INDIAN PARTICIPATION IN THE GOLD DISCOVERIES

by: Thomas Arthur Rickard (Mining Engineer and Author)

The British Columbia Historical Quarterly Vol II, No. 1., January 1938

Numerous descriptions of the early gold discoveries in British Columbia have made the story familiar to those interested in the subject. No episode in the history of the American Northwest has been recounted so often because its romantic aspect has appealed irresistibly to our people. Nevertheless there remains an important feature of the gold rush in 1858 that has been overlooked, namely, the part played by the indigenes of the region, the Indians, and the discovery of the gold and in the mining operations that ensued.

The search for gold in our Province was incited by the successful exploitation of auriferous river-beds in California. The critical discovery, by James W Marshall, at Coloma, on January 24, 1848, caused a tremendous rush to the diggings along the western slope of the Sierra Nevada, and aroused the belief that other rich deposits of gravel might be found elsewhere in the region adjacent to the Pacific Coast. It is interesting, therefore, to note how the extensive occurrence of gold-bearing alluvium was signalized by successive discoveries that served to link the productive diggings at Coloma, on the South Fork of the American River, with those on the Thompson and Fraser Rivers in British Columbia. The first advance was to Oroville, on the Feather River, in 1848; then to Reading’s Bar on the Trinity River in 1849; next came Scott’s Bar on the Klamath in 1850. Gold was found in the sea-beach of Gold Bluff in the same year, and in the sand at the mouth of the Coquille River, in southern Oregon, in 1853. Meanwhile the diggings on Jackson Creek, also in Oregon, marked another step northward. In 1853 George McClellan found gold plentifully while engaged in surveying a military road in what is now northern Washington, through the Cascade Mountains from Walla Walla to Fort Steilacoom, on the coast near Admiralty Inlet. Gold was also discovered at that time during the exploration of a route for the Northern Pacific Railway, on the Similkameen River, which rises not far from Hope on the Fraser River, and joins the Okanogan at the International Boundary. Then, in 1855, gold was found by a “servant” of the Hudson’s Bay Company near Fort Colville[1], in the valley of the Columbia River, just south of the Canadian border.

James Cooper, testifying before the select committee on the Hudson’s Bay Company, in London, 1857, linked this discovery of gold at Fort Colville with the subsequent finding of it on Thompson’s River[2]. George M. Dawson, the distinguished Canadian geologist, was of the same opinion. Writing in 1889, he says: “it seems certain that the epoch-making discovery of gold in British Columbia, was the direct result of the Colville excitement. Indians from Thompson River, visiting a woman of their tribe who was married to a French-Canadian at Walla Walla, spread the report that the gold, like that found a Colville occurred also in their country, and in the summer or autumn of 1857, four or five Canadians and half breeds crossed over to the Thompson, and succeeded in finding workable places at Nicoamen, on that river, 9 miles above its mouth. On the return of these prospectors, the news of the discovery of gold spread rapidly.[3]“

Thus it is evident that information derived from the Indians lured the prospectors northward into British Columbia; but before proceeding with the sequential story of gold discovery in our Province it must be noted that an unheralded find the gold was made by the famous botanist, David Douglas, at a date long precedent to the epochal discoveries in California and Australia, in 1848 and 1851, respectively. Capt. W. Colquhoun Grant, of Sooke, in a paper presented to the Royal Geographical Society in 1859, says: “there can be little doubt that it (gold) exists in the mountains of New Caledonia, to the northward of where men are now looking for it, and also a little to the southward, where several years ago David Douglass (sic), the eminent botanist, found enough whereof to make a seal. This occurred on the shores of Lake Okanogan…[4].” No doubt the discovery was made at the mouth of the creek as it entered the lake. Douglas was there in 1833[5]. He was killed in July 1834, when in the Hawaiian Islands, and, as he did not go to England during the interval, no word of the discovery reached the outside world. At that date, moreover, even to a scientist such as Douglass, the finding of gold would not suggest the portentous consequences that might ensue from the successful development of profitable mines. The same inability to foresee such consequences was shown by officials in California and Australia when the finding of gold was made known in those regions several years before the discoveries that started the world-wide stampedes to the diggings.

The earliest gold discovery in British Columbia that aroused public interest was made by an Indian on one of the Queen Charlotte Islands. Richard Blanshard, the first Governor of Vancouver Island, reported to Earl Grey, the Colonial Secretary, in August 1850, that he had seen “a very rich specimen of gold ore, said to have been brought by the Indians of Queen Charlotte’s island.[6]” In the following year, 1851, an Indian woman found a nugget on the beach of Moresby Island. After a part of it had been cut off, it was taken to Fort Simpson, where it passed by trade into the hands of the Hudson’s Bay factor at that place. The nugget, as received, weighed about 5 ounces. Later it was sent to the headquarters of the Hudson’s Bay Company at Fort Victoria. On March 29, 1851, Gov. Blanshard informed Earl Grey: “I have heard that fresh specimens of gold have been obtained from the Queen Charlotte Islanders; I have not seen them myself, but they are reported to be very rich.[7]” The Hudson’s Bay Company sent the ship Huron to Mitchell Harbor for the purpose of investigation. Some gold-quartz was brought back to Fort Victoria and stimulated further interest in the discovery. In July and again in October 1851, the brigantine Una was sent thither by the Hudson’s Bay Company and returned with information concerning a quartz vein that was 7 inches wide and traceable for 80 feet. It was reported to contain “25% of gold in some places,[8]” which indicated specimen stuff, goodly to look upon. Some of the quartz was blasted and then shipped, despite the interference of the Indians. The Una was lost on her return voyage. Then the Orbit, an American ship, which was on the rocks off Esquimalt, was bought by the Company, repaired, and renamed the Recovery. She was sent north with 30 miners in addition to her crew, these miners having agreed to share their luck. Three months were spent in getting a cargo of ore, which was taken to England and eventually yielded a sum of money giving the miners $30 per month for their labour.

When these facts were noised abroad, not only at Fort Victoria but at San Francisco, several vessels sailed from that California Port for Mitchell Harbor. The deposit had been nearly exhausted, and the Americans soon left, disappointed. Later the American ship Susan Sturges arrived, and the captain collected some of the ore discarded by the Una expedition. A second voyage by the same ship ended in disaster, for she was captured, and the crew made prisoners by the Indians at Masset, on Graham Island. The American gold seekers were rescued by a party sent thither on the Hudson’s Bay Company steamer Beaver. Altogether about $20,000 was taken from the little quartz vein at Mitchell Harbor, known also as Gold Harbor and Mitchell Inlet.[9]

We have seen how soon the miniature rush to these northern islands came to a dismal end, because but little gold was found and the occurrence of the precious metal proved to be extremely patchy; nevertheless, the event is of historic importance because it made a few people then on our Western coast aware of the possibility of developing profitable mines. It made them gold conscious. Moreover, it was the means of establishing an important precedent, for, in 1853, James Douglas, the second Gov. of Vancouver Island, asserted the regalian right to any gold deposits that might be discovered. This action on his part proved deeply significant.

The regalian right, or Royal claim, to deposits of precious metal is traditional; it is a kingly perquisite that comes from the days of the Roman emperors. In the 16th century the Spanish King’s share was fixed at 1/5 of the gold or silver obtained by his subjects, chiefly in Mexico and Peru. In England, the doctrine offodinae regales, or mines royal, was revived by Henri III, (1216 – 1272) and was well established in the reign of Queen Elizabeth. It is sustained by Blackstone in his Commentaries, under date of 1765[10]. In modern days, the regalian right was asserted when gold was discovered in Australia and was therefore well fortified by precedent when invoked by Governor Douglas.

At that time James Douglas had become the Governor of Vancouver Island while still the Chief Factor, at Victoria, of the Hudson’s Bay Company. The proclamation in 1853, which asserted the rights of the Crown and exacted a license fee from the gold miners, was instigated by Sir John Pakington, the Colonial Secretary in London. He, in September 1852, instructed Douglas “to take immediate steps for the protection of British interests against the depredations of Indians, or the unwarranted intrusions of foreigners, on the territory of the Queen,[11]” and forthwith issued a commission making Douglas Lieutenant-Governor of the Queen Charlotte Islands. Whereupon, in March 1853, Governor Douglas issued a proclamation asserting the right of the Crown to any gold found in “The Colony of Queen Charlotte’s Island,” and followed this action in April by fixing a miners license fee of 10 shillings per month, payable in advance, and to be obtained only at Fort Victoria.

We may note that the earliest gold to come within the cognizance of the Hudson’s Bay officers was brought to them by the Indians. This is not surprising. Gold was usually the first metal to become known to primitive man. He saw the shining substance on the edge of riverbeds that were his highways through the wilderness. Gold does not corrode or tarnish, it is beautiful, and it is so soft as readily to be shaped by hammering with a stone. Primitive man at an early stage of his existence began to use the metal for making ornaments, such as earplugs and bangles. When the European came among the Indians on our Western coast, he wore rings and watch chains, his women wore earrings and bracelets, all made of gold; the natives therefore saw readily that the white people set a high value on gold, and they inferred correctly that if they brought it to the trader he would be willing to barter his goods for the precious metal. This led the Indians to search for it and bring it to the Hudson’s Bay Company’s post. Moreover, the natives resented the trespass upon their domain, strange as it may seem to some people, and annoyed the gold seekers that came to the Queen Charlotte discovery; they stole the tools of the miners, and the gold as well. Chief Trader W. H. McNeill, who accompanied the Una expedition, reported to Douglas:

“I am sorry to inform you that we were obliged to leave off blasting, and quit the place for Fort Simpson, on account of the annoyance we experienced from the natives. They arrived in large numbers, say 30 canoes, and were much pleased to see us on our first arrival. When they saw us blasting and turning out the gold in such large quantities, they became excited and commenced depredations upon us, stealing the tools, and taking at least one half of the gold that was thrown out by the blast. They would lie concealed until the report was heard, and then make a rush for the gold; a regular scramble between them and our men would then take place; they would take our men by the legs, and hold them away from the gold. Some blows were struck on these occasions. The Indians drew their knives on our men often. The men who were at work at the vein became completely tired and disgusted at their proceedings, and came to me on three different occasions and told me they would not remain any longer to work the gold; that their time was lost to them, as the natives took one half of the gold thrown out by the blast, and blood would be shed if they continued to work at the digging; that our force was not strong or large enough to work and fight also. They were aware they could not work on shore after hostility commenced, therefore I made up my mind to leave the place and proceed to this place (Fort Simpson).

The natives were very jealous of us when they saw that we could obtain gold by blasting; they had no idea that so much could be found below the surface; they said that it was not good that we should take all the gold away; if we did so, they would not have anything to trade with other vessels should any arrive. In fact, they told us to be off.[12]“

McNeill had with him only 11 men, a force much too small to discipline the Indians; moreover, it was the policy of the Hudson’s Bay Company not to antagonize natives, with whom they traded for furs. Therefore, any sort of lethal contest was avoided.

The discoveries of gold on the mainland, like the one made on Moresby Island, must be credited to the Indians; it was they, and not any canny Scot or enterprising American, that first found the gold on the Thompson or Fraser Rivers, or first proceeded to gather it for the purpose of trade. The Hudson’s Bay agent at Kamloops, on the Thompson River, obtain gold dust from the Indians as early as 1852, and similar gold came, in the course of trade with the natives, to other posts of the fur company. In the records of the fur trade, as kept at Fort Victoria, it is stated that 3 3/4 ounces of gold were included in the takings at Fort Kamloops in 1856.[13] “Gold,” says Douglas in his memoranda under the date of 1860, “was first found on Thompson’s River by an Indian, 1/4 of a mile below Nicoamen. He is since dead. The Indian was taking a drink out of the river. Having no vessel, he was quaffing from the stream when he perceived a shiny pebble which he picked up and it proved to be gold. The whole tribe forthwith began to collect the glittering metal.[14]” This probably was in 1852. Roderick Finlayson, Chief Factor at Fort Victoria, says that gold was discovered by the Indians in crevices of the rocks on the banks of the Thompson. Donald McLean, the trader in charge at Kamloops, inspected the gold bearing ground and then sent down to Victoria for some iron spoons to be used by the Indians for the purpose of extracting the nuggets from the crevices in the rocky beds of the creeks. The spoons were sent, as requested, and McLean was instructed to encourage the natives in searching for gold and using it for trade.[15]

News of the important discovery at Colville reached Douglas in the spring of 1856. He was not at all secretive about the finding of gold, and on April 16 reported to the Colonial Secretary as follows: “I hasten to communicate for the information of her Majesty’s Government a discovery of much importance made known to me by Mr. Angus McDonald, Clerk in charge of Fort Colville, one of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s trading posts on the Upper Columbia District. That gentleman reports, in a letter dated on 1 March last, the gold has been found in considerable quantities within the British territory, on the Upper Columbia, and that he is moreover of opinion that valuable deposits of gold will be found in in many other parts of the country; he also states that the daily earnings of persons employed in digging gold ranging from 2 £ to 8 £ ($10-$40) for each man. … Several interesting experiments in gold washing have been lately made in this colony, with a degree of success that will no doubt lead to further attempts for the discovery of the precious metal.[16]” In October, 1856, Douglas reported further that the extent of the gold deposits was as yet undetermined, but that he took a sanguine view of their possible value. The amount of gold produced was not known, but some 220 ounces had been received at Victoria from the Upper Columbia.[17]

Definite information was still lacking in the summer of 1857; but by that date mining operations on the Thompson River, as on the Queen Charlotte Islands, had led to friction with the Indians. In a dispatch to the Colonial Secretary dated July 15, 1857, Douglas reports:

“A new element of difficulty in exploring the gold country has been interposed through the opposition of the native Indian tribes of Thompson’s River, who have lately taken the high-handed, though probably not unwise course, of expelling all the parties of gold diggers, comprised chiefly of persons from the American territories, who had forced an entrance into their country. They have also openly expressed a determination to resist all attempts at working gold in any of the streams flowing into Thompson’s River, both from a desire to monopolize the precious metal for their own benefit, and from a well-founded impression that the shoals of salmon which annually ascend these rivers and furnish the principal food of the inhabitants, will be driven off, and prevented from making their annual migrations from the sea[18].”

Later dispatches indicate that for a considerable time the Indians retained a virtual mining monopoly in the Couteau, or Thompson River region. Thus, on December 29, 1857, Douglas described conditions, as reported to him by correspondents resident there, as follows:

“It appears from their reports that the auriferous character of the country is becoming daily more extensively developed, through the exertions of the native Indian tribes, who , having tasted the sweets of gold finding, are devoting much of their time and attention to that pursuit.

They are, however, are present almost destitute of tools for moving the soil, and of washing implements for separating the gold from the earthly matrix, and have therefore to pick it out with knives, or to use their fingers for that purpose; a circumstance which accounts for the small products of gold up to the present time, the exports being only about 300 ounces since the 6th of last October.[19]”

Even in the spring of 1858 white miners were few and far between; and on April 6 Douglas reported at some length upon this aspect of the situation:

“The search for gold and “prospecting” of the country, had, up to the last dates from the interior, been carried on almost exclusively by the native Indian population, who have discovered the productive beds, and put out almost all the gold, about eight hundred ounces, which has been hitherto exported from the country, and who are moreover extremely jealous of the whites, and strongly opposed to their digging the soil for gold.

The few white men who passed the winter at the diggings, chiefly retired servants of the Hudson’s Bay company, though well acquainted with Indian character, were obstructed by the natives in all their attempts to search for gold. They were on all occasions narrowly watched, and in every instance when they did succeed in removing the surface and excavating to the depth of the auriferous stratum, they were quickly hustled and crowded by the natives, who, having by that means obtained possession of the spot, then proceeded to reap the fruits of their labours.

Such conduct was unwarrantable and exceedingly trying to the temper of spirited men, but the savages were far too numerous for resistance, and they had to submit to their dictation. It is, however, worthy of remark, and a circumstance highly honourable to the character of those savages, that they have on all occasions scrupulously respected the persons and property of their white visitors, at the same time that they have expressed a determination to reserve the gold for their own benefit.[20]

Douglas was well aware that this state of affairs could not continue. Already, on December 29, he had warned the Colonial Secretary that a rush to the diggings was impending:

“The reputed wealth of the Couteau mines is causing much excitement among the population of he United States territories of Washington and Oregon, and I have no doubt that a great number of people from those territories will be attracted thither with the return of the fine weather in spring.[21]

The menace inherent in this coming stampede was twofold. In the first place, it was obvious that most of the miners would be Americans, and their arrival might well threaten British sovereignty over what is now the southern mainland of British Columbia. In the second place, Douglas was convinced that, in the event of a sudden influx of miners, “difficulties between the natives and whites” would occur frequently, and that, unless preventive measures were taken, the country would “soon become the scene of lawless misrule.”[22]

The manner in which Douglas warded off the first danger need not be considered in detail. It is sufficient to record that he acted promptly, and in December, 1857, issued a proclamation and accompanying regulations, in his capacity as Governor of Vancouver Island, which declared “all mines of gold, and all gold in its natural place of deposit, within the district of Fraser’s River and of Thompson’s River” to be the property of the Crown, and imposing a license fee of ten shillings per month, payable in advance, upon all gold-miners. The wording of this proclamation follows closely upon the text of that issued by Douglas in 1853, and the time of the Queen Charlotte Islands excitement; and it is clear that he regarded the first proclamation, which had met with approval in London, as indicative of the policy that the authorities would expect him to follow when an analogous situation arose on the mainland. Owing to the fact that Douglas had no legal jurisdiction over the mainland until late in 1858, and other circumstances, certain of his acts and declarations were disallowed by the Colonial Office; but there doubt that his prompt assumption of authority on behalf of the Crown, as well as the Hudson’s Bay Company, was chiefly responsible for the fact that the question of sovereignty never became a serious issue.

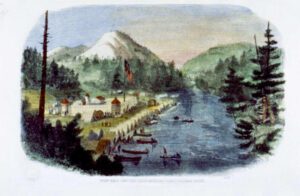

On April 25, the steamship Commodore arrived in Victoria with 450 miners aboard. The overwhelming character of the immigration which followed will be appreciated when it is stated that with the arrival of her passengers the white population of Vancouver Island almost doubled. Scores of ships followed in the wake of the Commodore, and it is estimated that as many as 30,000 persons flocked to the Fraser River mines during the late spring and early summer of 1858.

In the latter part of May, before this immigration reached its peak, Douglas paid a visit to the gold diggings in the vicinity of Hope and Yale, the district to which the majority of newcomers had gone. His diary of the journey has survived, and many entries therein refer to the mining activities of the Indians, and the possibility of trouble between them and the white miners. Amongst other news, Douglas notes that he is informed from Fort Hope that “the Indians are getting plenty of gold and trading with the Americans.” That means they were bartering their gold, probably for tobacco, with the newcomers. The same information stated that “Indian wages are from three to four dollars a day.” This indicates that the natives were employed by the American miners. The same thing happened in the early operations on the American River in California, where also the Indians were employed by the diggers. At Hill’s Bar, on the Fraser, Douglas was informed that “80 Indians and 30 white men are employed. It is impossible (for the Hudson’s Bay Company) to get Indian labour at present, as they are all busy mining, and make between two and three dollars a day each man.”[23]

It was at Hill’s Bar, too, that Douglas became aware of dangerous friction between the Indians and whites, as he had all along anticipated would result from the gold-rush. The Americans, who had suffered from Indian attacks when crossing the plains to California, were inclined to think that the only good Indian was a dead one. They had fought with the natives when coming northward through the Oregon country, and they had therefore no patience with the Indian desire to monopolize the gathering of gold. Naturally they were overbearing in their attitude to the natives, who, in return, resented their aggression, and resented also their maltreatment of the squaws.

In a dispatch to the Colonial Secretary dated June 15, 1858, Douglas describes the conflict, and the steps he had taken to deal with it as follows:

“On the arrival of our party at “Hills Bar,” the white miners were in a state of great alarm on account of a serious affray which had just occurred with the native Indians, who mustered under arms in a tumultuous manner, and threatened to make a clean sweep of the miners assembled there.

The quarrel arose out of a series of provocations on both sides, and from the jealousy of the savages, who naturally felt annoyed at the large quantities of gold taken from their country by the white men.

I lectured them soundly about their conduct on that occasion, and took the leader in the affray, an Indian highly connected in their way, and of great influence, resolution, and energy of character, into the Government service, and found him exceedingly useful in settling other Indian difficulties.”

Douglas “also spoke with great plainness of speech to the white miners” and warned them “that no abuses would be tolerated; and that the laws would protect the rights of the Indian, no less than those of the white man.”[24] Some sort of order was restored, but Douglas returned to Victoria in a pessimistic mood, due in part to the news that a detachment of United States troops had been defeated by the Indians in Oregon. This victory had “greatly increased the natural audacity of the savage, and the difficulty of managing them,” and he feared that it would require “the nicest tact to avoid a disastrous Indian war.”[25]

He was correct in his opinion that the Indian problem was not yet resolved. Friction with the white miners continued; and a German traveller mentions the interference of the Indians as noted by him near the junction of the Fraser and Thompson, somewhat later in 1858:

“When …. a few adventurers from Oregon went into the District of Great Forks and began washing gold, the Couteau Indians, who lived in the vicinity, soon followed their example. But when larger numbers of gold miners arrived in the land in 1858 trouble began between the natives and the new arrivals. The Indians took their tools away from the newly arrived miners declaring that they would not permit any further invasion of their country; but the newcomers streamed into the country in such numbers that there could be no longer any question of resistance.”[26]

It was too much to expect that this change from Indian to white domination would be entirely peaceful. In the Fraser Canyon region tension rose in July, as the number of miners and others crowding the diggings reached its peak, and August saw the outbreak of actual hostilities. Numerous small affrays had occurred previously; but on the 14th a pitched battle took place near Boston Bar in which about 150 whites participated. At least seven Indians were killed, and the natives were completely routed. It is significant that the letter which brought this news to Victoria criticized the Government severely. “It is very singular, “the writer observed, “that after Gov. Douglas has taken from each miner five dollars for a license, he does not give those paying it the least protection.”[27] In actual fact, causes beyond Douglas’s control, at least for the time being, were aggravating the situation. For one thing, an age-old hostility separated the Indians dwelling below the canyon of the Fraser from those above it; and when the white miners sought to ascend the river the Indians tried to stop them, and several fights ensued. Moreover, the difficulty of maintaining good relations with the Indians when “ardent spirits” were sold to them by certain of the diggers. On July 27, a public meeting held at Fort Yale voted to prohibit the sale of spirituous liquors to the Indians, but this was more easily said than done. In addition, the Chinese were accused of being in league with the natives and supplying them with arms and ammunition.[28]

The progress of events can be traced in the columns of the Victoria Gazette. By the middle of the month it was estimated that 500 miners had deserted their diggings above the canyon and descended the river to Yale and Hope, where they felt secure against attack from the Indians. On August 17, Captain H. M. Snyder organized a punitive force of 167 men, all well armed, and started up the Fraser from Yale. He was prepared to fight if necessary but hoped that a resolute display of force would suffice to bring the natives to terms. This proved to be the case, and, thanks to his moderation, the advance to the junction of the Fraser and Thompson, where he arrived on August 22, was marked by a series of parleys and peace treaties with the natives instead of the bloody battle that might easily have ensued. Meanwhile, in his absence, and before the fate of his expedition was known down the river, an appeal was sent to Governor Douglas by the residents of Fort Hope, begging him to take steps to maintain order in the mining district. At Victoria, the force of this appeal was increased tenfold by a report, circulated on August 25, that 42 miners had been massacred by the Indians. It was known within 24 hours that the rumour was untrue, and that only two men had been killed; but Douglas left for the mainland on August 29, accompanied by the only military force he could muster, which consisted of 35 sappers and the marines recruited from the troops accompanying the Boundary Commission and from H. M. S. Satellite.

Douglas arrived at Hope on September 1. Captain Snyder had returned to Yale on August 25, and all was quiet in the Fraser Canyon region. The pausing of hostilities might well have been only momentary, however, and Douglas set about placing it upon a permanent basis. His report to the Colonial Secretary, dated October 12, is illuminating:

“My first attention was devoted to the state of the Indian population. I found them much incensed against the miners; heard all their complaints and was irresistibly led to the conclusion that the improper use of spirituous liquors had caused many of the evils complained of.

I thereupon issued a proclamation, of which I have transmitted a copy, warning all persons against the practice, and declaring the sale or gift of spirituous liquors to Indians a penal offence, and I feel satisfied that the rigid enforcement of the proclamation will be of great advantage both to the whites and the Indians.

I also received at Fort Hope visits from the Chiefs of Thompson’s River, to whom I communicated the wishes of Her Majesty’s Government on their behalf, and gave them much useful advice for their guidance in the altered state of the country. I also distributed presents of clothing to the principal men as a token of regard.[29]

More interesting, because it shows the consideration with which Douglas treated the Indians, is the following paragraph, descriptive of his parley with the natives at Hope:

“The Indians were assembled and made no secret of their dislike to their white visitors. They had many complaints of maltreatment, and in all cases where redress was possible it was granted without delay. One small party of those natives laid claim to a particular part of the river, which they wish to be reserved for their own purposes, a request which was immediately granted, the space staked off, and the miners were taking claims there were immediately removed, and public notice given that the place was reserved for the Indians, and that no one would be allowed to occupy it without their consent.”[30]

Undoubtedly there were two sides to the controversy; and an American pointed this out, indicating several of the grievances suffered by the Indians, in a letter written to the Victoria Gazette from Yale, several days before Douglas arrived there.[31]

The settlement made between Douglas and the Indians in September 1858, virtually ended the threat of war between the natives and the miners. Isolated clashes and murders did occur thereafter, but for the most part peace and a new sense of security reigned on the Fraser. Difficulty with the Indians continued to a somewhat later date on what is known as the Harrison-Lillooet route to the upper Fraser and Thompson. The contemporary letter from C. C. Gardiner describes the manner in which he and his comrades were robbed and bullied by the natives near Anderson Lake, 1858.[32] Items in the newspapers show that trouble was still experienced by travellers there even at the end of the year; but here, as on the Fraser, danger of a serious clash decreased rapidly.

There were a number of reasons for the coming of peace. In the first place, the Indians saw that the whites had come to stay, and realized that they had become too numerous and well entrenched to be dislodged even temporarily, let alone to be driven from the country. Secondly, the Crown Colony of British Columbia was formally proclaimed in November, with Douglas as Governor, and the new government, though still consisting a little more than a skeleton crew of magistrates and gold commissioners, was nevertheless making its authority felt. This authority was greatly strengthened at the end of the year by the arrival of a detachment of Royal Engineers under the command of Colonel Moody. It is probable, too, that the pressure of the whites upon the Indians decreased after the month of September in a number of ways, owing to the fact that many disappointed miners left the country.

There can be no possible doubt, however, that the dominant influence was the character and ability of Governor Douglas. The American miners, and Captain Snyder in particular, deserve commendation for their moderation; but it seems obvious that their attitude was determined to a large extent by the law-abiding and orderly atmosphere which Douglas, in spite of the slender resources at his command when the rush to the mines commenced, somehow managed from the first to create upon the mainland. Quite as significant was the fact that he had risen to a post of high responsibility in the service of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Legally, Douglas may have exceeded his powers upon occasion, and the controversy as to whether he placed the service of the Crown below or above that of the Company will doubtless be revived from generation to generation. But even the barest outline of the part played by the Indians in the gold rush, such as it has been possible to give in this paper, makes it clear that it was a happy circumstance for Crown and Company alike that, when the great immigration of 1858 swept up the Fraser, a man with his great knowledge of Indian character, and long experience in dealing with the natives, was responsible for the administration of the country.

- A. Rickard.

Victoria, BC.

[1] Formerly spelled Colvile, after Andrew Colvile, a Governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

[2] Report from the Select Committee on the Hudson’s Bay Company, London, 1857,pp. 205, 207.

[3] George M Dawson: The Mineral Wealth of British Columbia, Montréal, 1889, p 18 R (Geological Survey of Canada).

[4] W. C. Grant: “remarks on Vancouver Island,” Journal of the Royal Geographic Society, XXXI, (1861),p 213.

[5] Oregon Historical Quarterly, VI (1905),p 309

[6] Correspondence relative to the Discovery of Gold in Queen Charlotte’s Island, London, 1853. p 1. (Cited hereafter as Queen Charlotte’s Island papers.)

[7] Ibid

[8] Dawson, op cit, p 17R

[9] Ibid., p 18R

[10] T. A. Rickard: Man and Metals, New York, 1932 pp 606, 617

[11] Queen Charlotte’s Island Papers, p13.

[12] Ibid, second series, London, 1853, p8

[13] Columbia District and New Caledonia Trade Returns (MS in Archives of BC).

[14] James Douglas; Private Papers, p 78 (transcript in Archives of BC).

[15] Rodrick Finlayson; History of Vancouver Island and the Northwest Coast, p 43 (transcript in Archives of BC).

[16] Correspondence relative to the Discovery of Gold in the Fraser’s River District, London, 1858, p 5 (Cited hereafter as Gold Discovery Papers.)

[17] Ibid, p 6

[18] Ibid p 7

[19] Ibid, p 8

[20] Ibid, p 10.

[21] Ibid, p 8.

[22] Ibid

[23] Private Papers, First Series, p 58.

[24] Papers relative to the Affairs of British Columbia, Part I, London, 1859, p 16.

[25] Ibid, p 17

[26] Dr. Carl Freisach: Excursion through British Columbia, 1858, Graz. 1875. This quotation is from a manuscript English translation in the library of Dr. R.L Reid, who also processes a copy of the book.

[27] Victoria Gazette, August 24, 1858.

[28] Ibid, August 4 and 10

[29] Papers relative to the Affairs of British Columbia, Part II, London, 1859,p 4

[30] Ibid p 5

[31] Victoria Gazette, September 1, 1858. On the general course of events see ibid., 24, 25, what he six, 31; September 3, seven, 14, 16, and 28, 1858.

[32] British Columbia Historical Quarterly, I (1937), pp 250, 251.