.1. Adams to CCLW. December 12, 1894

[52] Ibid

[53] B.C. Archives. British Columbia Royal Commission pertaining to the payment of $30,000 to the legal representative of Frederick Adams. Evidence of Mr. John Turner. October 10, 1898

[54] B.C. Archives. GR 0441, Box 3, File 4, Document 183. E. Mallandaine, Jr

[55] A Hearing Requested. The Victoria Daily Times, Victoria, BC. December 22, 1894. Page 4

[56] B.C. Archives. C/C/30.7/P23.1. Adams to CCLW. January 8, 1895

[57] The Parliament Buildings Muddle. The Victoria Daily Times, Victoria, BC February 4, 1895. Page 8

[58] Neither Money nor Food. The Victoria Daily Times, Victoria, BC February 6, 1895. Page 5

[59] Report of the Select Committee Appointed by the Provincial Legislature. The Victoria Daily Times, February 9, 1895. Page 7

[60] B.C. Archives. C/C/30.7/P23.1. Rattenbury to CCLW. January 18, 1895

[61] From the Provincial Legislature, extracts from the proceedings of the 53rd day Wednesday February 13, 1895. The Victoria Daily Times, Victoria, BC. February 14, 1895. Page 3

[62] From the Provincial Legislature, extracts from the proceedings of the 54th day Thursday, February 14, 1895. The Victoria Daily Times, Victoria, BC. February 15, 1895. Page 6 & 7

[63] B.C. Archives. C/C/30.7/P23.1. Rattenbury to CCLW. March 7, 1895

[64] Trouble at the Quarry. The Daily Colonist. Victoria, BC- Thursday, March 14, 1895, page 5

[65] Adams Assault Case. The Daily Colonist. Victoria, BC – March 21, 1895 – page 3

[66] BC Archives – C/C/30.7/P23.1. CCLW to Adams. March 20, 1895

[67] Sessional Papers, Second session, Seventh Parliament of the Province of British Columbia. 1896, Victoria. Page 937

[68] Ibid

[69] Ibid

[70] B.C. Archives, C/C/30.7/P23.1. Affidavit of Sarah Adams, Moses McGregor, George Jeeves, and James Baker. March 29, 1895

[71] B.C. Archives. C/C/30.7/P23.1. Original Contract No. 2 between F. Adams and the Government of British Columbia

[72] B.C. Archives. C/C/30.7/P23.1. Affidavit of Sarah Adams, Moses McGregor, George Jeeves, and James Baker. March 29, 1895

[73] Sessional Papers, Second session, Seventh Parliament of the Province of British Columbia. 1896, Victoria. Pages 937- 941

[74] Ibid

[75] The Daily Colonist. Victoria, BC. May 23, 1895

[76] B.C. Archives. GR0054, Box 26, File 432. Department of Public Works. Memo to Bank of B.C

[77] Sessional Papers, Second session, Seventh Parliament of the Province of British Columbia, Session 1896, Victoria, BC, Printed by Richard Wolfenden, Printer to the Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty, 1896.Page 355.

[78] The British Columbia Parliament Buildings, Edited by Martin Segger, Arcon, Vancouver, 1979

[79] B.C. Archives, GR 375, File 2, Evidence. Royal Commission on New Parliament Buildings

[80] B.C. Archives, GR 375, File 2, Exhibits. Rattenbury to CCLW, Dec 27, 1897. Royal Commission on New Parliament Buildings

[81] B.C. Archives, GR 375, File 2, Evidence. Statement of Hon. John Turner. Royal Commission on New Parliament Buildings

[82] Ibid

[83] B.C. Archives, C/C 30.7, H11, Rattenbury to CCLW. July 14, 1899

[84] The Daily Colonist. Victoria, BC June 16, 1895. Page 5

[85] The Daily Colonist. Victoria, BC. May 27, 1896