The Negotiations to Relocate the Songhees Indians, 1843 – 1911.

Jeannie L Kanakos

BA, Simon Fraser University, 1974.

Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts

in the Department of History.

Jeannie L Kanakos 1983

Simon Fraser University

April 15, 1982

All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or any other means, without the permission of the author.

Note: Hallmark Heritage Society received permission from Jennie L Kanakos to reproduce this material by email message, October 14, 2016.

ABSTRACT

In 1911 the Songhees Indians surrendered their reserve in the heart of Victoria City. They were relocated after nearly 50 years of negotiations. An examination of ethnographical and historical information has revealed the Songhees’ active role in negotiations for their land. The Songhees resisted the removal, and their position was a stumbling block to the conclusion of the transaction.

The Federal and provincial governments were caught in a jurisdictional battle over Indian land in the province of British Columbia. The question of the Songhees relocation exemplified the complex dispute between the governments under pressure from their electorates the governments seriously attempted to solve the relocation question, but the Songhees’ refusal to surrender their reserve delayed a conclusion to the removal transaction. If the Songhees had not resisted removal, they might have been relocated on numerous occasions between 1880 and the first decade of the twentieth century.

As internal and external conditions changed for the band, and under the leadership of a Chief who saw that the time was right for a move, the Songhees agreed to surrender their reserve. They agreed to move according to terms which in some measure reflected their own needs. The terms – mainly a large cash settlement – required special legislation. The Songhees’ resistance to moving and their participation in land negotiations were influenced by their long-standing relationship with the environment, and especially with their land.

PREFACE

In the history of Indian European relations in British Columbia, the Indian land question is a complex and crucial area of inquiry. The debate over the Songhees’ land is one example which testifies to this. The protracted negotiations to relocate the Songhees demonstrates the complexity of Indian European as week as federal provincial relations regarding Indian land in British Columbia. The history of the Songhees Reserve also elucidates the impact of the debate at the band level. Historians writing on these complex aspects of the land issue have, for the most part, failed to recognize Indian input in this debate over their land. [1] The view of Indians as incidental or peripheral has, until recently, pervaded the histories of British Columbia and Canada.

Historians are now attributing a more active role to the Indians. Anthropological data have facilitated this approach. A synthesis of anthropological and historical information has provided a basis for a more comprehensive analysis of the interactions between Indians and Europeans. Such a synthesis has revealed an active role on the part of the Indians in the fur trade, as well in their relations with missionaries.[2]

One of the purposes here is to establish the role of the Songhees in the negotiations to relocate their reserve. To do so, it is necessary to examine the pre contact song keys society, particularly their relationship with their land. Anthropological evidence reveals that the Songhees, living in a unique geographical setting, developed an intimate relationship with their territory. The Songhees economy was dependent upon the availability of particular resources at specific times of the year, and their migratory lifestyle was integrated with their system of land use and site ownership. Most of the Songhees’ culture was influenced by the demands of their economy.

The construction of Fort Victoria in the centre of Songhees’ territory challenged the Songhees traditional relationship with their land. They seem this challenge, and the accompanying threat posed to their survival through the introduction of alcohol and new kinds of disease, the song he’s adapted their economy to that of the Fort and generally responded in an accommodative manner to European penetration into their territory.

In the three decades following the establishment of Fort Victoria, Songhees European relations appeared agreeable. The Songhees were employed at the Fort and acquired new wealth. They also continued their traditional migrations to gather food and resources. During this. The Songhees and Europeans negotiated several land deals. These included: the relocation of a village, the relinquishment of aboriginal title, and a leasing program. Evidence of the Songhees role in these negotiations is very sparse, but documentation from a later period reveals Songhees’s discontent with previous land transactions. Department of Indian affairs correspondence indicates that the Songhees refused to negotiate any further relocation until they received payment for the lands they had already sold and leased.[3] A breach of trust was at the root of the Songhees suspicion of negotiations regarding their land. After the gold rush, the Songhees became aware of the implications that settlement had on the availability of resources in their territory. These factors caused the Songhees to abandon their accommodative response for one of resisting attempts to remove their reserve.

In 1871, when British Columbia entered confederation, Indian affairs became a federal responsibility. The Songhees reserve question became one of the many contentious issues in the debate between the provinces and the dominion regarding Indian land in British Columbia. The crux of the debate was the disagreement over the interpretation of relevant sections of the Terms of Union and the British North American act. In the case of the Songhees reserve, however, the governments agreed to overlook these disagreements in order to conclude a relocation agreement. Each government did so because of its own political reasons: the provincial government was faced with mounting pressure for land from a growing population had a developing resource based economy, while the federal government was concerned with support in the West in the upcoming 1911 election.

While the prolonged debate was due, in part, to the government’s difficulties in agreeing to terms for the Songhees removal, the Songhees also played an important role in the negotiations. On numerous occasions when a deal between the governments was close at hand, the Songhees refused to even discuss relocation. Their surrender was required by the Indian act, and the Songhees refusal to discuss such a surrender, If the Songhees had not resisted relocation, they might have been moved in 1880, 1891, 1895, or on numerous occasions in the first decade of the 20th century. The Songhees opposition to relocation was related to distrust engendered from previous land deals, but the Songhees also resisted relocation because they enjoyed many features associated with their city location. The key advantage for these Songhees was the economic opportunities available in the urban centre.

At the turn of the 20th century, when the advantages of the urban locale began to decline, Lee Songhees’s resistance to relocation wavered. At this time, the band faced mounting pressure for their removal. Despite this challenge the Songhees were able to influence the final deal. The Songhees chief, who was interested in his own financial add vantage as well the Band’s, held out for a cash settlement paid directly to Songhees families. This demand required special legislation in the House of Commons, the legislation, the Songhees Reserve Bill, is one example of government response to the Songhees position.

While the Songhees resisted removal and delayed a settlement of the issue, the government held the balance of power. The dominion was willing to meet the demands of the Songhees band but it demonstrated its power to influence Indian matters when it amended the Indian Act so that in the future, Indians would not be allowed to impede urban development.

In conclusion, the Songhees were not passive but played an effective role in the relocation negotiations. Though their initial response to land arrangements was positive, this response soon turned sour. They resisted relocation as long as they could. The Songhees lost their city reserve, but not without a fight. Their active role required the governments to take the Songhees position into consideration when negotiating a settlement.

This type of consideration was important for historians writing on the Indian land question. Though not necessarily considered so in the past, the Indian role is a vital component in the history of the Indian land debate. Only after the Indian is written into this history, can historians begin to make the comparisons and conclusions which may lead to a deeper understanding of the Indian European relations over land in British Columbia.

Chapter One: The Songhees Indians and Their Land.

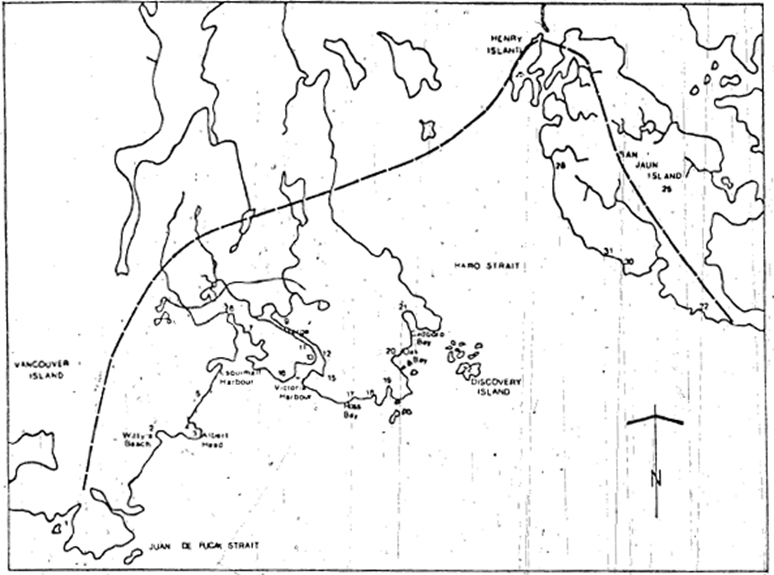

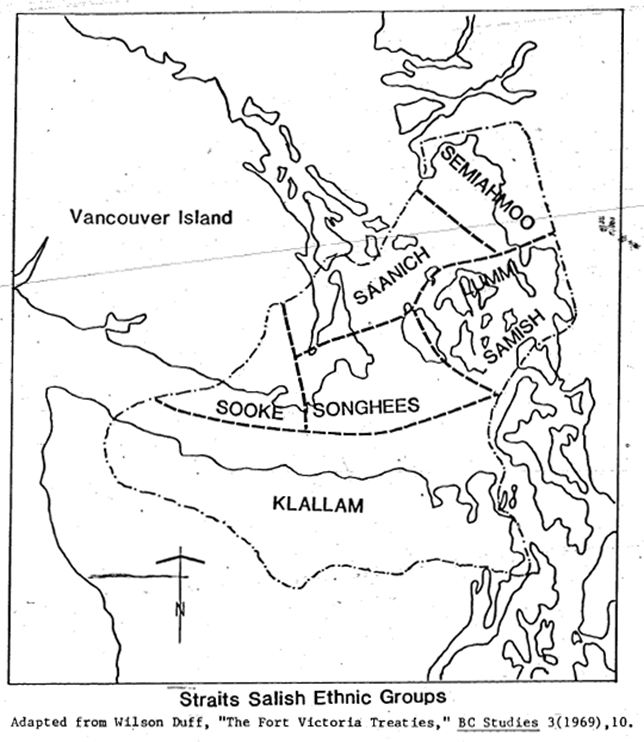

The Songhees Indians are a group of coast Salish Indians who inhabited the southern tip of Vancouver Island, Discovery Island, and the eastern shores of Henry and San Juan Islands[4]. They had experienced indirectly the European presence on the coast for numerous decades and with the construction of Fort Victoria in 1843 the Songhees made direct contact with a culture very different from their own. The contact experience was an event which led to adjustments in the Songhees relationship with their environment and changes in their culture.

An investigation of the role of the environment represents an important emphasis in anthropological inquiry[5]. Calvin Martin discusses is this approach and draws out its implications for historians of Indian European relations[6]. Martin recommends that the historian view European penetration into a group’s territory has an event which triggers a series of adjustments in the group’s relationship with the environment[7]. The details of the Songhees territory and their use of their geographical space in prehistoric times are essential to an understanding of the impact of contact on their culture and their relationship with the land. The ethnographic data on the Songhees and their environment have strengths and limits which, at the outset, must be clarified.

Four well known anthropologists have collected ethnographic data on the Songhees Indians[8]. Franz Boas presented his summary of data on the “LKungen” or Songhees, in 1890 as part of his” Sixth Report of the Committee Appointed to Investigate the Physical Characteristics, Language and Industrial and Social Condition of the Nort-Western Tribes of Western Canada.” His report was an overview of Songhees culture as part of the coast Salish stock. It focused on major cultural aspects such as customs, beliefs, and organization, but it did not answer many questions regarding Songhees’s daily life. Boas Did not deal with the system of decision-making and leadership and he did not name his informants in the report.

Charles Hill-Tout did field work among the Songhees in 1907, approximately twelve years after Boas. Hill-Tout summarized his field data in the report on the “Ethnology of the southeastern Tribes of Vancouver Island, British Columbia.” His work differed from Boas’ work on minor points, and his summary was, in the main, a description of the Songhees language[9]. Hill-Tout’s report, like Boas’ did not describe the Songhees daily life. Both Boas and Hill-Tout provided some information regarding the Songhees relationship with the land, but neither discussed this subject in detail.

The most extensive study of the Songhees is Wayne Suttles’ “The Economic Life of the Coast Salish of Haro and Rosario Straits”, written in 1951. Suttles described the Songhees as part of the Straits Salish cultural unit. He explained that certain cultural traits were common to the Straits Salish as a whole due to their particular geographic location and its resources. Suttles the subsistence activities of the Songhees as one group of the Straits Salish, and he elaborated are the religious and social customs of these people. His informants agreed with most of the information given to Hill-Tout and Boas. Suttles Incorporated field work pertaining to the Songhees neighbors from Erna Gunther’s “Klallam Ethnography” and Diamond Jenness’ manuscript, “The Saanich Indians of Vancouver Island[10]”. Suttles enhanced his ethnographic data with information contained in United States government documents.

Writing on the Songhees in “The Fort Victoria Treaties”, Wilson Duff drew information from settlers reminiscences, travelers accounts, newspaper articles, government documents, and that data from Songhees informants. In this article, Duff analyzed the treaties signed by the tribes of the South eastern tip of Vancouver Island at James Douglas in 1850. Duff argued that these documents contained insights into, as well as distortions of, the pre- contact environment of these Indians. Duff compared his own findings regarding specific places indeed Songhees’s territory with those of Suttles, Hill-Tout and Boas. His work is a valuable synthesis of ethnographic data on the Songhees territory prior to the construction of Fort Victoria.

The data collected by archaeologists such as Harlan Smith is relevant to both anthropologists and historians of the coastal Indians.[11] Contemporary archaeological research has added to the understanding of the prehistory of the Songhees territory. Two major contributors are Donald Mitchell and Roy Carlson.[12] The area of southeastern Vancouver Island remains important to archaeologists attempting to reconstruct the prehistory of the general area of the southern coast of British Columbia[13].

Both anthropologists and archaeologists experienced difficulty collecting data in the Songhees territory. The Songhees were exposed to European culture indirectly from at least 1774 and as a daily reality from 1843, Thus ethnographic information collected to recreate a pre- contact environment was influenced by this long standing interaction with Europeans. Furthermore, many other Indian groups from the northwest coast travel to Fort Victoria camped among the Songhees while they traded goods and visited the Fort[14]. At times, as many as 2000 Indians were living amongst the Songhees. As an Indian agent pointed out, many of the characteristics attributed to the Songhees in reality belonged to these visiting Indians.[15]

Taking into consideration the strengths and weaknesses of the ethnographic literature, it is possible to describe the main features of the Songhees culture. It is important to note that the following description is not intended as a detailed report but will attempt to draw out the essence of the Songhees culture as described by the noted anthropologists. The elements examined will include the Songhees worldview, social organization, and ceremonies. Is examination will focus on a major thread running through these complexes, the Songhees relationship with their environment. The intent is not to emphasize one or another cultural aspect, for most are inter dependent, but rather to highlight those related to the Songhees relationship with the environment.

The Coast Salish Songhees spoke “Lakonenan”[16]. They shared this language with their immediate neighbors the Semiahmoo. Lummi, Samish, Klallam, and Sooke Indians. The Songhees interacted primarily with these similar linguistic groups although the Songhees became a separate political unit in the eyes of the Europeans, with the signing of the treaties in 1850. Songhees’s social contacts extended to other coast Salish groups such as the Cowichan, Squamish, and Musqueam[17]. These interactions took the Songhees out of familiar territory to the Cowichan Valley on Vancouver Island, to the mainland coast, and to the lower reaches of the Fraser River.

The Songhees shared a common world- view with their coast Salish neighbors. These groups possessed a world- Vue which depicted a spiritual relationship between man, nature, and the supernatural. The Songhees envisioned nature as a source of supernatural powers, and they saw food as a gift of the supernatural. Both supernatural power and food were greatly revered. Food was often described by a word which means “sacred.[18]” has the Songhees moved over their territory and collected resources they did so with reverence and attempted to main positive relations with the living spirit in all things.

The Songhees shared a common world- view with their coast Salish neighbors. These groups possessed a world- Vue which depicted a spiritual relationship between man, nature, and the supernatural. The Songhees envisioned nature as a source of supernatural powers, and they saw food as a gift of the supernatural. Both supernatural power and food were greatly revered. Food was often described by a word which means “sacred.[18]” has the Songhees moved over their territory and collected resources they did so with reverence and attempted to main positive relations with the living spirit in all things.

According to Suttles there were three classes in the Songhees society. The “high class people” who are “people with advice” or “who knew how to behave properly”. The “second class people” or poor people who had become rich. He “low class” people were those without advice or those who had “lost their history”[19]. Boas called these classes the nobility, the middle class, and the lower class[20]. Boas claimed that the lower class lived in the southern area of the Songhees territory. Perhaps the low status of these groups was related to the fact that this area was without established reef net locations. Hill- Tout, named four “castes” among the Songhees: they “chieftains,” “hereditary nobility,” “untitled” and “slaves”. Hill-Tout Stated that each of these classes also had its own name. A common man could not use a middle-class name, but he could become a middle-class person by sponsoring feasts. Chiefs were considered high class persons. The chiefship was passed from father to son, preserving this noble position as inherited[21].

The nuclear family was the basic unit for production and consumption in the Songhees society. Families live together in long houses, and each family occupied a separate section of the house. The family groups living together were related by “blood or by marriage either through the males or the females.[22]” well each family had its own fire in the house, some of the food preparation was done communally. These families work together in some major food gathering activities. They also participated as a unit in trading possessions, sponsoring ceremonies, and for defence[23]. A detailed description where the Songhees families lived in winter and in summer is presented later in this chapter. )

Wealth, power, and knowledge were possessions which contributed to an individual’s or a families’ rank[24]. Wealth was acquired through the inherited possession of a productive food site and by way of successful hunting expeditions. Success on a hunting expedition was based on hunting expertise and the possession of hunting knowledge and powers[25]. While upward mobility was possible through the acquisition of power and knowledge in visions and dreams, rank was this usually established through the inheritance up these possessions[26]. Power and rank were validated by a display of wealth. The sponsorship of ceremonies such as marriage feasts and potlatches provided an opportunity for their display.

Songhees’s marriages were arranged by the families involved rather than by the couple. Marriage was the “primary alliance” between households and communities[27]. The ceremony included a display of wealth and exchange of goods. In most cases women were recruited from neighbouring straits Salish and coast Salish communities. Care was taken to ensure that the status and wealth Of the families were comparable. Marriages of close family memberships were not encouraged but marriage beyond second cousins was permissible[28]. If one partner died, then the survivor usually married a relative of the deceased, so that the familial ties the marriage represented were maintained[29]. Polygamy was practiced, especially amongst males of high rank. In many instances, the male had wives in several villages therefore establishing ties with each group[30].

The most elaborate Songhees’s ceremony was the potlatch. A potlatch was usually sponsored by a chief, who decided which of the neighbouring tribes would be invited. During the ceremony, the hosting chief was raised on a scaffold while his son or daughter danced, then the gifts were distributed[31]. The distribution could take three of for days, and was interspersed with games, dancing and eating[32].

The resources collected throughout the year were shared with the guests at the Songhees ceremonies. The resources accumulated formed the basis of a family’s wealth. With a plentiful harvest a family was able to perform an ostentatious display of wealth, whereas in a lean year a display might be restricted. An abundance of resources also provided a surplus for trading. A limited supply of resources might reduce the social standing of a particular family or group.

To fully understand the changes in the Songhees; relationship with this environment after the construction of Fort Victoria, it is necessary to establish a clear picture of their environment prior to contact. This picture contains interdependent variables such as the territory, habitation locations, resource sites, and methods of exploitation. Included in this description are the variations regarding place names and locations which contribute to a picture as complete as possible. The location of the winter villages, summer camps, and resource sites demonstrates the Songhees settlement patterns and subsistence systems.

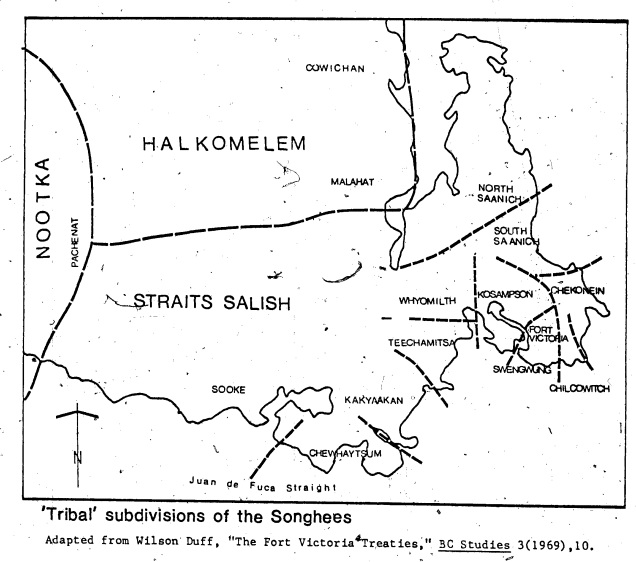

Before the construction of Fort Victoria, the Songhees territory included the eastern tip of Vancouver Island from Cordova Bay to Parry Bay, Discovery Island, and the western shores of Henry and San Juan islands. There is a discrepancy regarding the southern boundary at Beecher Bay. Boas did not locate any Songhees winter villages here, but Hill-Tout named three groups of Klallam origin who lived at Beecher Bay[33] and according to Gunther’s informant the Klallam moved to this location after the construction of Fort Victoria. Evidently a Klallam man named “Yokus”, left Port Angles about 1865, and attempted to settle his family on the west shore of Beecher Bay. After a quarrel with the Sooke, who claimed the territory, the Klallam group first returned to Washington, then moved to Beecher bay’s east shore[34]. Suttle’s informant told him that the Klallams moved initially to the edge of Fort Victoria to make shingles and plant potatoes for the Europeans. When the young people began to consume alcohol, the Chief moved the group to Witty’s Beach[35]. However, Suttles located one of Boas’ Songhees winter village sites here, because his informants told him that the Songhees family was named “K.ek.a’yekZn” lived there, before the Klallam[36]. Whether or not this group of Songhees abandoned Witty’s Beach, in favour of the village on the edge of Fort Victoria at the time of its construction is unclear.

The southern edge of the Songhees territory, according to the “Teechamitsa” Treaty and Duff’s informants was Albert Head[37]. In the territorial description of the first land purchase of James Douglas in 1850, the Teechamitsa occupied the “whole of the lands situated and lying between Esquimalt Harbour and Point Albert including the latter, on the Straits of Juan de Fuca and extending backward from thence to the range of mountains on the Saanich arm about ten miles distant[38].” Duff, Suttles and Gunther agreed that the area south of this belonged to the Sooke Indians prior to contact, and to the Klallam Indians after contact.

As noted by Duff, Songhees boundary lines were not as static as the Fort Victoria treaties suggested. The Klallams movement in and out of what might have been the southern edge of Songhees’ territory, indicates that the Songhees shared their territory with neighbouring Straits Salish groups. The northern boundary of the Songhees territory was also unclear. While Cordova Bay was named as a Songhees village[39], Douglas allotted the territory encompassing this village to the Saanich who signed a purchase agreement in 1852, two years after the Songhees signed treaties[40].

Songhees habitation sites included permanent winter villages and temporary summer locations. Winter villages were comprised of several longhouses. The size and positioning of the houses depended on the defense requirements of the location[41].

Approximately thirteen winter village sites existed in Songhees territory. They were not all occupied at the time of Fort Victoria’s construction. The Songhees population, like many other coast tribes had been reduced by small pox epidemics and warfare before the construction of the fort[42]. Also, villages were abandoned when family groups amalgamated at one village for social or economic reasons[43].

The most southerly winter village was Stangal, which was located by Boas and Hill-Tout, just north of Albert Head[44]. Boas named the group the “Stanges”, while Hill-Tout named the group “Sones”[45]. However, Suttles located this group closer to Esquimalt Lagoon, and he did not attribute a specific site to these people, who were known as the “lowest people,” in the territory[46]. Both possible Stanges locations were also within the territory described in the Teechamitsa Treaty[47]. Boas reported that the name” Songhees” was an anglicization of “Stanges”[48]. One can only speculate why the name “Songhees” was derived from that of the lowest ranking Songhees group.

Just north of Stanges was the village Stchilikw. This site was named by Duff’s informant as a village on Mill Stream[49]. Neither Suttles, Hill-Tout, nor Boas, named this as a village site. If it existed, it was in the area described in the treaty signed with the group Douglas named the “Whyomilth”[50]. According to the treaty this group occupied the lands “between the north west corner of Esquimalt, say from the island inclusive, at the mouth of the saw-mill stream, and the mountains lying west and north of that point: this district being on the one side bounded by the lands of the Teechamitsa and on the other by the lands of the Kosampson family”[51]. As Duff noted, eighteen men made their mark on the treaty, indicating that there was at least one village site in this territory[52]. Both Duff and Suttles that the name Esquimalt was probably derived from the phrase “vicinity of the village of the Whyomilth”[53], a further indication of the possibility of the location of a village on the shore of the inner reaches of Esquimalt Harbour. This village, wherever it was, was probably abandoned either prior to or at the time of the construction of the fort.

The site Kalla was named by Duff’s informant as belonging to the “Kosampsom of the 1850 treaty[54].” Duff placed this village on the northern side of Plumper Bay, where Douglas showed an Indian village in his 1842 map[55]. Suttles located this village which Boas called “Qsa’psEm” slightly south of Plumper Bay, closer to Constance Cove, but did question the precise location[56]. Hill-Tout recorded that the Qsa’psEm village was on the Gorge and Duff located this village at the site of “old Craigflower school[57]. Duff’s informant stated that the people who loved here spoke a slightly different dialect[58]. Hill-Tout also located a Qsa’psEm village on the south side of James Bay. He stated that after the fort had become a “populous centre” Douglas “transplanted the village of Qsa’psEm, who dwelt near the spot where the parliament Buildings now stand, to Esquimalt Harbour where a remnant of this tribe still lives”[59]. Duff’s informant named the “Parliament Buildings” site “S kosappsos”[60]. Whether this was a village prior to contact is unclear. It was allotted as a village site after the treaties were signed and was depicted on maps as an Indian reserve until 1854[61].

One of Duff’s informants recorded the site at Gorge Park as being the previous village of the Swengwhung who moved to Fort Victoria during its construction[62]. Another of Duff’s informants, like Suttles’ , and Hill-Tout’s gave this name for the “new groups” of people who formed the village on the edge of the fort at the foot of Johnson street[63]. Hill-Tout stated that:

After the founding of Victoria, first called Camosun, after the Indian name of the rapids on the Gorge, the natives flocked into the harbour and settled on what is now the foot of Johnston Street. They were known as the Swinhon and were composed of members of the various outside villages. This became a populous center and, so populous, indeed, to inconvenience the colonists, and Governor Douglas induced them to cross the bay and settle on the other side, where there has been a mixed settlement ever since. Known as the “Songish Reserve’[64].

As Duff noted, at the time when the treaties were signed, the Kosampson were living at the Parliament Buildings” site and the Swengwhung had been moved to the New Songhees Village across from the fort. Duff pointed out that Douglas must have “judged the Swengwhung claim stronger than that of the Kosampson as owners of the Inner Harbour[65]. The boundary between the Swengwhung and the Kosampson described in the 1850 treaty, though it does not agree with this ethnographic data, was through Deadman’s Island, and the upper part of the Inner Harbour. Duff hypothesized that both the Kosampson and the Swengwhung wintered on the Gorge and that despite the existence of the Kosampson village at the “parliament Buildings” site they were allotted territory on both sides of the Gorge north of Deadman’s Island while the Swengwhung were said to have the area of the Inner Harbour[66]. Boas alluded to the “Squingun” as one of the original Songhees groups living at Victoria. Whether the Swengwhung were a unique group prior to contact as the Swengwhung treaty, Boas and one of Duff’ informants suggest, or whether they were a “new group” made up of members from all the villages as Hill-Tout, Suttles and another of Duff’ informants claimed remains undecided.

The moves of the Swengwhung are also unclear. Perhaps “across the bay” as described by Hill-Tout meant across James Bay rather than across the Inner Harbour. There is a possibility that when the Swengwhung were asked to move in 1843, they moved across James Bay to the legislative buildings site and remained there until the mid 1850s, then sold their reserve and moved to the site referred to by Hill-Tout. A second scenario is that when requested to relocate, some Swengwhung moved to the Legislative Building site, and some moved to the site across the Inner Harbour. However, sometime in the mid 1850s, the Songhees sold the Legislative Buildings site and relocated either on the west side of Victoria harbour or on Esquimalt harbour[67].

The archaeological data presented by Harlan T. Smith, who worked in the Victoria area at the turn of the century, supports Duff’s thesis. Smith stated that shell heaps, a sign of a possible village site, existed regularly on the southeastern tip of the coast of Vancouver Island[68]. He also stated that “following the north side of the Gorge (Portage Inlet) from the Gorge Bridge to the Craigflower Bridge, a distance of more than a mile there is an almost continuous shell ridge[69].” Smith recorded that numerous implements were found in the vicinity of Victoria indicating the presence of Straits Salish in the area[70].

To the north of Victoria Harbour a winter village was located at Ross Bay. There is some uncertainty from differences in spelling, but Suttles noted that one of the four groups Boas located at “McNeil Bay”, actually lived at Ross Bay[71]. Hill-Tout stated that the “TciaKa’utic” lived around Ross Bay[72]. Duff’s informants named Ross Bay and Clover Point “Wholaylch”[73].

Suttles also placed a winter village at Gonzales Bay. He hypothesized that one of he villages named by Boas corresponded to the village on this bay[74]. Duff’s informants concurred with this and added that the group who owned Gonzales or Foul Bay also owned McNeil Bay[75]. Also called “Shoal Bay” , McNeil Bay was named as the site of a winter village by Duff, Suttles, Hill-Tout and Boas[76]. Duff’s informants associated this bay with both the Chilcowitch and Chekonein groups who signed treaties with Douglas. Duff pointed out that if these groups shared or exchanged sites at McNeil and Gonzales Bay, then it occurred prior to contact for both groups lived at Cadboro Bay when Douglas began constructing the fort[77].

Suttles and Boas located winter villages at Oak Bay[78]. Suttles’ informant was vague about when the village existed. Harlan Smith cited Gregon C. Hastings’ findings indicating that an “embankment” and a “ditch” existed on the Bay[79]. Smith found numerous shell heaps along the shores of Oak Bay[80]. Both of these formations were clues of permanent habitation in the vicinity. Duff’s informants named this location “Sitchanalth” which means “Willows Beach.” Perhaps the village was once occupied by either the Chilcowitch or the Chekonein who, as Duff hypothesized joined forces to form the Songhees village on Cadboro Bay[81].

Boas, Hill-Tout, and Suttles agreed that Cadboro Bay was the location of a winter village site[82]. Smith concurred as he recorded the existence of “an embankment and a ditch” as was as a “trench” at Cadboro Bay. He stated that, “on a point cut off by the trench he found “traces of house sites’ and “the remains of a comparatively recent cooking place.[83]” Smith also found “several hundred cairns” or burial places on the land “sloping eastward towards Cadboro Bay”[84]. Crediting the research done by a colleague, Smith stated that” besides the numerous shell heaps Dr. C.T. Newcombe discovered an “earth work” along the “northeast shore of Cadboro Bay”[85]. The archaeological data point to the substantial Songhees population who inhabited Cadboro Bay. Duff asserted that this was the site of the principal Songhees village and that this group was the highest ranking of the Songhees families[86]. Duff hypothesized that that the bay was shared by the Chilcowitch and the Chekonein at the time of contact. Duff believed that Douglas considered these groups, particularly the Chekonein, the most prestigious among the Songhees. Douglas, Duff claimed, bartered with the Chekonein after all other Songhees treaties had been signed. He paid three of the leading chiefs of the Chekonein including “King Freezy” more blankets than any other of the leading chiefs[87]. At the time of the construction of Fort Victoria, these families moved to the edge of the fort, to the village site at the foot of Johnson Street.

Boas, Hill-Tout, Suttles and Duff also agreed that there was a permanent village on Discovery Island[88]. Suttle’s informant stated that the group lived on the Fort Reserve until the 1862 smallpox epidemic, then they returned to Discovery Island. After the disease passed some Songhees returned to the Songhees fort reserve and some remained on the Island. Though the Chekonein treaty did not include Discovery Island[89], Duff included this Island household as part of the conglomerate of families who inhabited Cadboro Bay at the time of contact[90]. Smith found numerous burial sites here, reinforcing the probability of Songhees occupation of Discovery Island[91].

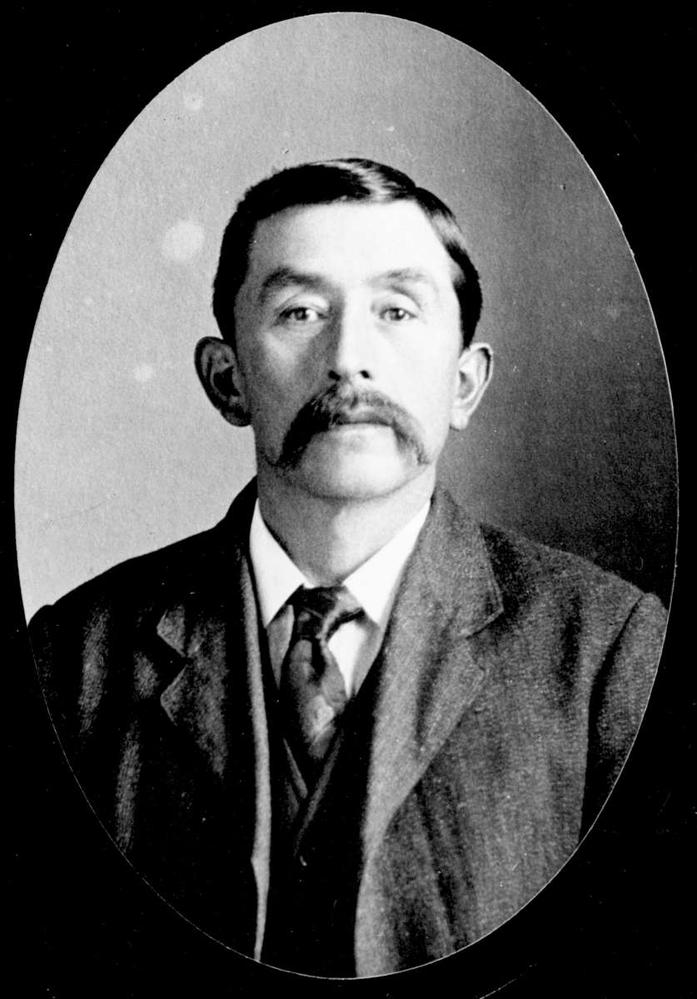

Only Suttles indicated the possibility of winter village sites on Henry and San Juan Islands[92]. The existence of the latter is substantiated in Department of Indian Affairs correspondence[93]. In a band census compiled in 1910, several Songhees, including the Chief, Michael Cooper, traced their ancestors to San Juan Island[94].

The winter villages were important in the lives of the Songhees. The longhouse provided safe and warm relief during a long and cold winter season. Inside the “big house” through dance and celebration, the spirits came alive with the sounds of drums and chanting. Here, near the warmth of the fire, Songhees families passed the winter months. Perhaps more important, these winter villages combined with the summer camp sites demonstrated Songhees ownership, through occupation, of the numerous bays situated on the southeast coast of Vancouver, Discovery, Henry, and San Juan islands. Though there are discrepancies on the exact location of the Songhees villages, anthropological and archeological evidence indicates a well-established occupation of this territory.

The Songhees traveled from their winter villages to their summer camp sites by canoe. According to Boas, two types of canoes were employed. One was a square- boat canoe that was used for reef netting sockeye. The other was a less common war canoe[95]. Suttles added a third type named the saltwater canoe[96].

The Songhees temporary summer campsites generally corresponded with the song he’s reef netting locations. Most of these sites existed on San Juan island. For instance, there were two reefnetting sites located on Andreas Bay, one at Deadman Bay, one at Kanaka Bay, and one just to the north of Kanaka Bay . The most southerly summer camp was at Eagle Cove where a reef netting site also existed[97].

Suttles indicated which of the Songhees families owned these temporary camps. He linked these Songhees at Ross Bay with summer camp and reefnetting sites at Eagle Cove and he linked the Songhees of Gonzalez Bay with the Andrias Bay camps. The McNeil Bay Songhees according to Suttles summered at Deadman Bay where one reef net site was located. Kanaka bay was owned by the Songhees on Discovery Island[98]. Several reef netting locations existed on the western shore of this island, which might account for the wealth and prestige of the San Juan Songhees Besides the summer villages associated with the reef net sites on San Juan island, Suttles reported the existence of several other campsites. He also located a temporary camp on Henry island though there was not a reef net site here[99].

The only reefnet location on Vancouver Island was named Mukwuks, at McCauley Point[100]. Suttles map showing food source locations does not indicate that sockeye were available at Mcauly Point. It is apparent however, that until 1890, the Songhees were salmon fishing both inside and outside Victoria Harbour. Federal Fisheries regulations instituted in the early 1890s prohibited fishing in the harbour[101], but McCauley Point might have been a reefnet location prior to these regulations.

Reefnetting was a method of fishing that was the speciality of the Straits Salish. Dependent upon unique geographic features, reefnetting influenced technical, religious, and social facets of the Songhees culture. The techniques of reefnetting were based on a knowledge of the migrations of the sockeye salmon through the straits where the particular topography facilitated this type of fishing[102]. A net made from cedar twine was suspended between two canoes over a reef where the water was shallow and clear. To bring the fish to the surface in the net, a draw-string rope, which was anchored with stones, was pulled, closing the net[103], The fishing procedure, like most other food gathering activities of the Salish, was accompanied by rituals. Specific ceremonies were presided over and organized by the chief who owned the fishing site. Salmon were considered a sacred gift from the supernatural. The salmon themselves processed a spirit which was revered[104]. Special care was taken when killing and drying the salmon, so that the salmon’s spirit was not offended.

Fishing was done by men, while women and children assisted with cleaning and drying salmon. In return for the labour supplied at the fishing site, families received food throughout the fishing season[105]. A reefnet site owner could recruit from all of the tribe. Productive sites were popular and there was competition amongst the Songhees for work at these sites. Also, some owners hared more of the catch with the workers than others, which affected the desirability of working with one site owner or another[106].

The summer reefnetting activities had social implications for the Songhees. Reefnetting brought families together in close contact. Groups and individuals, who otherwise might not associate throughout the year, participated in the religious and social ceremonies related to this subsistence activity. Social relationships developed and marriage alliances were considered. The possibility of spontaneous social interaction was probably greater at this time, than during the winter season[107].

Though reefnetting was the most important economic activity, the Songhees travelled to many other food sites, especially in the summer[108]. The Songhees, like their Straits Salish neighbours, adapted their migratory patterns to the availability pf particular food sources at specific times of the year. Sites were frequented in a particular order depending on which berries, rushes or roots were in season. For example, Whosykhum, a site west of where the Empress Hotel now stands, was a camas root bed. Indians travelled regularly to this location[109]. This might account for the depiction of Indian canoes travelling in James Bay, in the first pictures and maps of the Fort[110].

Other foods the Songhees gathered included bulbs, sprouts, and stems[111]. The Songhees also gathered shellfish, mussels, oysters, and clams represented just portion of their annual harvest from the sea[112]. The Songhees also trolled for coho salmon and hunted ducks[113]. The variation and abundance of resources provided a stable and affluent economy. The ownership of these resource sites provided individuals and families with wealth which was used as a means of verifying rank, and which influenced the procession of power. Thus, environmental conditions influenced social stratification.

The numerous habitation and resource sites in the Songhees territory indicated Songhees precontact land use and land ownership. Winter villages were owned by families who built and occupied them, while resource sites were owned by individuals. Summer camp sites were bult and occupied by those engaged in nearby reefnetting activities. The rest of the territory was shared amongst the Songhees and their Straits Salish neighbours.

Although Europeans might have judged the territory available for settlement because it was not completely occupied or cultivated, according to the ethnographical and anthropological evidence this was not the case. The preceding survey of Songhees village sites, resource sites, and ceremonial locations shows the extensive use they made of their territory. Moreover, not only the Songhees but also their Straits Salish neighbours depended upon the resources of this environment.

The importance of the environment to the Songhees cannot be understated. Their territory and its resources were inseparable from their world view and culture. Anthropologists and Indians who believe the influence of the environment to be paramount, might say “the land is the culture[114].” Only with an understanding of the Songhees relationship with their environment and its role in their culture can one begin to appreciate some of the sources of the Songhees-European conflict over the Songhees land.

Chapter Two

Songhees-European Relations 1843-1871.

From the time of Fort Victoria’s original construction in 1843 until British Columbia entered into Confederation in 1871, Songhees-European relations appeared to be relatively harmonious. At contact, the Songhees adapted in a way that accommodated their own needs and aspirations as well as those of the Europeans. However, the relations between the Songhees and the Europeans especially regarding land soon became strained. These strained relations eventually led to Songhees resistance to any further dispossession of land. By the time the federal government assumed responsibility for Indian affairs in British Columbia, the Songhees were adamant about resisting relocation.

On June 28, 1842, the resolution was passed and changed the lives of the Songhees forever. On that day, the Hudson’s Bay Company chose a new site for its headquarters on the Northwest Coast. The Company’s Counsel of Northern Development decided that:

….. it is being considered in many points of view expedient to form a depot at the Southern end of Vancouver’s Island, it is resolved that an eligible site for such a Depot be selected and that measures be adopted for farming this Establishment the least possible delay[115].

The decision was acted upon immediately because of increasing American settlement in the West threatened the British claim to the Northwest coast. James Douglas, a prominent Hudson’s Bay Company employee, first made an exploratory trip to the southern tip of Vancouver Island, and then on March 14, 1843, he returned to the island to build a fort.

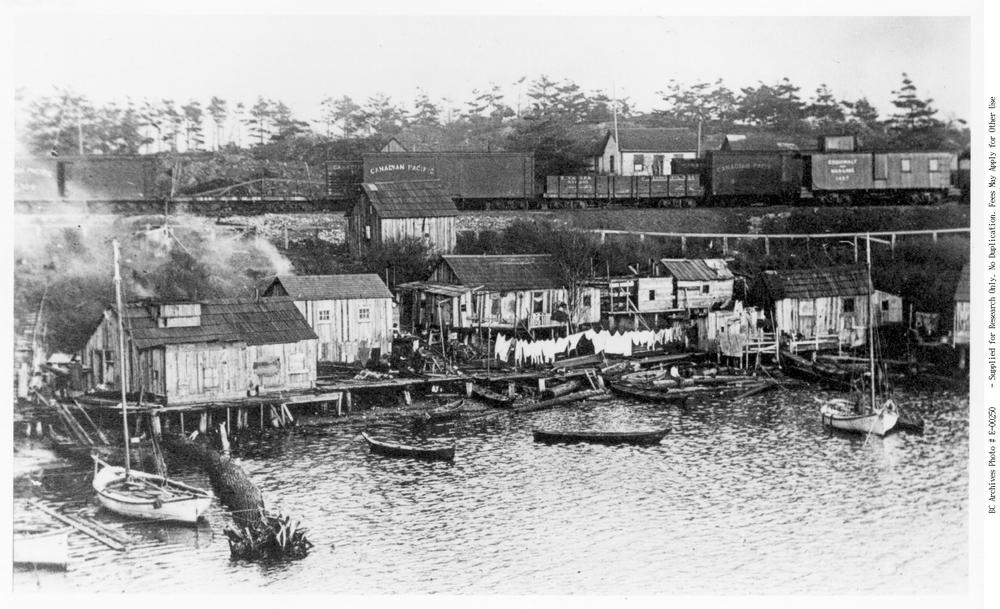

When the Fort’s construction began, the Songhees moved to its northern perimeter[116]. The Songhees Amalgamated at the site to the north of the Fort were called the “Swengwhung[117].” This was also the name given to the family who inhabited the area west of the Inner Harbor where Victoria now exists. The Teechaitsa, Whyomilth, Kosapson , Chilcowitch, Chekonein, and the South Saanich groups joined the Swenghwung at this location[118]. The villages abandoned by these groups were: Stangel, StchilKW, the site a Gorge Park, Ross Bay, Gonzales Bay, McNeil Bay, Oak Bay, Cadboro bay, Discovery Island, and Cordova Bay. There might have been Songhees who emigrated from Whitty’s Beach and Henry and San Juan Islands[119]. If the Village site existed on James Bay as Hill-Tout suggested in some Songhees might’ve joined the Kosapsom group at Shosappsom, the Legislative Buildings site[120].

The new village was perhaps the largest Songhees amalgamation, and it presented new social ramifications. For instance, at the Swenghwung Village, the lowest ranking Teechamitsa family from the southern part of Songhees territory, and the highest-ranking groups from Cadboro bay, were now living at the same site[121].

The implications of moving from the winter villages were probably not apparent to the Songhees.The abandonment of these village sites might be viewed by Europeans as a voluntary relinquishment of these territories, as the Songhees did not return to their previous billet sites. Songhees might not necessarily have assumed this on the basis of their own notions of land use and ownership. For instance, some groups had amalgamated at Cadboro Bay, and at the same time they shared the surrounding territory. The amalgamation did not signal diminished access to the abandoned territory or its resources[122]. Similar assumptions prevailed at the time of contact. From the new Swenghwung Village, the Songhees retained access to their food sites, and they continued their migrations to their reef net locations. The new village location also facilitated access to the Gorge, the Songhees’ most popular summer locale.

While the Songhees might not have welcomed the Europeans in their territory, they did not attempt to deny them access through armed resistance[123].

The Songhees were probably aware of the benefits that might emanate from the existence of the Fort in their territory. From the village adjacent to the Fort, the Songhees planned to control trade. They intended to be the “home guards”, as the Tsimishian had done at Fort Simpson. Like the Tsimishian, the Songhees gathered at the Fort’s walls and attempted to act as middlemen between the Indians and the company traders. On one occasion, after Indians from Bellingham Bay completed a trading transaction at the Fort, the Songhees robbed them of all their goods. Upon receiving complaints from the Bellingham Bay Indians, the Chief Factor, Roderick Finlayson, through the threat of reprisals, recouped their supplies and provided an escort to safe waters. It appears that the Songhees’ attempt to monitor Indian trading was curtailed by Finlayson’s heavy-handed approach.

Though the Songhees were required to conform to the demands of the Chief Factor by the threat of physical violence, there was some reciprocity in the Songhees relationship with the Hudson’s Bay company traders. The British possessed arms and these served to protect the Songhees. The Songhees located their original village on the northern edge of the Fort, where the building protected them from hostile groups entering the harbour. The Songhees, like other Straits Salish, had suffered great losses at the hands of the Yukulta, a southern group of Kwakuitl, who possessed muskets from 1792[124]. The Yukulta “killed, looted, and carried off women and children as slaves,” throughout the Coast Salish and Straits Salish territory[125]. The need for a defensible site was therefore an important factor in determining the location of a village[126].

At the new Swengwhung village site, there were numerous opportunities for employment. During the fort’s construction the Songhees exchanged pickets for blankets. Evidently the trees nearest the fort were not straight enough for building barricades. The Songhees were commissioned to find suitable trees. From as far away as five miles, these Indians hauled pickets measuring twenty-two feet in length by three feet in circumference. In return for forty pickets, the Songhees received on blanket[127]. The Songhees also assisted in the Hudson’s Bay Company’s agricultural activities. They ploughed fields[128] and planted potatoes[129]. The Songhees supplied the Fort’s residents with salmon and buckets of clams. Songhees men acted as guides and the delivered the fort’s mail by canoe[130].

The presence of the fort, and the subsequent Songhees participation in the labour economy, precipitated changes in the Songhees relationship with their environment. For instance, the Songhees involvement in supplying the fort’s pickets affected other aspects of their lives. This employment meant less time was available for previous forms of resource exploitation. The exchange of Songhees labour for goods, particularly blankets, affected their once necessary migrations to gather reeds for textiles. Changes to their migrations altered the social and religious activities associated with some of these subsistence activities[131].

The new wealth available through the wage economy influenced individual and group status. An individual displaying wealth accumulated through labouring at the fort could enhance both his families rank which was traditionally based on ascriptive or inherited rights, acquired power enhanced status and altered inter-group relations.

Although the presence of the fort caused changes in the Songhees relationship with the environment and their culture, they adapted to the European presence in their territory. Their initial response was accommodative, although, as settlement increased and the colonial government became increasingly dominant, the Songhees altered their position. Am examination of land negotiations indicates both the Songhees attempt to accommodate the European presence and the beginnings of the strained relations between the two groups.

Shortly after the construction of the Fort, Chief Factor Roderick Finlayson negotiated the first relocation of the Swengwhung Songhees. Because their village was seen as a fire hazard for the fort, Finlayson insisted that the Songhees move across the harbour[132]. He reported:

.. I wanted them to remove to the other side of the harbour which they first declined to do, saying the land was theirs and after a great deal of angry parlaying on both sides, it was agreed that if I allowed our men to assist them to remove, they would go, to which I consented[133].

The Songhees understood their rights to the land, especially to the site chosen on the inner side of the fort. Finlayson realized the motive for their refusal to relocate, yet he required that the Songhees move.

The Songhees fear of British reprisals might have contributed to their accommodative stance. On a previous occasion, when the Songhees refused to cooperate with Finlayson, he responded with a violent show of force. A Chief’s house was destroyed when a stolen oxen was not returned. Attempting to avoid such a confrontation, the Songhees agreed to a peaceful resolution of this first relocation issue, and they moved to the other side of the harbour[134].

There is some discrepancy regarding the site of the first relocated Songhees village[135]. “Across the harbour,” as described by Finlayson could have referred to a relocation to the site across James Bay, or it could have meant across the harbour where the Songhees eventually resided until 1910. Both might even have occurred. Some of the Swengwhung could have joined the Songhees at the Legislative Buildings site, and some others might have moved across Victoria Harbour[136]. This site, inhabited by the Songhees until 1910, was rocky with a poor water supply[137]. The Legislative Assembly Buildings site might have been a village, as this land was allotted as such, after the Songhees signed purchase agreements in 1850. Neither of these locations were as convenient as the Swengwhung site for the Songhees employed at the fort, a both were less easily defended. These disadvantages might explain the Songhees initial resistance to move.

The most significant land transaction involving Songhees territory occurred in 1850. In this year Chief Factor James Douglas signed a series of treaties with the Songhees and fourteen other Indian groups on Vancouver Island[138]. The territory of the Songhees was included in at least six of the treaties[139]. On April 29, 1850, the lands of the Teechamitsa, Kosampson, Swengwhung, Chilcowitch, Whyomilth, and Chekonein “became the entire property of the white people forever[140].” Two years later, treaties were signed with the North and South Saanich, some of which were known to be Songhees[141]. These deeds of conveyance, as Douglas called them, dd allow for the Songhees to retain their villages, potato patches and graveyards and provided for hunting on “ the unoccupied lands[142].”

On first glance, the treaties appear to recognize the Songhees aboriginal title. However, Douglas’s representation of Songhees land ownership was incorrect. As noted in chapter one, the Songhees shared most of their territory, while families claimed winter sites and individuals owned resource sites. While the treaties protected the Songhees village sites, by 1850, there were only two left. The treaties also guaranteed Songhees fishing and hunting. For the Songhees this meant that reefnet sites and other resource sites were guaranteed. However, this provision applied only as long as these places were not inhabited by Europeans[143]. Considering Douglas’ experience in dealing with Indians, it is debatable whether he recognized the limitations of the treaties, or what the future ramifications of the treaties might be.

When the treaties were signed, they represented a relatively good business transaction for the Songhees. They received payment for agreeing to conditions which already existed. The Songhees received blankets for living in allotted village site which they already inhabited, and for sharing their territories, which they had always done. Since the Songhees had already shared most of their lands, this was not a major concession on their part. Further, all they required was access to their food sites and hunting areas, both of which were guaranteed in the treaties. The Songhees probably did not comprehend Douglas’ motivation in signing the treaties. He wanted to free the land to allow for settlement in the vicinity of the fort.

When the treaties were signed, they represented a relatively good business transaction for the Songhees. They received payment for agreeing to conditions which already existed. The Songhees received blankets for living in allotted village site which they already inhabited, and for sharing their territories, which they had always done. Since the Songhees had already shared most of their lands, this was not a major concession on their part. Further, all they required was access to their food sites and hunting areas, both of which were guaranteed in the treaties. The Songhees probably did not comprehend Douglas’ motivation in signing the treaties. He wanted to free the land to allow for settlement in the vicinity of the fort.

Interest in the Songhees land ebbed until the discovery of gold. In 1858 Fort Victoria was inundated with miners. Land speculators also visited the colony during the gold rush and land values soared. The economic activity of the post in 1858 period at the fort, was accompanied by a concerted effort to remove the Songhees Indians from their reserve. Situated across the harbour from the fort, the Songhees land became extremely valuable. As well as impeding the development of the port, the was considered a safety and health hazard. The large gathering of Indians also offended the sensibilities of those attempting to build a “Little England” on the north west coast[144].

In the midst of the gold rush many persons approached the Songhees to purchase the ideally located land[145]. Douglas immediately took action and announced in the Victoria Gazette that title to the reserve was vested in the Crown, and that it was illegal for the Songhees to sell the land. However, Douglas was pressed by J.S. Helmcken and James Yates, members of the Legislative Assembly, to investigate the possibility of moving the Indians and selling their land[146]. Douglas responded that it would be neither “just nor politic” to remove the Indians, as the government was “bound by the faith of a solemn engagement to protect them in their enjoyment of their agrarian rights[147],” Ironically, prior to this statement, Douglas himself had contradicted its very premise. In the mid-1850s, the Songhees offered to sell the Skosappson reserve. Initially Douglas refused the offer, but soon after he accepted and the Songhees moved across the harbour. The James Bay site became the location of the Legislative Buildings and Douglas’s residence.

When Douglas negotiated the James Bay sale, he also arranged a leasing program on the new reserve[148]. Although Douglas had allowed some rental of this reserve, it was not until 1859, that he formally announced a leasing program in the House of Assembly[149]. The Songhees were given “trifling presents”[150] for the sale and use of their land, but it is likely Douglas promised a substantial revenue through the leases and the sale of the Skossapsom reserve. Later documentation of Band meetings shows that on several occasions elders stated that they never received the monies promised to them for the sale and leasing of their lands[151].

Though Douglas attempted to organize the leasing program on the Songhees reserve, his plan met with numerous obstacles. In 1862, he appointed a Board commissioned with the “management of the leasing on the reserve and the leasing account[152].” The members of the Board were J.D. Pemberton, the Surveyor general of the colony, A.W. Pemberton, a Stipendiary Magistrate, and E.G. Alston, the Registrar General of the Colony. One of Douglas’ previous leasing assistants W.A.G. Young, the Colonial Secretary, continued to assist the commission. J.J. Cochrane and later L. Lowenberg acted as land agent and treasurer[153].

The efforts of the commission were sporadic and unorganized due to the prolonged absence in England of A.F. Pemberton and the lengthy illness of J.D. Pemberton[154]. A fiscal statement prepared in 1864, at the request of Governor Kennedy, showed that two-thirds of the reserve land had been leased and that the total annual rent should have been $1404.00[155]. The irregularities of the commission meant that rents were not always collected, nor were they regularly disbursed to the Songhees[156].

The first record of disbursement occurred in 1860 when the Indian Improvement Committee requested and was granted funds and a site for a schoolhouse on the Songhees reserve[157]. In 1861 missionary A.C. Garrett submitted a second plan for the “Administration of a portion of the funds accruing from the Indian Reserve[158]” and he requested $142.00. in 1862 he asked for a further $248.00 to purchase food and clothing for the Songhees[159]. When petitioning the Colonial Secretary to approve his request, Garrett drew attention to the Songhees dissatisfaction with the leasing program. He stated that “the Songhees Indians have now for a long period been watching with a jealous eye the occupation of their reserve by the whites. They have consented to this occupation because they have been repeatedly informed by authority that funds would be obtained to be devoted to their own benefit[160].” The rents did not amount to much for the Songhees. As a result of irregularities in the leasing program, only $1078.00 was collected between 1860 and 1863[161]. The Songhees received less than half of the money collected. In 1865, Governor Kennedy declared the leases illegal and forbade the collection of their rents[162]. Two thirds of the reserve had been leased to whites and the Songhees received a very small percentage of the payment.

In 1869 the leasing fiasco was handed over to Joseph Trutch, the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works, who in turn, wrote to the Colonial Secretary in London suggesting a course of action[163]. Trutch proposed that because no formal writ had been issued after Kennedy’s declaration, that each of the leases be ordered to pay back rents within thirty days. Those paying could retain leases while those not paying would forfeit their lease[164]. Most leaseholders chose not to update their lease as the site had become undesirable to reside upon. Further, because resale was impossible, the land was worthless for speculation[165]. Only three leases continued until the reserve was surrendered[166].

In 1871, when British Columbia entered Confederation, the provincial treasury passed the $1984.82 that accrued from the leases to the Dominion government as a “general” surplus. The provincial government ignored the fact that the source of he funds was the Songhees leases and that the Songhees were the rightful recipients, but the Songhees did not[167]. The money the government owed the Songhees became a thorn in the side of both the federal and the provincial governments.

Throughout the contact and settlement period, the Songhees accommodated and resisted European pressure for their land. The Songhees accommodated the initial European demands for the relocation of their village and the European use of their territory. Throughout these interactions they also attempted to fulfill their own needs. The existence of the fort in their territory gave the Songhees new and useful resources. It brought wealth and prestige both to individuals and the Songhees groups. The Songhees worked as labourers at the fort to acquire new wealth. While changes in the Songhees economy altered their relationship with the environment, the Songhees were amenable to the European presence.

The Songhees agreed to Finlayson’s relocation and to Douglas’s treaty arrangements. The Songhees also accepted Douglas’ promised revenue for the sale and leasing of their lands. While the Songhees might not have understood the notions of ownership contained in the treaties, they were willing to share their territory, to foster peaceful relations and to maintain the advantages to their economy.

During the gold rush, the Songhees territories became densely populated and limited access to their resources became an imminent reality. They learned that the treaties did not guarantee unoccupied lands for hunting and fishing. These circumstances contributed to the development of strained relations between the Songhees and Europeans, especially regarding land when injustice resulting from the land deals became evident, the seeds of the Songhees resistance were sown, and their intransigence regarding relocation was to frustrate federal and provincial governments for the following forty years.

Chapter Three

The Federal-Provincial Debate on the Terms for the Songhees Relocation – 1871-1911

After British Columbia joined Confederation, Indian Affairs became a federal responsibility. The Songhees Indians along with all Indians in the province became wards of the dominion government. Attempts to relocate the Songhees Indian reserve lead to a jurisdictional dispute between the federal and provincial governments regarding title to the Songhees reserve. The case of the Songhees reserve was just one of the numerous battle grounds in the federal provincial war over Indian land in British Columbia. An examination of the protracted debate between the governments is necessary in order to understand the Songhees resistance.

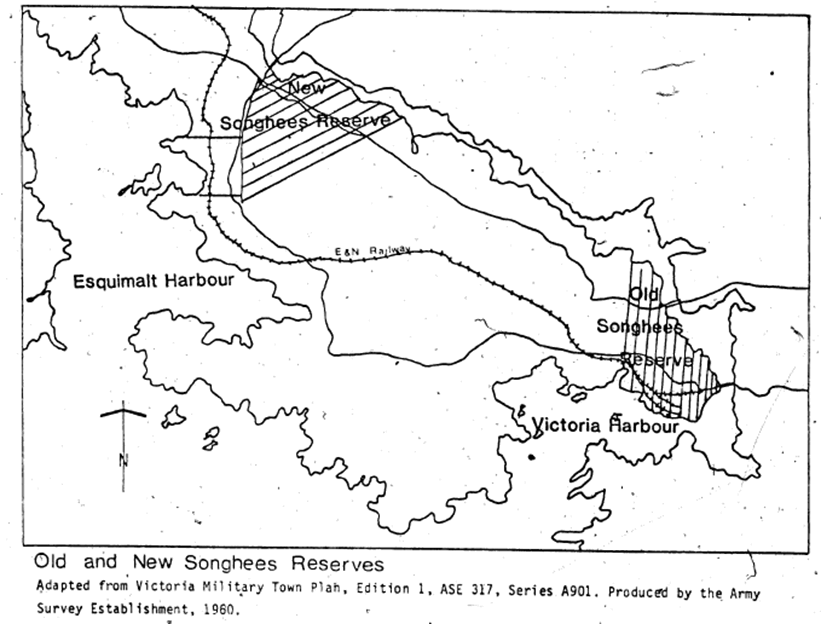

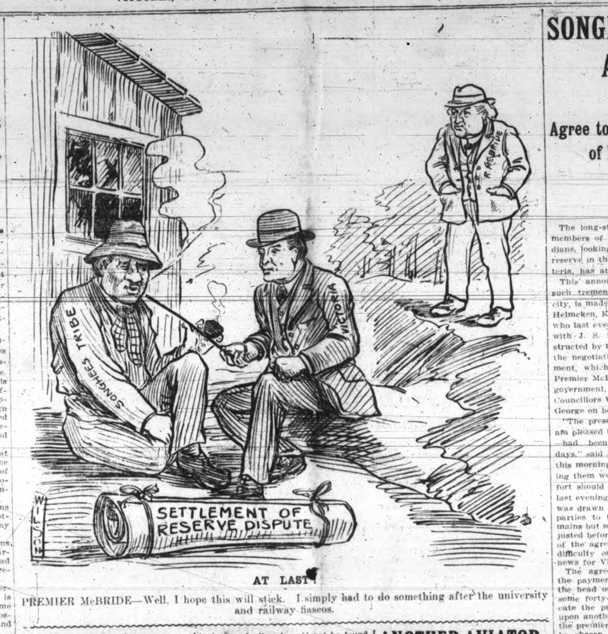

Despite repeated challenges from the province, the federal government maintained that title to the Songhees reserve belonged to the dominion. Department of Indian Affairs officials also insisted on a free hand to negotiate the Songhees relocation. The federal government stood firm despite the provincial government’s insistence on the Songhees removal, and on its reversionary claim to the reserve’s title. The impasse between the governments regarding the Songhees reserve was finally resolved in 1911. The terms agreed to represent a compromise in which each government moved from its original position. The government’s compromise coincided with a Songhees agreement to surrender the reserve, thus concluding the longstanding Songhees reserve question.

From 1871 until 1895, interest in the relocation of the Songhees removal stemmed primarily from a concern for the negative effect the city had on them. Liquor and prostitution combined with numerous occurrences of violence were cited as reasons why the Songhees should be moved[168]. The relocation of the Songhees was also considered desirable because of the barren terrain of the city reserve[169]. The Superintendent of Indian Affairs for British Columbia, F.W. Powell, noted that the Songhees reserve was rocky and lacked water. He proposed a move to a more arable tract of land. Powell believed that an agriculturally based economy would improve the quality of the Songhees lives[170]. Powell proposed various alternate sites, but the Songhees were not interested in moving[171].

The only relocation attempts which nearly succeeded occurred in 1880. Joseph Trutch, acting as Dominion Agent in British Columbia on railway matters, and probably wanting the land for related purposes , requested the Songhees removal. Trutch gathered the signatures of those Songhees willing to move to Cadboro Bay[172]. Some Songhees were wiling to return to their traditional village site, but the majority of the Songhees refused to move and the Band remained on the city reserve[173].

As the population of he capital city grew and demands on the port facility increased, requests for the Songhees removal became more vociferous and frequent[174]. In 1891 the city through the Lieutenant Governor, petitioned the federal government for a relocation agreement. The Department of Indian Affairs responded positively to the request. The reserve was evaluated, and a proposed agreement was drawn up[175]. The Department also solicited the Songhees for their opinion regarding the suggested relocation. When the Songhees were unavailable for negotiations because they were away picking hops, the negotiations collapsed[176].

In 1895 the province once again took the initiative. Spurred by numerous inquiries in the Legislative Assembly regarding the status of the reserve, the Executive Council of British Columbia presented a report to T. Mayne Daly, Superintendent of Indian Affairs[177]. The Council proposed a plan to move the Songhees “from the temptations and demoralizing influences of a large city to a more appropriate location, and at the same time to place the land upon which they now reside at the disposal of the provincial government in order it may be more suitably occupied[178].” Also, terms were recommended for the settlement of he Songhees question. The Council’s report was seminal for it explained the province’s claim to the title of the Songhees reserve and, at the same time, offered a rationale for a claim of reversionary title to all reserves in the province.

According to the report, reversionary title was vested in the province on the basis of certain points of law. The Songhees were excluded from holding title to the reserve as the Kosampsom treaty which this family signed in 1850, did not allot the “fee simple” to them, but merely “reserved” this site for their use[179]. The report argued that Article Thirteen of the Terms of Union which stated that. “The trustee and management of the lands reserved for their use and benefit shall be assumed by the dominion government.”, did not grant the dominion to any right of title[180]. While clause thirteen emphasized the role of the federal government as trustee of the Indians, title to the reserves was not allotted, but rather the reserves set aside for Indians were for their “use” only as long as they needed or populated the land. It was argued that lands not being “used” by Indians then reverted to the province. This reversionary right was guaranteed, the report claimed, in the terms of the 1876 Joint Commission on Indian land, when the two governments, in an attempt to determine the size and location, agreed that reserves no longer in use by Indians reverted to the province. A third argument for provincial claim to reserve title was the assertion that subsection five of section twenty-nine of the British North America Act assigned to the provinces the management and sale of public land belonging to the province. According to the Executive Council’s report, the title to the Songhees reserve was vested in the province by the Crown and held in trust for the use of the Songhees by the dominion. The report stated that if the dominion government released its right to manage the reserve, then the province could act to solve the location problem “to the satisfaction of all parties[181].”

The report concluded with suggested terms to be offered the Songhees, including their relocation on approximately 950 acres, with some waterfrontage, in Metchosin. This land was to be given “in trust” to the Songhees and title to the new reserve was to be retained by the province. The report suggested that compensation be paid for improvements and rents collected for the leases be applied to the purchase of livestock, implements and a new school. The terms made provision for the Songhees who were steadily employed in the city. Lots would be purchased at Rock Bay, so these Indians could build new homes close to their work[182].

The Executive Councils’ comprehensive terms were designed to satisfy the Songhees and to secure a provincial claim to the title to their reserve. The report placed the Songhees reserve question within the framework of British Columbia’s reversionary claim to all Indian reserves in the province. By denying that the Kosampsom treaty extinguished aboriginal title to the area, the province was able to consider the Songhees reserve in the same class as other reserves. The reversionary claim was a stumbling block for both of the governments, but especially the federal government. The province’s claim to reversionary title impeded the dominion’s ability to manage the reserves in British Columbia. If he province acquired title to the reserve when the land was no longer used by Indians, then the federal government was blocked from accruing funds through leasing programs. As long as both governments claimed title neither could gain access to the Indian land. While the province was reluctant to grant lands to Indians it was quick to reclaim unused lands. The provinces’ obdurate attitude regarding Indians was an impediment to a satisfactory solution to the Indian land question.

The Report of the Executive Council Embodied a claim which favoured he province rather than the federal government regarding Indian reserve ownership. The federal government, as trustee, assumed conversely that it held title to the land for the benefit of the Indians. The disagreement over Indian land was one aspect of the ongoing disagreement between the province and the dominion, regarding the interpretation of the jurisdiction of powers as set out in the British North America Act and the Terms of Union[183].

After receiving the Executive Council’s report, the Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Hayter Reed, requested legal advice[184]. T. Bray, a lawyer acting on behalf of the federal government submitted an opinion which contradicted the position taken by the British Columbia Executive Council[185]. According to Bray, the dominion rather than the province retained title to the Songhees reserve. Bray argued that Indian reserves in British Columbia had been set aside for Indian’s use in different ways and that reserves could be classified according to the particular method by which the land was allotted. Bray classified the Songhees reserve along with all other reserves allotted through treaties[186]. He argued that the Songhees reserve was in a special class because of the treaty these Indians had signed through James Douglas and the Hudson’s Bay Company. He supported this position with the evidence that the Joint Commission on Indian Lands in British Columbia also submitted that the Songhees Indian reserve was in a special class over which the Commission had no jurisdiction[187]. When reporting to Daly, Hayter Reed misjudged the province’s interpretation of the issues at stake, and thought that, if it acted at this time, the dominion government could solve the problem of reversionary rights once and for all[188].

Daly did not take Reed’s advice but suggested that action on the Songhees question be postponed until the Supreme court had ruled on the Naniamo Indian reserve case[189]. In this case, the federal government was challenged by the province regarding the right to lease a section of the Naniamo reserve for coal mining. The British Columbia government based its challenge on Section 13 of the Term of Union. The province held that if the Indians were not using the land then it became the property of the people of British Columbia. The federal government, which considered itself to be the trustee of the Indians, believed it was acting in this capacity, when administrating reserve lands. The Department of Indian Affairs held that leasing sections of the reserve was part of their administrative responsibilities. Following Daly’s recommendation, further action on the Songhees reserve question was postponed[190].

After a year, the British Columbia government tried once again to solve the Songhees reserve question. The Executive Council recommended the formation of a “special commission”[191]. Daly agreed on the condition that the agreement not prejudice the dominion government’s claim to other reserves in the province and that the title of the yet to be determined Songhees reserve be conveyed to the dominion as “trustee of the Indians”[192]. Peter O’Reilly was appointed as the federal government’s representative on the commission[193]. The provincial government appointed Dennis Reginald Harris, a lawyer who practiced in Victoria. To speed up the settlement, the province agreed to convey the title to the new Songhees reserve to the dominion. The provincial government maintained its claim to the reversionary rights to the city reserve and agreed that the settlement would not prejudice the future status of reserves in British Columbia. This deal embodied compromise by both governments but the federal government remained hesitant[194].

Soon after his appointment in 1896, Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Hugh Macdonald[195], reported to the Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia, E, Dewdney that the Commission’s terms regarding title were deficient. He pointed out that the existing reserve’s real estate value was greater than that of the proposed new reserve. On the basis of this observation Macdonald suggested that the commission decide upon a just compensation for the dominion. He also requested compensation for the Songhees for improvements to their land[196].

The federal government had pushed the province too far. Clerk to the Executive Council, James Baker informed the new Prime Minister, Wilfred Laurier that, if “the British Columbia government was required to pay a cash indemnity in addition to the land, there would be an end to the matter”[197]. Newly appointed Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, Clifford Sifton, advised the Deputy Minister, Reed, to stall this issue and that of the revision of all Indian reserves in British Columbia. Sifton also asked Reed if the Songhees had agreed to the move[198]. Reed informed Sifton that, “The question of removal has not yet been formally submitted to the Songhees[199].” While the governments were debating the committee’s objectives neither party had consulted the Indians themselves. The Songhees were not asked whether they would withdraw their opposition expressed a year and a half earlier.

In February 1897 Sifton restated the federal government’s position regarding the terms of the proposed commission[200]. The provincial government refused again to pay compensation to the dominion and the Songhees. While British Columbia had agreed to compensate the Songhees for improvements on the old reserve in 1895, it continued to refuse a supplementary payment to the federal government. Baker explained that the provincial government believed that the reserve’s real estate value was “ancillary to the transaction of he relocation of the Indians”[201]. He stated that “the value of the present Songhees Reserve has been created by causes entirely independent of the said Indians and in spite of their customs, habits and avocations”[202]. Baker did not recommend that the commission proceed with the question of the Songhees reserve on the basis of the government’s limited agreement.

In an attempt to solve the impasse Sifton and Premier Turner appointed J.A.J. McKenna to negotiate with a representative of the British Columbia Government, regarding the scope of the ill-fated commission[203]. McKenna made several proposals but failed to gain an accord between the two governments.[204]