British Columbia Historical Quarterly: Vol. 07 (VII) No.1

January 1943.

Gilbert Norman Tucker

Department of the Naval Service

Ottawa,

The Career of H.M.C.S. “Rainbow”.

“Now the gallant Rainbow she rowes upon the sea,

Five hundred gallant seamen to bear her company.”

Anonymous Ballad.

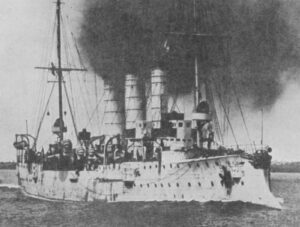

With the creation of a Canadian naval service in 1910, a need for training ships at once arose. To meet this need the Canadian government bought from the British Admiralty the obsolescent cruisers H.M.S. Niobe and H.M.S. Rainbow. An old warship makes an admirable training-vessel, and on these two ships officers and men were to be trained for the five cruisers and six destroyers which it was intended to build. The Niobe was to be stationed on the east coast and he much smaller Rainbow at Esquimalt. For the latter, a light cruiser of the Apollo class, the Government paid $50,000. A ship of the Royal Navy often has many predecessors of the same name, and on the Rainbow’s hand steering-wheel were inscribed the names and dates of actions in which earlier Rainbows had taken part: “Spanish Armada 1588 – Cadis 1596 – Brest 1599 – Lowestoft 1665 – North Foreland 1666 – Lagos Bay – 1759 – Frigate Hancock 1777 – Frigate Hebe 1777.”

The Rainbow was commissioned as a ship of the Royal Canadian Navy at Portsmouth on August 4, 1910, and was manned by a nucleus crew supplied by the Royal Navy and the Royal Fleet Reserve. The Royal Navy personnel were entered on loan for a period of two years, while the Fleet Reservists were enrolled in the Royal Canadian Navy under special service engagements of two to five years. On August 8 the Rainbow, which was in charge of Commander J.D.D. Stewart, received her sailing orders – the first instructions ever given to a warship by the Canadian naval authorities[1]. She left Portsmouth on August 20 for Esquimalt, sailing around South America by way of the Straits of Magellan, a distance of about 15,000 nautical miles. At the equator “Father Neptune” came aboard wearing a crown of gilded papier-mãché, attended by his courtiers and his bears, and performed his judicial duties in the time-honoured way.

Near Callao the German cruiser Breman was seen carrying out heavy-gun firing practice at a moored target, and at the end of the cruise Commander Stewart reported on what had been observed of this practice firing. The Admiralty knew very little, at this time, about the German Navy’s methods of gunnery practice.[2] Naval Headquarters in Ottawa immediately asked Commander Stewart for further particulars; but these he was unable to supply. On the morning of November 7, 1910, the Rainbow arrived at Esquimalt, which was to be her home thenceforth. Among the ships in port when she arrived were two – H.M.S. Shearwater and the Grand Trunk Pacific steamer Prince George – with whom she was to be closely associated four years later. Having saluted the country with twenty-one guns, the Rainbow dressed ship and prepared the receive distinguished visitors. [3]

“History was made at Esquimalt yesterday, “wrote a reporter for the Victoria Colonist of the following day. “H.M.C.S. Rainbow came: and a new navy was born. Canada’s blue ensign flies for the first time on the Dominion’s own fighting ship in the Pacific – the ocean of the future where some of the world’s greatest problems will have to be worked out. Esquimalt began its recrudescence, the revival of its former glories.”[4] The Victoria Times reported that “nothing but the most favorable comment was heard on the trim little cruiser.” The same newspaper stated in an editorial that: –

We are pleased to welcome His Majesty’s Canadian ship Rainbow to our port today. We are told in ancient literature that the first Rainbow was set int eh sky as a promise of things to come. So it may be with His Majesty’s ship. She is a training craft only, but she is the first fruits on this coast of the Canadian naval policy, the necessary forerunner of eh larger vessels which will add dignity to our name and prestige to our actions.[5]

According to the Colonist:–

“The event was one calculated to awaken thought in the minds of all who endeavored to grasp its true significance. The Rainbow is not a fighting ship, but she is manned by fighting men, and her mission is to train men so as to make them more fit to defend our country from invasion, protect our commerce on the seas and maintain the dignity of the Empire everywhere. Her coming is a proof that Canada has accepted a new responsibility in the discharge of which, new burdens will have to be assumed. On this Western Frontier of Empire, it is all important that there shall be a naval establishment that will count for something in an hour of stress”.[6]

Early in the following month the Rainbow visited Vancouver, where the mayor and citizens extended a warm welcome. Soon after her arrival on the coast the cruiser was placed on training duty and recruits were sought and obtained on shore, twenty-three joining up during the ship’s first visit to Vancouver.[7] On March 13, 1911, the Lieutenant-Governor and the Premier of British Columbia presented the ship with a set of plate, the gift of the Province. During the next year and a half the Rainbow made cruises up the coast, calling at various ports where she was in great request for ceremonies of all sorts. During some of these cruises, training was combined with fishery patrol work, which chiefly consisted in seeing that American fishermen did not fish inside the 3-mile limit.

Meanwhile the policy of developing an effective Dominion navy was allowed to lapse. The Borden Government, which came to power in 1911, was unwilling to proceed with Laurier’s policy, of which it disapproved, and unable to carry out its own. In the summer of 1912 many of the borrowed Royal navy ratings returned to Britain and were not replaced; nor di more than a few Canadian officers or men come forward to join a service which seemed to be rooted precariously in stony ground. The following table[8] which gives the number of cadets who entered the Navy, the number of Royal Canadian Naval officers and ratings on strength, and the naval expenditures, in each of four years, tells the story:-

Year | Number of Cadets entering the R.C.N. | Number of R.C.N. Officers and Ratings | Naval Expenditure |

1910-11 | 28 | 704 | $1,790,017 |

1911-12 | 10 | 695 | 1,233, 456 |

1912-13 | 9 | 592 | 1,085,660 |

1913-14 | 4 | 330 | 597,566 |

Accordingly, during the two years immediately preceding the first Great War, the Rainbow lay at Esquimalt with a shrunken compliment, engages in harbor training, except when an occasional short cruise was undertaken for the sake of her engines.

On July 7, 1911, a Convention had been signed by Russia, Japan, the United States, and Great Britain, which prohibited pelagic sealing in the Pacific north of a certain line. The purpose of this agreement was to prevent the indiscriminate slaughter which was inevitable if seals were hunted at sea. Before as well as after 1911 British warships had kept an eye on the seal-fisheries, and for several years prior to the first great War this work had been done by the sloops Algerine and Shearwater. During the summer of 1914 these vessels were doing duties on the Mexican coast: the Canadian Government had therefore decided to send the Rainbow on sealing patrol, and on July 9 she was ordered to prepare for a three-months cruise. Her extremely slender crew was strengthened by a detachment from England, another from Niobe, and by volunteers from Vancouver and Victoria. She was dry-docked for cleaning and replenished with stores and fuel.

In May, 1914, the steamer Komagata Maru reached Canada, carrying nearly 400 passengers, natives of India who were would-be immigrants. When they found their entry barred by certain Dominion regulations the Indians refused to leave Vancouver harbour, and staying on and on, their food supplies ran low. On July 18, 175 local police and other officials tried to board the Komagata Maru, so as to take the Indians off by force and put them aboard the empress of India for passage to Hong Kong. A storm of missiles which included lumps of coal greeted the police, who thereupon steamed away without having used their firearms.[9]

By this time the Rainbow was in a condition to intervene. The Naval Service Act contained no provision for naval aid to the civil power; nevertheless on July 19 the Rainbow’s commander was instructed to ask the authorities in Vancouver whether or not they wanted his assistance, and the next day he reported that: “Rainbow can be ready to ;leave for Vancouver ten o’clock tonight …..immigration agent for Vancouver and crown officers very anxious for Rainbow …..”[10] the cruiser was ordered to proceed to Vancouver and render all possible assistance, while the militia authorities were instructed to co-operate with her in every way.[11] She left Esquimalt that night taking a detachment of artillery with her and reached Vancouver next morning. Meanwhile the Indians had laid hands on the Japanese captain of the Komagata Maru in an attempt to seize his vessel. The warship’s presence had the desired effect, however, without the use of violence: the Indians agreed to leave, and were given a large consignment of food, a pilot was supplied from the Rainbow, and on July 28 the Komagata Maru sailed for Hong Kong. The cruiser saw her safely off the premises, accompanying her out of through the Strait of Juan de Fuca as far as the open sea, and then returned to Esquimalt.

In the summer of 1914, when tension developed into crisis, and crisis into war, the Admiralty’s problems off the west coast was a three-fold one. First of all there was the coast of British Columbia to protect. The greater part of it was unrewarding to a raider. It offered several inviting objectives, however, of which Vancouver and Nanaimo were difficult to get at; while Victoria, Esquimalt, and Prince Rupert were more or less exposed. In the second place, shipping had to be guarded. The coastwise trade received some protection from the configuration of that extraordinary seaboard, and the fishing-boats were unlikely to invite a serious attack. The Strait of Juan de Fuca with its approaches, however, formed a focal area where the ships on two important ocean routes converged. The routes were those from Vancouver to the Orient and from Vancouver to Great Britain. The ships on the former run were mainly fast liners, and were well protected by the immense size of the ocean on which they sailed, except on the terminal waters. The ships sailing for Great Britain, carrying for the most part grain, lumber, and canned salmon, took their cargoes southward down the coast and around by the Strait of Magellan, or passed them by rail across the Isthmus of Panama. This traffic lane was a tempting one for commerce-raiders, because, running along the coast as it did, merchantmen using it would be easy to find, while the raider operating along it could remain close to possible sources of fuel and of information. Moreover, in addition to receiving the trade to and from Vancouver, this route was fed by the principal Pacific ports of the United States. On the other hand, it was easy for a merchant ship on this run to hug the coast. By doing this, should a hostile cruiser appear anywhere north of Mexico, the merchantman might have a good chance of taking refuge inside the territorial waters of an exceedingly powerful neutral.

Om August 4. 191, the naval force at the disposal of the Admiralty in those waters consisted of three units. This number was soon and unexpectedly increased to five, when, a hours after the war began, the Canadian Government acquired two submarines. Although not immediately ready to act effectively at sea, the submarines offered considerable protection to both coast and trade from Cape Flattery inward, by the deterrent effect of their presence. Two little Royal Navy sloops, The Algerine and the Shearwater, had for some years been stationed on the coast, with their base at Esquimalt. The Algerine was a seasoned veteran, having taken, in the year 1900, a prominent and dangerous part in the action off the Taku Forts in China[12], and the Shearwater was a relic of the once proud Pacific Squadron. Their function was to visit various ports in North and South America, being available to assist British subjects in times of unrest or revolution, and the discharge Great Britain’s responsibility in connection with the sealing patrol. These sloops were useful for police work, but they would have been quite helpless against a cruiser. On the eve of the war they were on the west coast of Mexico, safeguarding British subjects and other foreigners during the civil war between Huerta and Carranza. When Britain declared war on Germany the Algerine and Shearwater sailed for Esquimalt, and during the voyage they were themselves in need of protection, a fact which constituted the Admiralty’s third responsibility. The remaining naval unit in the area, and the only one theoretically capable of taking the offensive, was H.M.C.S. Rainbow.

The German squadron in the Pacific consisted to two powerful armoured cruisers, and of three modern-type light cruisers, the Emden, Nürnberg and Leipzig, besides several small vessels.[13] The squadron, which was commanded by Admiral Graf von Spee, was based in Tsingtau, and had no bases or depots whatever in the eastern Pacific. When the war began the squadron was at Ponape, in the Carolines, and von Spee had a wide choice of objectives. His purposes were, of course, to damage Allied trade, warships, and other interests, on the largest possible scale, and eventually take as many of his ships as he could safely back to Germany. His two most evident anxieties were the possible entry of Japan into the war and the very powerful Australian battle-cruiser Australia. On the morning of August 13 von Spee made the following entry in his diary:-

“ If we were to proceed toward the coast of America, we should have both (coaling ports and agents) at our disposal, and the Japanese fleet could not follow us thither without causing create concern in the United States and so influencing that country in our favour.[14]”

There were no enemy bases there, and the continent was composed of neutral states; consequently von Spee thought that on that coast it would be comparatively easy for him to get coal and communicate with Germany. He evidently meant the coast of South America, and, in the event, it was there that he took his squadron, having first detached the Emden to the Indian Ocean where she began the most distinguished career of any German raider.

The civil war in Mexico had some time before resulted in the formation of an international naval force, under American command, to protect foreigners near the coast. S.M.S. Nürnberg represented the German Navy until she was relieved on July 7, at Mazatlán, by S.M.S. Leipzig, commanded by Captain Haun. On her arrival at Mazatlán found, among other warships, the Japanese armoured cruiser Idzumo and H.M.S. Algerine, and while they were in port together friendly relations were established between the German cruiser and the British sloop. The Shearwater at that time was stationed at Ensenada. At the end of July the American, German, and British warships had co-operated in evacuating the Chinese from Mazatlán and embarking Europeans and Americans, because the Carranzists were about to storm the town. On July 31 the Canadian collier Cetriana arrived at Mazatlán to coal the Leipzig.[15] During the night of August 1 the Leipzig’s guns were cleared for action while she and the Cetriana made ready for sea. In order to keep the collier as ignorant as possible about current events in the field of international relations, the Germans took charge of her wireless set.[16]

On August 1 the Admiralty asked the Canadian Government that the Rainbow might be kept available for the protection of trade on the west coast of North America, where a German cruiser was reported to be.[17] Had it not been for the Government’s earlier decision to send her out on sealing patrol, the Rainbow could not have intervened in connection with the Komagata Maru, nor would she have been fit for sea when war came.

As it was, however, she was ready for sea though not for war, and in accordance with the Admiralty’s request Naval Headquarters in Ottawa telegraphed this order the same day to her captain, Commander Walter Hose, R.C.N.:–

“Secret. Prepare for active service trade protection grain ships going South. German Cruiser NURMBURG or LEIPSIG is on West Coast America. Stop. Obtain all information available as to merchant ships sailing from Canadian or United States Ports. Stop. Telegraph demands for Ordnance Stores required to complete to fullest capacity. Urgent. NAVAL.[18]”

The Rainbow was also ordered to meet at Vancouver am ammunition train from Halifax, which it was hoped would arrive by August 6.[19] The same day the press got wind of a German cruiser’s supposed presence near the coast. “The Rainbow,” said the Victoria Times, “a faster boat and mounting two six-inch guns, is more than a match for the German boat. If Britain engages in war, it will be the business of the Rainbow to get this German boat,”[20]

After receiving her orders the Rainbow was alongside at the Dockyard or anchored in Royal Roads, preparing for war, and on August 2 she reported herself ready for sea.[21] The railway and express companies were not organized for war, and their refusal to handle explosives was a tangle that had to be unraveled before the promised ammunition train could start. In any case it could not arrive for several days, while the European crisis was becoming more acute every hour. The cruiser therefore had to meet her needs as best she could from old Imperial stores in the Dockyard.[22] When all possible preparations had been made, the Rainbow remained weak at many points. Her wireless set had a maximum night range of only 200 miles, though this defect her wireless operators were able to overcome at a later date. An almost incredible fact is that she had no high-explosive ammunition; all she had been able to obtain was old-fashioned shell filled with gunpowder.[23] She had no collier and no dependable coaling-station south of Esquimalt. Less than half the full complement was on board, and more than a third of these were Royal Naval Canadian Volunteer Reservists, many of whom knew nothing of eh sea or of warships. There was little likelihood, however, that the enemy would learn of the Rainbow’s deficiencies in shells and men, and the German official history – which refers to her as “the Canadian training-ship Rainbow” – gives no indication that they did so.

In the afternoon of August 2 Commander Hose received the following message directly from the Admiralty:-

“LEIPZIG reported left Mazatlan, Mexico 10 a.m. 30th July. Rainbow should proceed south at once in order to ger in touch with her and generally guard trade routes north of the equator.[24]”

As Hose did not know whether or not the Canadian Navy had come under the Admiralty’s orders, he repeated the above message to Ottawa with a request for instructions, and ordered the fires lit under four boilers. Shortly afterwards he wired to Ottawa:-

“With reference to Admiralty telegram submitted Rainbow may remain in the vicinity Cape Flattery until more accurate information is received LEIPZIG, observing that in event of LEIPZIG appearing Cape Flattery with RAINBOW twelve hundred miles distant and receiving no communications, Pacific cable, Pachena W(ireless), T(elegraph), Station, and ships entering straits at mercy of LEIPZIG with opportunity to coal from prizes. Vessels working up the West Coast of America could easily be warned to adhere closely to territorial waters as far as possible. Enquiry being made LEIPZIG through our Consul.”[25]

Headquarters did not approve his suggestion, and at midnight, August 2-3, this signal arrived from Ottawa:-

“You are to proceed to sea forthwith to guard trade routes north of Equator, keeping in touch with Pachena until war has been declared obtain information from North Bound Steamers. Have arranged 500 tons coal at San Diego. United States does not prohibit foreigners from coaling in her ports. Will arrange for credits at San Diego and San Francisco. No further news of Leipzig.[26]”

The Admiralty knew that the Leipzig was, or had very recently ben in Mexican waters, and thought it possible the Nürnberg might also be cruising somewhere near that coast. Lloyd’s thought that both the German cruisers were operating on the west coast of North America and warned shipping accordingly.[27] It goes without saying that rumours grew thick and fast along the coast, flourishing in the fertile soil of uncertainty. For the most part these rumours either consisted of, or had as their least common denominator, the reported presence and doing of the Leipzig and Nürnberg. Thought the Leipzig was actually near the North American coast, the Nürnberg was not; yet the story of her presence with the Leipzig is still repeated as fact, as the rumour which was current in those days that one or both of these cruisers operated in the coastal waters of British Columbia.

A reasonably precise statistical picture of the Rainbow is afforded by the following figures:-

Launched | 1891 |

Displacement | 3,600 tons |

Length | 300 feet |

Beam | 43 ½ feet |

Draught | 17 ½ feet |

Horse-Power (Designed | 9,000 |

Designed Speed | 19.75 knots |

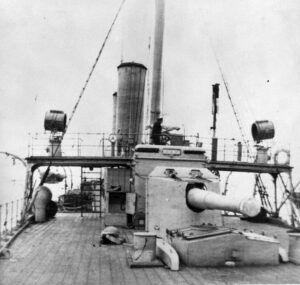

Armament | 2 6-inch, 6 4.7-inch 4 12-pounder guns 2 14-inch torpedo tubes |

Full complement | About 300 |

Twenty-three years old, she was obsolescent, and much inferior to either the Leipzig or the Nurnburg in speed or type of armament, though she was slightly larger than either of them. On account of her age her maximum speed was only about 17 knots. Some features of the other warships which appear prominently in the story are given in the table below.

Displacement (Tons) | Main Armament | Designed Speed (Knots) | Laid Down | |

Leizpig | 3250 | 10 4.1 inch | 23 | 1904 |

Nurnburg | 3450 | 10 4.1 inch | 23.5 | 1905 |

Newcastle | 4800 | 2 6 inch, 10 4 inch | 25 | 1909 |

Idzumo | 9800 | 4 8 inch 14 6 inch | 20.75 | 1898 |

Algerine | 1050 | 4 4 inch | 13 | 1894 |

Shearwater | 980 | 4 4 inch | 13 ½ | 1899 |

At 1 a.m., on August 3, the Rainbow put to sea from Esquimalt, and, according to a well-informed witness, “but few of those who saw her depart on that eventful occasion expected to see her return.”[28] Yet if any protection at all were to be given to the two helpless sloops and to shipping off the coast, the Rainbow had to be sent out since nothing else was available. She rounded Cape Flattery and steamed southward, proceeding slowly so as to keep in touch with the Pachena wireless station. With the same end in view, at 4 a.m. on August 4 she altered course to the northward, having reached a point a little to the southward of Destruction Island, 45 nautical miles down the coast from Cape Flattery.[29]

The same day the Rainbow was informed that war had been declared against the German Empire,[30] and at this time she became the first ship of the Royal Canadian Navy ever to be at sea as a belligerent. On this day too, an Order in Council placed the cruiser at the disposal of the Admiralty for operational purposes.[31] Since the early hours of August 3, all hands had been engaged in preparing the ship for action, exercising action stations, and carrying out firing practice in order to calibrate the guns. At 5:30 p.m. on August 4 a southward course was set, the objective being San Diego; but three hours later a signal was received to the effect that the inestimable high-explosive shell had reached Vancouver, and the course was altered accordingly.[32] Off Race Rocks at 6 a.m. on August 5 the following message from Naval Headquarters reached the Rainbow:-

“Receive from Admiralty. Begins —“Nurnburg” and “LEIPZIG” reported August 4th off Magdalena Bay steering North. Ends. Do your utmost to protect Algerine and Shearwater steering north from San Diego. Remember Nelson and the British Navy. All Canada is watching.”[33]

The cruiser therefore turned about once more and proceeded down the coast at 16 knots, with no high-explosive shell. Since the two submarines which had been bought in Seattle arrived at Esquimalt that morning, the waters which the Rainbow was leaving would thenceforth enjoy the protection which their presence afforded. At 6 a.m. on August 6 the cruiser was abreast Cape Blanco, and she arrived off San Francisco twenty-four hours later.

A curse which lies heavily upon those responsible for the operations of war ships since the age of sails is the relentless need of fuel. Let the bunkers or tanks be emptied and propellers cease to turn, while a reduced store of fuel means a shorter radius of action. Commander Hose therefore decided to put in for the purpose of filling up with coal. He also wished to obtain the latest information from the British Consul-General. At 9:30 a.m. on August 7 the Rainbow anchored in San Francisco harbour. Only an hour and twenty minutes later the German freighter Alexandria of the Hamburg-Amerika Line was sighted off the Heads, inward-bound. She had been requisitioned by the Leipzig a few days before and ordered to discharge her cargo at San Francisco. After taking in coal and some lubricating oil, she was to go to a rendezvous with the Leipzig.[34] A richly-laden enemy ship which was about to become an auxiliary to a hostile cruiser would have been no ordinary prize.

The Rainbow did not experience much better luck in San Francisco than she had met with outside.

“On arrival in Port was boarded by Consul-General who informed us that 500 tons coal were in readiness. Made arrangements to go alongside when informed by Naval & Customs authorities that in accordance with the President’s Neutrality proclamation we could only take in sufficient coal to enable us to reach the nearest British Port. As we already had sufficient, it meant we could not coal; at all, but on the plea we had not a safe margin, we were permitted to take 50 tons. The Consul-General could give no news of the “Algerine” and “Shearwater” and stated that last news of “Leipzig” was that she coaled at La Pas two days previously. All through that day various conflicting reports were received regarding the two German cruisers.[35]

The Consul-General’s information before the Rainbow left was that both German cruisers had been seen near San Diego steering north.[36] Four former naval ratings joined he ship here, and at 1:15 a.m. on August 8 she weighed and will all lights extinguished sailed out of the bay.

Instructions had been sent to Commander Hose from Ottawa early on the same day.

“Your actions unfettered considered expedient however you should proceed at your utmost speed north immediately, order will be given Algerine, Shearwater wait Flattery.”

The cruiser had sailed, however, before this signal arrived. She steered northward so as to keep between the enemy who was thought to be very near San Francisco, and the little sloops, and also because a store-ship was expected from Esquimalt, which was to meet the Rainbow near the Farallones Islands. The morning watch was spent in tearing out inflammable woodwork and throwing it overboard. Flotsam from a warship. Doubtless the Rainbow’s woodwork, which was reported to have been found shortly afterwards near the Golden Gate, caused some anxiety.[37] During the 8th and 9th the Rainbow cruised at low speed in the neighbourhood of the Farallones, whose wireless station kept reporting her position en clair. By the morning of August 10, the Rainbow’s supply of coal was running low. No German cruiser, nor British sloop, nor store-ship had been sighted. It seemed probable that the sloops must have got well to the northward by this time, and at 10 a.m. the cruiser altered course for Esquimalt.[38]

The Rainbow was operating alone on a very dangerous mission. In order to reduce to some extent the risks which were being run by her complement, the S.S. Prince George was hurriedly fitted up as a hospital ship and sent out from Esquimalt to meet the Rainbow and accompany her. The Prince George, a fast coastal steamer owned by the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway, had three funnels,[39] a cruiser stern, and a general appearance not unlike that of a warship. On the 12th, about 8 o’clock in the morning, a vessel which appeared to be a warship was sighted by the Rainbow’s lookouts. The cruiser immediately altered course about fourteen point, and put on full speed while all hands went to action stations. A few minutes later the stranger was identified as a merchant ship which turned out to be the Prince George. The latter carried an order that Hose should return to Esquimalt, and both vessels accordingly proceeded towards Cape flattery. Early next morning about 20 miles from Esquimalt they found the Shearwater at last; she had no wireless set, and her first question was whether or not war had been declared. Shortly after 6 a.m. Esquimalt was reached.

The Shearwater’s commander was unable to supply any news of the Algerine, and expressed great anxiety regarding her. Headquarters reported that she had been of Cape Mendocino on August 11th, and Hose now obtained permission to go down the coast as far as Cape Blanco in order to find and protect her.[40] The Rainbow was coaled as quickly as possible and a consignment of high-explosive shell taken on board; but the delight of the gunners was short-lived since there were no fuses. Twenty of the volunteers on board who had experiences as much of the seafaring life as they could endure were replaced from shore. At 5:30 that evening the cruiser set out once more, at full speed, to look for the Algerine, which was sighted at 3 o’clock the next afternoon. The little vessel had been struggling northward against headwinds. Having run short of fuel she had stopped a passing collier and was engaged in getting coal across in her cutters. As the Rainbow approached, the Algerine signalled: “I am dammed glad to see you.”[41] When the sloop was ready to proceed the Rainbow took station astern and late in the afternoon of August 15 they reached Esquimalt. The most pressing naval responsibility in these waters had now been discharged. Before the Rainbow went to sea again she had received fuses for her high-explosive shells.

On August 11, 12 and 13 the Leipzig and Nurnburg were reported to be off San Francisco.[42] It was also rumoured that they were capturing ships in the approaches to the Golden Gate, and the stories which travelled up and down the coast paralyzed the movements of British shipping from Vancouver to Panama.[43] On August 14 the two cruisers were reported to be headed for the north at full speed. “Should they continue directly up the coast,” wrote the editor of the Victoria Times, “they will get all the fighting they want. The Rainbow and the two smaller vessels will be ready for them.[44] Shortly after midnight, on the morning of the 17th, the Leipzig herself sailed boldly into San Francisco harbour in order to coal, and her commanding officer, Captain Haun, received a group of newspaper-men on board. His fighting spirit flamed as brightly as did that of the Times editor. “We shall engage the enemy,” he told the San Francisco reporters, “whenever and wherever we meet him. The number or size of our antagonists will make no difference to us. The traditions of the German navy shall be upheld.” The Leipzig’s captain landed, called on the mayor, presented the local zoo with a couple of Japanese bear cubs, and put to sea at midnight.[45] Meanwhile the Rainbow at Esquimalt had been preparing to go to sea once more. While Japan had not yet declared war on Germany, the powerful Japanese cruiser Idzumo, which had represented her country in the international naval force in Mexican waters, was still on the west coast and it was reported that her commander intended to shadow the Leipzig. The Victoria Times offered words of sympathy” “Unhappy cruiser Leipzig! For the next six days she is going to be stalked wherever she may go by a warship big enough to swallow her with one bite.”[46]

From August 4 to August 23, when Japan entered the war, the warships at the Admiralty’s disposal on the Pacific Coast of North America were incapable of destroying, bottling up, or driving away, both or either of the German cruisers, a fact which was emphasized by the widely advertised entry of the Leipzig into San Francisco. The waters in question clearly required more protection. The Admiralty accordingly ordered the Admiral commanding on the China Station to send one of his light cruisers, and on August 18 H.M.S. Newcastle left Yokohama for Esquimalt,[47] The Newcastle was a light cruiser of the Bristol class[48] – she was a newer ship than either of the Germans and was faster and more powerfully armed. The same day Commander Hose asked for permission to take the Rainbow to San Francisco in order to find and engage the Leipzig. The Admiralty approved the suggestion and the following order was sent to the Rainbow at sea:-

“Proceed and engage or drive off LEIPZIG from trade route; do not follow after her ….. You should cruise principally off San Francisco.”[49]

These instructions, of course, were based on the idea that the Leipzig might be molesting shipping in the approaches to San Francisco. The same day, however, the order was countermanded, because both the German cruisers were reported off San Francisco, and the Rainbow returned to Esquimalt to await the arrival of the Newcastle.

The most exposed town on the British Columbia coast was Prince Rupert, which had no local protection whatever. The war had consequently brought a feeling of uneasiness to many of the citizens, and the mayor arrived in Victoria a few days after hostilities began, hoping to obtain some defences for the town.[50] Rumours that one or both of the Germans were on their way northward had been current for some time, and on August 19 a cruiser with three funnels – the Leipzig and Nurnburg each had three funnels – was reported to be in the vicinity of Prince Rupert.[51] Before dawn next day the Rainbow set out for the northern port, which she reached on August 21, and where inquiries elicited further evidence that a strange cruiser had been seen. Two days after his arrival Commander Hose telegraphed to Ottawa:-

“Strong suspicions Nürnberg or Leipzig has coaled from U.S. Steams hip Delhi in vicinity of Prince of Wales Island on Aug. 19th or Aug 20th.”[52]

The carrying of coal to Prince Rupert by water in British ships was immediately stopped. The suspicions were never confirmed, and whatever the cause of anxiety may have been, it was not a German cruiser.

A similar rumour had germinated during the Spanish-American War. In July, 1898, the Admiralty sent the following message to the Commander-in-Chief at Esquimalt:-

“The American Consul, Vancouver, has reported that a Spanish privateer of five guns is in the waters near Queen Charlotte Sound, apparent(ly) on look out for vessels going to and from Klondyke and is suspected of endeavouring to obtain a British pilot.”

Warships of the Pacific Squadron at Esquimalt went north to look for the Spaniard but found nothing. In this case the anxiety was lest a belligerent warship might compromise British neutrality.[53]

The Rainbow remained in the north until August 30 when she left for Esquimalt. When Japan had declared war on August 23, the Japanese armored cruiser Idzumo had been at San Francisco. Two days later, firing a salute as she came in, the Idzumo dropped anchor in Esquimalt. The Newcastle reached Esquimalt on the 30th, and the Canadian warships, together with the Idzumo, came under the orders of her commander, Captain F.A. Powlett. On September 2, the Rainbow arrived at Esquimalt. During the month of August, she had steamed more that 4,300 miles.

On September 3 the Newcastle left Esquimalt to look for the Leipzig.[54] Captain Powlett’s first idea had been to take the Rainbow with him; but after that ship’s return from the north she needed a few days in dockyard hands, and was therefore left behind to guard the ends of the routes leading to the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The Idzumo was detailed to watch the approaches to San Francisco. The Nurnburg had been seen at Honolulu on September 1, a fact which rendered it unlikely that she would appear off North America. There were numerous stories which pointed untrustworthy fingers at the whereabouts of the Leipzig, and some of these, as so often happens in time of war, seemed to rest on first-hand evidence, as when a tanker arrived in Seattle on August 21 and reported she had been stopped by the Leipzig 150 miles north of San Francisco.[55] Since August 18, however, no certain news of her whereabouts had been received, and the disturbance to trade which she had caused was rapidly subsiding. The Newcastle carried out a thorough search along the coast down to and including the Gulf of California, and, on her way, she established a series of improved lookout and intelligence stations on shore which assured her of receiving immediate information should the Leipzig return to her former hunting-grounds. Captain Powlett then concluded that the Leipzig had gone too far south to be followed, and he therefore returned to Esquimalt. There was a bare possibility that if other parts of the Pacific got to hot for them, the German Pacific Squadron might come to the North American Coast, where, in addition to causing havoc among shipping, they might even attack Vancouver or the coal mines at Nanaimo. With this in mind Captain Powlett suggested measures of shore defence at these points and made arrangements for mines to be laid in suitable areas should the need arise.

On September 30, the Newcastle set out on a second reconnaissance of the coast as far south as the Gulf of California leaving the Idzumo and the Rainbow behind on guard as on the previous occasion. While the Newcastle was on her two cruises, the Rainbow had watched her part of the trade routes, keeping a lookout for supply ships from United states ports, and engaging from time to time in gun and torpedo practice.

The actual operations of the German cruisers, details of which are now known to us, remain to be described.[56] The Nurnburg left Mazatlan on July 7, called at Honolulu, and joined von Spee on August 6 at Ponape. She later revisited Honolulu and rejoined her squadron on September 6. The same day she was detached to destroy the Canada- Australia cable and cable-station at Fanning Island. On September 7 she landed a party there which cut the cable and destroyed the essential installations on shore. She then returned to von Spee once more. It is almost certain that after the outbreak of war the Nürnberg was never less than about 2,500 miles from the coast of British Columbia. She strongly influenced the movements of the Rainbow and other allied warships, but she did so in absentia.

The Leipzig was at Magdalena Bay, when on August 5, she received the news that Great Britain had declared war. Her mobilization orders instructed her to join von Spee in the western Pacific; but before he did this Captain Haun wanted to make sure oof his coal-supply. The problem of fuel almost stultified all the German surface raiders, and it seemed to have been unusually difficult on the west coast of America.

“German warships very seldom visited the north-west coast of America, and it had always been thought that these waters would not be of much importance to Germany in time of war. Accordingly, the Naval Staff had made little preparation for furnishing coal and provision s to warships in this area.”[57]

Of such organization as there was, San Francisco was the principal centre. Captain Haun therefore telegraphed to that port, asking that arrangements be made to send coal and lubricating oil to him at sea. Early on August 5 the Leipzig left Magdalena Bay for San Francisco, following a circuitous route. On the night of August 6 she heard the press radio service at San Diego reporting that the British naval force on the west coast consisted of the Rainbow, Algerine, Shearwater, and two submarines bought from Chile. Captain Haun hoped that after coaling he would be able to do some local commerce-raiding before joining von Spee, and for that purpose the most likely hunting-grounds in those waters were considered to be the areas of Vancouver, Seattle and Tacoma, San Francisco, and Panama.

“Captain Haun naturally weighed the advisability of winning an immediate military success by attacking the Algerine and Shearwater on their way to Esquimalt, by capturing on of the Canadian Pacific liners which could be fitted as an auxiliary cruiser, or by attacking the Canadian training-ship Rainbow. Considering the importance of commerce-raiding, however, these enterprises would scarcely have been justified; for even a successful action with the Rainbow, which was an older ship, but which had mounted a heavier armament, might have resulted in such serious damage to the Leipzig as would have brought her career to a premature end.[58]

On August 11, in misty weather and apparently in the forenoon, the Leipzig reached the approaches to the Golden Gate, near the Farallones islands, the German consul came on board. He told Captain Haun that Japan would probably enter the war and that the presence of the Rainbow north of San Francisco had been reported. The consul said that American officials were unfriendly in the matter of facilities for coaling and also said that he had not been able so far to obtain either money or credit with which to pay for coal.

“When the German consul met the Leipzig, he was not even sure that the United States authorities would permit her to coal once, in spite of the fact that no objection had been made to supplying the Rainbow. Such a refusal would have made it necessary to lay up the Leipzig before she had struck a single blow. As Captain Haun and his crew could not bear to think of such a thing, he determined to remain at sea for as long as he could, to try to hold up colliers and other merchant ships off the Golden Gate, and then to steam Northward and engage the Rainbow. He therefore told the consul he would return to San Francisco on the night of August 16-17 and enter the harbour, unless he should have been advised not to do so.

The Leipzig cruised in territorial waters on August 12, proceeding as far as Cape Mendocino. She then made for the Farallones Islands, keeping from twenty to thirty miles from the coast. The Rainbow was not sighted, and all the merchant-ships that came along were American. These the Leipzig did not interfere with in any way, so as not to wound American susceptibilities.”[59]

At the appointed time the Leipzig returned to San Francisco. She entered the harbour just after midnight, paying a visit which has already been described, and twenty-four hours later she left after taking aboard 500 tons of coal.

“When she had cleared the harbour the Leipzig steamed at high speed towards the Farallones Islands, without lights and ready for action. After August 18 she proceeded outside the trade routes at seven knots, steaming on only four boilers while the others were cleaned. On August 26 she passed Guadalupe. Because future supplies of coal were so uncertain, it was impossible for her to raid commerce, especially as British ships were being kept in port, while the searching of neutral vessels would merely have advertised the Leipzig’s whereabouts.”[60]

The cruiser continued her way down the coast, she left the Gulf of California on September 9, well supplied with coal, and proceeded on her southward journey, making her first captures as she went.[61]

During the opening weeks of the war, Admiral von Spee’s squadron had been cruising the Pacific in a leisurely fashion, far to the southward.[62] In the words of Admiral Tirpitz:-

“The entry of Japan into the war wrecked the plan of a war by our cruiser squadron against enemy trade and against the British war ships in these seas, leaving our ships with nothing to do but to attempt to break through and reach home.”[63]

Von Spee was able to remain undetected because of the vast size of the Pacific, and because the strength of his squadron forced his enemies to concentrate. The Leipzig joined him on October 14 at Easter Island. His squadron arrived at last off the coast of South America, where, on November 1, it engaged and almost completely destroyed a British squadron off Coronel[64] – a battle in which the Leipzig took part and in which the Nurnburg sank the already seriously damaged H.M.S Monmouth. The arrival of von Spee off the South American coast had not for long remained a secret, and the Admiralty tried to bar his path wherever he may go. It was possible that he might elect o sail northward, in order to go through the recently opened Panama Canal or to the west coast of North America. To deal with such a move on his part a British-Japanese squadron was formed off the Mexican coast, whence it proceeded to the Galapagos Islands. This concentration proved to have been unnecessary, however, for after Coronel, von Spee moved southward. After rounding South America, he ran headlong into a decisively stronger British force on December 8 at the Falkland Islands, where all his ships save one were sunk. The Nürnberg met her end at the hands of H.M.S. Kent, after an epic chase during which the Kent’s stokers, in order to squeeze out a little more speed, burned up nearly all the woodwork in the ship. The Leipzig was sunk by the Cornwall and the Glasgow, only eighteen of her officers and men being saved. The very fast Dresden alone escaped, to remain at large in South American waters until, on March 14, 1915, she too was found and destroyed.

It seems evident that at the outbreak of the war, Captain Haun’s intention had been to obtain coal in order to join von Spee, seizing or sinking and British merchant ship which he might meet en route, He probably wanted to take a collier with him when he should start to cross the Pacific and, apart from this consideration, the need to fill his own bunkers prolonged his stay on the coast. The only ports available to him were neutral ones in which he could not stay for more than twenty-four hours, and to enter which would tend to defeat his purpose as a raider. When he did, in fact, enter San Francisco, the news spread far and wide, and British merchant ships in the neighbourhood went into hiding or postponed their sailings. Moreover, his presence in port might have brought up the Rainbow, to force an action under circumstances which could have been very unfavourable for him. To remain at sea, on the other hand, meant burning his precious coal. Operations by the Leipzig anywhere on that coast were severely hampered by her orders to join von Spee, and by the fact that the nearest German base was thousands of miles away.

Did Captain Haun desire to engage the Rainbow? On the information available, it is highly probable that he considered his principal obligations to be, in the order of priority, to join von Spee, to damage commerce, and to engage enemy warships. Of these duties, the last two as well as the first, in order of precedence, may have ben assigned to him by von Spee. If not, they were prescribed for his case by any orthodox treatises on naval doctrine with which he may have been familiar. Captain Haun did not know about Rainbow’s obsolete shells; but he did know that serious injury to the Leipzig, situated as she was, would probably have deprived his country of a fine cruiser for the duration of he war. It is suggested that Captain Haun would have been very pleased to see the Rainbow, and that had he done so he would have attacked at once; but that only during August 13 and 14 did he feel free to search for her.

During her operations between August 4 and September 10, the Leipzig failed to lay hands upon a single merchant vessel or warship, or to alarm by her visible presence any Canadian community. Turning to the other side of the ledger, some anxiety was caused among the coastal population of British Columbia – banks in Vancouver and Victoria, for example, transferred some of their cash and securities to inland or neutral cities.[65] A serious effect upon British shipping was also produced:-

“….In view of the frequent reports received as to the supposed movements of these ships (Leipzig and Nurnburg), owners were generally unwilling to risk their vessels until the situation should be cleared up. Chartering was suspended at all ports on the coast, and most tramp steamers remained in port, while the liners services were curtailed and irregular ….. (but) within two or three weeks of the Leipzig’s departure from San Francisco trade had become brisk all along the coast.”[66]

Most important of all, the attention of three Allied cruisers, of which two were considerably more powerful than the Leipzig herself, was wholly occupied until the German cruiser was known to have removed herself from the area. It is quite safe to say that during the first six weeks of the war, from the point of view of the German government, the Leipzig was a paying concern. The dividend would probably have been smaller, however, had it been known she was operating alone.

After Coronel the Rainbow co-operated for a time with the British-Japanese squadron which had been formed in order to meet von Spee should he turn northward, and to which reference has already been made. She could not keep up with the other ships, and was frequently used as a wireless link between them and Esquimalt. At a time when it was thought likely that von Spee would turn northward, Commander Hose sent the following signal to the Director of the Naval Service:-

“Submit that Admiralty may be asked to arrange with Senior Officer of Allied Squadron —– that Canadian ship Rainbow shall if possible be in company with squadron when engaged with enemy.”[67]

He received in reply a refusal, with reasons for the same, one of them being that “If the Rainbow were lost, immediately there would be much criticism on account of her age in being sent to engage modern vessels”[68] Among the squadron whose lot her commander wished to share was the battle-cruiser Australia.

After the German squadron had entered the Atlantic the threat to the Pacific coast of North America was greatly diminished, and with the destruction of the Dresden it ceased altogether as far as German cruisers were concerned, the only danger thereafter, which was present until the entry of the United States into the war in 1917, lay in the possibility of German agents might send out merchantmen lying in neutral harbours, armed as commerce raiders. This threat, though it never actually materialized on that coast, was a real one none the less. German sympathizers were at work at various neutral ports and attempts were probably made to send out raiders. The Rainbow was well adapted to the work of intercepting armed merchant ships. She was less vulnerable than a liner, faster than any except the swiftest of them, and very adequately armed. The nature of this problem and some of the means used to deal with it, are clearly illustrated in the case of the S.S. Sazonia.

On August 1, 1914, the Hamburg-Amerika liner Sazonia was at Tacoma taking aboard 1,000 tons of hay for Manila. On orders from her company she unloaded the hay and went to Seattle where she tied up. Late in October the naval authorities at Esquimalt learned that the Sazonia would probably be transferred to American registry, and that she had been measured for the Panama Canal, which had been opened for traffic during the summer. The British Vice-Consul at Tacoma made inquiries and arranged to have the ship kept under observation. She did not leave, and in March 1915, Esquimalt was warned by the postmaster at Victoria that she would probably try to do so on the night of March 16, and that guns were awaiting her at Haiti and gun-mountings at New York. Ottawa was notified, and spread a wide net by passing the warning on to the Admiralty, St. John’s Newfoundland, the Embassy in Washington, and the Vice-Consul at Tacoma. Naval measures were also taken to block the exit of the Sazonia through the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The Vice-Consul went to Seattle on March 16, and after dark he patrolled the entrance to the port in a motor-launch until 1 a.m. He then entered the harbour and circumspectly investigated the Sazonia at close quarters, she had no steam up, and the Vice-Consul decided she would not sail that night, and that she would never be able to raise steam without being observed by his agents in a nearby shipyard. It was reported on several subsequent occasions that she was about to sail. In the end the Untied states authorities seized the Sazonia; but not before her faithful crew had out her engines out of commission by damaging the cylinder heads and by throwing overboard various indispensable parts.[69]

Another part of the Rainbow’s task during the rest of her commission was to assist in preventing German shipping, open or disguised, from using coastal waters. By the end of October she had two hundred and fifty-one officers and men on board. Of this total, eight officers and fifty-one ratings belonged to the Royal Navy, and five officers and forty-five ratings to the Royal Canadian Navy, while two officers and fifty-two men were Naval Volunteers.[70] On December 18 the Rainbow left Esquimalt to superintend the dismantling of certain guns which had been temporarily placed at Seymour Narrows to prevent an enemy from entering the Strait of Georgia by the northern route. The following spring, she did useful reconnaissance work off Mexico. In February 1916, she set out once more for a similar patrol of Mexican and Central American waters, her freedom of movement being greatly enlarged by the presence of a collier, during this cruise the Oregon, a vessel on the American register, was intercepted on April 18 near La Paz. A boarding-party was sent over to her, and after a search it was decided to send her to Esquimalt with a prize crew aboard. On May 2 the Mexican-registered Leonor owned by a German firm, was also seized. This schooner had taken part in coaling the Leipzig in the Gulf of California. These prizes were both taken on the ground that they were actually German ships whose neutral registry was a disguise for activities which were in the interest of the enemy. They had to be towed a good part of the way home, and as a result of the delay provisions ran short. The Rainbow therefore pushed on ahead of her collier and on May 21 shew reached Esquimalt. From August 8 to December 14, 1916, the Rainbow was on a third cruise of the same kind, during which she went as far south as Panama.[71]

Early in 1917 the submarine war was entering its most critical phase and both the Canadian Government and the Admiralty were working against great difficulties to create an adequate fleet of anti-submarine vessels off the east coast of Canada. The most serious problem was to find enough trained men, and the Canadian Government suggested that as the Rainbow was rapidly approaching the time, she would have to be extensively refitted, it might be better to pay her off and transfer her crew to the patrols. The Admiralty concurred.[72] The Japanese Admiralty had long since assumed responsibility for the whole of the North Pacific except for the Canadian coastal waters, and the small remaining possibilities of danger were cleared away on April 6, 1917, when the United States entered the war. The Rainbow performed her last war service in the training of gunners for the patrol-vessels and was paid off on May 8. She reverted to the disposal of the Canadian service on June 30, 1917 and was recommissioned as a depot ship at Esquimalt. She was placed out of commission in 1920, and sold for $69,777 to a firm in Seattle to be broken up.

What would have happened, during those opening weeks of the war, had the Rainbow met the Leipzig? Captain Haun would almost certainly have attacked. The Rainbow was older and slower than the German cruiser, and less effectively manned. The type of main armament which she mounted, consisting of guns of two calibres, was less efficient than that of the Leipzig., because a mixed armament makes spotting more difficult. The Rainbow’s 6-inch guns were probably inferior in range to the Leipzig’s much smaller weapons.[73] German gunnery, too, at this time, was the best in the world. Even with these great disadvantages, however, the Rainbow would probably have had a very uneven chance of disabling or even destroying her opponent, had all else been equal which it was not. The fact that during the critical period she had only gunpowder -filled shells on board made the Rainbow nearly helpless, and had she encountered the Leipzig she would almost certainly been sunk, unless she could have taken refuge quickly inside the 3-mile limit. Her only other chance would have lain in a good opportunity to use her torpedoes – a windfall of fortune almost o improbable to be considered.

The Rainbow performed useful serviced during the war. She afforded a considerable measure of protection to the coast of British Columbia and the moral effect of her presence there was very valuable, especially during the first three weeks. After the arrival of the Idzumo and Newcastle. She played a useful if secondary part. The Rainbow was unable to provide much protection to trade; the Leipzig searched for merchant ships as freely as her coal-supply and orders permitted, and temporarily succeeded in clearing the nearby waters of British ships.

”At the same time, the presence of the Rainbow was even more effective in putting a stop to German trade. The few enemy steamers on the coast cut short their voyage at the nearest port, sending their cargoes under an American flag, and numerous sailing vessels of large size were held up in Californian and Mexican harbours.[74]

The Rainbow’s services throughout were more restricted and much less valuable than would have been the case had she been newer and consequently faster and more powerful. If she had succeeded in disabling the Leipzig, it is obvious that von Spee’s squadron would have been seriously weakened, the young Canadian naval service would have benefited immeasurably, and in a host of ways, had the Rainbow been able to cloth herself in a mantle of glory as Australia’s Sidney did; but this, humanly speaking, she could not hope to achieve. She had been acquired purely as a training ship and not in order to fight. Obsolescent vessels are very useful in times of war, but only for duties which take account of their limitations. Because of Rainbow’s outmoded design and defective ammunition, moreover, her officers and men had to be sent out expecting to face almost hopeless odds. They had to be placed in a very unfair moral position as well. Uniformed opinion on shore concerning the Rainbow as a ship alternated illogically between ridicule and a tendency to regard her merely as a cruiser and therefore a match for any other cruiser. Her compliment did all that could have been done with the instrument at her disposal, and cheerfully faced danger with little prospect of earning the fame which crowns unqualified success. They served their country well.

Gilbert Norman Tucker

Department of the Naval Service

Ottawa,

[1] Naval Service Records, Ottawa (hereafter cited as “N.S.R.”), Folder No. 2-5-2. The account of the Rainbow’s cruise to Esquimalt is based, except where otherwise indicated, on material contained in this folder and in the cruiser’s Log.

[2] See confidential report by the British Naval attaché in Berlin, in Gooch and Temperley, British Documents on the Origins of the War, 1898 – 1914, VI., London, 1930, pp 506-510.

[3] Victoria Daily Times, Victoria, B.C., November 7, 1910.

[4] Victoria Daily Colonist, Victoria, B.C., November 8, 1910.

[5] Times, Victoria, November 7, 1910.

[6] Colonist Victoria, November 8, 1910.

[7] Letter of proceedings, December 2, 1910. N.S.R., 2-5-1.

[8] Based on estimates contained in a digest by the Assistant Naval Secretary. N.S.R. 1001-5-1

[9] For a full account se Robie L. Reid, “The Inside Story of the Komagata Maru”, British Columbia Historical Quarterly, V, 1941. pp 1-23

[10] Hose to Hdq., July 20, 1914, N.S.R. 1048-3-9(2)

[11] Henry Borden (ed.) Robert Laird Borden, His Memoirs, Toronto, 1938. I, p 449.

[12] See Sir Roger Keyes, Adventures Ashore and Afloat, London, 1939, pp210-227; Major F.V. Longstaff, Esquimalt Naval Base, Victoria, BC, 1941, pp 164-166.

[13] This paragraph is based almost entirely on the German Official Naval History, Der Keieg sur See, 1914-1918: Der Kreuzkrieg in den auslandischen Gewãesern (by Vice Admiral E. Raeder), I., Berlin, 1922.

[14] Kreuzkrieg, I, p 80, (translation).

[15] The Cetriana was owned in Vancouver, her master was a Royal Navy Reservist, and she was chartered in the spring by the Nurnberg’s commander, to carry coal and other supplies to him from San Francisco. After the Germans had chartered her, according to the British consul in San Francisco, the Cetriana had engaged a fresh crew consisting mainly of Germans and Mexicans. (Consul-General, San Francisco, to Naval Service Hdq. Ottawa, September 12, 1914. N.S.R. 1048-10-2.)

[16] This paragraph is based on the account in Kreuzkrieg, I, chapter V.

[17] Secretary of State for the Colonies to Governor-General’s Secretary, n.d., Copy in N.S.R. 1047-19-3 (1).

[18] Hdq. To Hose, August 1, 1914. Copy ibid.

[19] Hdq. To Commander-in Charge, Esquimalt Dockyard, August 1, 1914. Copy ibid.

[20] Times, Victoria, August 1, 1914.

[21] Dockyard to Hdq. August 2, 1914. N.S.R. 1047-19-3 (1).

[22] Hdq. To Admiralty, August 3, 1914. Copy in N.S.R. 1046-1-48(1).

[23] Copy of diary in the possession of Commander E. Haines, M.B.E., R.C.N. Commander Haines was the Rainbow’s gunnery officer.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Hose to Hdq. August 2, 1914. N.S.R. 1047-19-3 (1).

[26] Hdq, to Hose, August 3, 1914. Copy ibid.

[27] Times, Victoria, August 5, 1914.

[28] George Phillips, “Canada’s Naval Part in the War.” The author was superintendent of the Esquimalt Dockyard. MS lent by Mrs. Phillips.

[29] The Rainbow’s movements throughout are based on her Log.

[30] Hose to Hdq., August 4, 1914, N.S.R. 1047-19-3(1).

[31] P.C. 2049, August 4, 1914.

[32] Diary in possession of Commander Haines.

[33] Hdq. To Hose, August 5, 1914. Copy in N.S.R. 1047-19-3(1)

[34] Kreuzkrieg I, Chapter V.

[35] Extract of Letter of Proceedings, August 2 -17, 1914, in possession of Commander Haines.

[36] Hose to Hdq., August 7, 1914. N.S.R. 1047—19-3(1)

[37] Hdq. To Admiralty, August 11, 1914. Copy Ibid. Times Victoria, August 13, 1914.

[38] Extract of Letter of Proceedings, August 2 – 17, in procession of Commander Haines

[39] The Leipzig and Nurnburg each had three funnels.

[40] Signals in N.S.R. 1047-19-3 (1)

[41] Diary in possession of Commander Haines

[42] The Leipzig was, in fact, close to San Francisco on the 11th and 12th. Se infra

[43] (British Official History) C. Ernest Fayle, Seaborne Trade, I., London and New York, 1920, p 163.

[44] Times, Victoria, August 14, 1914.

[45] Colonist, Victoria, August 18, 1914.

[46] Time, Victoria, August 18, 1914.

[47] Fayle, Seaborne Trade, I. pp 154 & 164.

[48] She came to protect waters which Canada had undertaken to defend, and there was irony in the fact that she belonged to the Bristol class. The Canadian naval programme of 1910 had included four Bristol class cruisers, of which two were to have been stationed on the Pacific Coast.

[49] Hdq, to Hose, August 18, 1914 (two signals). Copies in N.S.R. 1047-19-3(1)

[50] Colonist, Victoria, August 11, 1914.

[51] Senior Naval Officer, Esquimalt, to Hdq., August 19, 1914. N.S.R. 1047-19-3(1)

[52] Hose to Hdq. August 23, 1914. N.S.R. 1047-19-3(2)

[53] Admiralty to Commander-in-Chief, July 17, 1898. “Records of North Pacific Naval Station, “Dominion Archives, MS Room.

[54] The proceedings of the Newcastle described in this paragraph are based on Fayle, Seaborne Trade, I, pp 229-230.

[55] Colonist, Victoria, August 22, 1914.

[56] Kreuzerkrieg, Vol I, dispels all but a few remnants of the fog which formerly hid most of the movements of the Leipzig and Nurnburg during August and September, 1914.

[57] Kreuzerkrieg, I, p 349 (translation).

[58] Ibid, p 347

[59] Ibid, p354. In 1917 the Admiralty published a chart which showed the Leipzig’s track running north as far as Cape Flattery. A British official chart published immediately after the war, however, shows her as “Cruising off S. Francisco Aug. 11th-17th.” (See Corbett, Naval Operations, I, (Maps), no.14.) There seems to be no reason for doubting the accuracy of the German official history on this point. It is true that none of von Spee’s ships got home; nevertheless, the Leipzig had opportunities for reporting her movements to the German consul at several places, including San Francisco, and no doubt she did so. Four of her officers, moreover, survived the battle of the Falkland Islands.

[60] Ibid, p 357.

[61] The Leipzig’s movements, September 11021, are described in a personal account by the master of a captured British merchant ship. See (British Official History) Archibald Hurd, The Merchant Navy, I, London, 1921, pp 180-184.

[62] This brief account of the operations of von Spee and his opponents is based upon Kreuzerkrieg, Vol I; Sir Julian Corbett, History of the Great War – Naval Operations, revised edition, Vol I, London, 1938; and A,W. Jose, The Royal Australian Navy(The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914 – 1918, vol IX,) Sidney, 1928.

[63] Grand-Admiral von Tirpitz, My Memoirs, London, n.d., 1919, II, p 351.

[64] Four midshipmen of the Royal Canadian Navy, serving in H.M.S. Good Hope, lost their lives at Coronel.

[65] Report of the Commissioner concerning Purchase of Submarines, (Davidson Commission), Ottawa, 1917, p11.

[66] Fayle, Seaborne Trade, I, pp 162 and 179.

[67] Hose to Admiral Kingsmill, November 9, 1914., N.S.R., 1047-19-3(2)

[68] Kingsmill to Hose, November 10, 1914, Copy Ibid.

[69] Telegrams and letters in N.S.R. 1048-10-25

[70] Hose to Hdq,, October 31, 1914., N.S.R. 1-1-19

[71] Extracts of Letters f Proceedings in possession of Commander Haines.

[72] See G.N. Tucker, “The Organizing of the East Coast Patrols.” 1914-1918. In the Report of the Canadian Historical Association, Toronto, 1941, p35.

[73] Corbett, Naval Operations., I., pp 426-427.

[74] Fayle, Seaborne Trade, I., pp 162-163.