The War Scare of 1854

Donald C. Davidson

BC Historical Quarterly October 1941.

THE WAR SCARE OF 1854. THE PACIFIC COAST AND THE CRIMEAN WAR.

The Crimean War grew out of the hostilities which commenced between Russia and Turkey in October 1853. From the first it was evident that Great Britain and France might join in the conflict, and within a few months they were preparing to intervene on the side of Turkey. Under these circumstances the British Colonial Office judged it prudent to sound an alert for the benefit of the colonies. It took the form of a circular dispatch, dated February 23, 1854, which warned that Great Britain and France were preparing for all contingencies, and which instructed the British officials throughout the world to act in conformity with the alliance of the two countries by giving protection to French subjects and interests, equal to that given to British interests.[1]

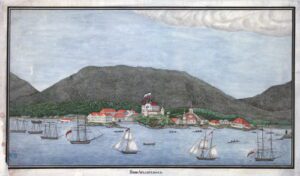

It was the middle of May before this dispatch reached James Douglas, Governor of the remote colony of Vancouver Island. On March 28, fully six weeks before its arrival, Great Britain had declared war; but this was not known in Vancouver Island until June, and the Governor did not receive an official notification until as late as July 16.[2] Stranger still, Douglas was left for some months in complete ignorance of the fact that an exchange of letters between the Russian American Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company[3] had resulted in an agreement between Russia and Great Britain which, for practical purposes, made the whole eastern Pacific a neutral zone. Once this agreement was concluded, the British Government naturally looked upon the defence of Vancouver Island as a simple matter and considered that the occasional visit of a British warship would suffice. But the Government and colonists in Vancouver Island, who knew nothing of its existence, naturally worried about a possible attack from Russian America, and took steps to meet it. Nor should the fact that the threat to the colony was never great, except in the minds of the residents of Victoria, be permitted to obscure the fact that their activities were sincere demonstrations of a desire to do their utmost both for local defence and for the prosecution of the war in its larger aspects.

The circular of February 23, 1854 was accompanied by a dispatch in which Douglas was instructed to report any measures which he might have taken to protect British and French interests and toward co-operation with the British Navy.[4] The Governor replied to these instructions on May 16, three days after he received them. Having punctiliously acknowledged the part of the dispatches which had little application to Vancouver Island by stating that he would protect French interests, Douglas passed on to the much more important question of local defence. Since the Island was without military protection, he felt that an irregular force of whites and Indians should be raised in anticipation of possible attack. He pointed out that he had no authority to raise such a force and recommended that he be so empowered. He enclosed a requisition covering the estimated costs, including those of storehouses, barracks, arming, equipping, and maintaining. In addition to this levy of men, Douglas assumed that additional protection would be afforded by a detachment of the fleet which would be stationed at Vancouver Island. He also suggested the advisability of considering an attack on Russian America, which, he considered, could be taken by a force of 500 regular troops. This action would preclude the use of Russian American ports as privateering bases and would deprive Russia of her possessions and fur trade in America.[5]

These tentative proposals of the Governor took into consideration the three factors which were important to the colony’s defence as he saw the problem at the time. These were local protection against invasion by land, maritime defence against privateers and enemy vessels, and possible aggressive measures against Russian America.

Unofficial news of the declaration of war reached Victoria in the middle of June, and Douglas wrote to the Hudson’s Bay Company expressing surprise that nothing had been done to protect the colony, either by sea or by land.[6] The minutes of the Council of Vancouver Island for July 12, 1854, record that consideration was given to Douglas’s proposal to draft all the men in the colony capable of bearing arms, and to supplement this group with armed Indians. Douglas found that the Council opposed his plan; it was felt that the number of white men in the colony was too few to offer effective resistance against an attack, and that it was even more dangerous to arm the Indians who might turn against the white men. It was therefore decided not to call out the militia, and to leave the defence of the colony to the British Government.[7] Her Majesty’s Government, according to a dispatch to Douglas dated August 5, thought that it would be “both unnecessary and unadvisable” to give the Governor powers to spend money on a military force, in view of the directions which had been given by the Admiralty for ships of war to visit the colony.[8] The Hudson’s Bay Company had previously suggested that the presence of one or two ships in the locality of Vancouver Island would be adequate for the protection of “our” servants and colonists, and concurred in the opinion that an armed force was unnecessary, except in so far as it might serve as protection against local Indian tribes,[9] in which latter case, the Company, by its charter, would probably have been required to pay the expenses. As a consequence, Douglas was not empowered to raise an armed force, but he continued to hold the opinion that some armed force should be at his disposal.[10]

The one positive action taken in the colony for its defence was the chartering of the Hudson’s Bay Company steamer Otter, a move which was approved by the Council at the same meeting at which it decided against calling out the militia. The vessel and her crew of thirty were to be employed as an armed guardship until London took other measures for the protection of the colony.[11] Thus, at an estimated cost of about £600 per month, an attempt was made to alleviate the fear of attack in Victoria, particularly by privateers. It was assumed that the costs would be paid by the Imperial treasury,[12] but, since the action was taken on local responsibility, the Governor later had great difficulty in justifying and securing payment for the £400 which was incurred for the short period during which the Otter acted as patrol. On December 18, 1854, Sir George Grey wrote that the Government could not hold itself responsible for that charge and regretted that Douglas had not waited for instructions before taking action.[13] The Government was ultimately persuaded to reconsider the matter, as the Hudson’s Bay Company would have had to bear the expenses incurred by the colony. In August 1855, Douglas was finally informed that the costs would be borne by the Government,[14] and in December of that year he sent his accounts for the £400.[15]

With modern communication facilities the colony would long since have been relieved of its feelings of concern. Had Douglas been aware of the correspondence which took place between the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Russian American Company during the earliest months of the war he could have reassured the residents of Victoria, and would not have been embarrassed by the measures of protection which he took on his personal responsibility.

In the middle of February, some weeks before Great Britain entered the war, the Russian American Company had obtained Imperial approval of a plan to write the Hudson’s Bay Company suggesting that efforts be made to have the territories of the two companies declared neutral. The Russian company had told its Government that this matter had been tentatively discussed at the time of the lease of the lisière to the Hudson’s Bay Company and that the latter had approved, idea in principle.[16]. Soon thereafter a letter was on its way to the London reminding the Hudson’s Bay Company that Sir George Simpson in 1839 had been of the opinion that it would be to the mutual interest of the two companies to have their territories declared neutral in case of war. The Russian company was able to state that it could secure official approval, if the Hudson’s Bay Company could secure the consent of the British Government to such a declaration.[17]

The matter had been simple to arrange in St. Petersburg and was to be almost as easy in London. The Governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company sent a copy of the Russian letter to his Government on February 28, covered by a letter which emphasized the defenceless state of the area involved.[18] On March 22, Her Majesty’s Government informed the company that it was willing to agree to a statement of neutrality for the territories of the two companies, but reserved the right to seize all Russian vessels and to blockade any Russian port.[19] These reservations were never of significance, but the Russian American Company promptly made arrangements to have all its vessels fly neutral flags and to increase trade with California.[20] In the middle of May arrangements for neutrality were complete and acknowledged by both sides.[21] The Russian fleet had been informed of the agreement,[22] and previous orders to the British fleet[23] on the subject were soon confirmed.[24]

Technically, Vancouver Island, as a colony, was perhaps subject to attack by Russia. While the Government in St. Peters burg may have realized this, its official attitude was conditioned by the attitude and position of the Russian American Company. That organization had a complete monopoly of all phases of Russian activity in America. The Hudson’s Bay Company had previously occupied a similar position, and a dual relationship continued in the new colony of Vancouver’s Island. No Russian attack on the colony would have failed to harm the Hudson’s Bay Company. It is doubtful if the northeastern Pacific was given much serious consideration in either London or St. Petersburg, except by officials of the companies.

Douglas reported that the colony was in “a state of perfect tranquility” in December 1854, there being no rumours of attack from the enemy.[25] However, in acknowledging dispatches which disapproved of his somewhat ambitious plans of the previous summer, he became almost plaintive on the subject of his inability to allay the fears of the inhabitants by more concrete measures than passing on promises that the colony would be visited by ships of war. During 1854 only once had the colony been paid such a visit.[26]

The first year of the war saw the completion of the neutrality agreement and the clarification of the policy of defence of the area solely by the British fleet. The year 1855 found the colony acting in co-operation with the Pacific Squadron in several ways and collecting for the Patriotic Fund. The story of the colony’s co-operation with the squadron, while marked with traces of discouragement, is of historic interest because it tells of the beginnings of Esquimalt as a naval base. In February 1855, Rear-Admiral Henry W. Bruce, Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Station, wrote Governor Douglas from Valparaiso requesting that provisions, coal, and temporary hospital accommodation he made ready for a visit of the fleet in July. While the assembling of the supplies was a worry, the significance of this task was less than that laid before the colony in the request for a hospital.

One of the items required was 1,000 tons of coal. When he received the letter, Douglas was hopeful that this could be assembled by the time the fleet arrived. The meats he planned to secure from Fort Nisqually. Vegetables were difficult to procure, but Douglas hoped to secure these also.[27] Orders were sent to the superintendent of the coal-mines at Nanaimo for the coal; the agent of the Puget Sound Agricultural Company was instructed to forward 2,000 sheep and as much beef as possible, and the residents of the colony were informed of the coming visit of the fleet and encouraged to raise vegetables to fill the prospective demand. In addition, Douglas was of the opinion that the Admiral should appoint a commissary officer to remain in Victoria as agent for the purchase of foods from the colony and from the American settlements.[28] Since the colony could not produce enough, Douglas apparently had sent agents to Puget Sound to gather together live stock.[29] At the end of June Douglas himself went to Nanaimo in connection with the coal delivery, and reported that some 900 sheep and 40 head of cattle were in readiness for the fleet. [30] The supplying of the fleet was completed to the pride and satisfaction of Douglas.[31] The hospital was a more thorny problem. Douglas decided the scope of this project largely on his own responsibility and found his action difficult to justify, although less so than in the case of the chartering of the Otter.

The phrasing of Rear-Admiral Bruce’s request for temporary hospital accommodation was vague. Douglas was quick to detect that little was said on the subject of costs; indeed, he thought the Rear-Admiral evaded the issue.[32] Despite doubts that the colony might eventually have to pay for the buildings, he went ahead with plans. Having found that there was no suitable building available, the Governor and Council decided to erect several buildings at Esquimalt.[33]

Three buildings were completed by the end of June,[34] at an expense of £938/3/6.[35] The Governor, was firmly convinced that they were the most economically built structures in the colony.[36] Each of the interconnected buildings was 30 by 50 feet and had 12-foot ceilings and large windows. There was an operating room, a kitchen, an apartment for the surgeon, and two wards, capable of accommodating 100 patients.[37]

The hospital was adequate for an emergency greater than that created when the squadron visited the colony on its return from Petropaulovski in the fall of 1854. At that time those wounded at the siege of the Russian port were taken on to San Francisco.[38] In view of the fact that only one patient, an engineer very ill with scurvy,[39] occupied the hospital during the visit of the squadron in July, 1855, on its return from its second visit to Petropaulovski, the expense of almost £1,000 might well have seemed excessive to Rear-Admiral Bruce. He expressed surprise at the expense to which the colony had gone, and wondered if an existing building might not have been adapted for the purpose. Douglas replied with a long statement of his reasons for making a permanent investment in well and cheaply constructed buildings, in preference to modifying a structure which would have remained the property of the Puget Sound Agricultural Company.[40] The accounts, however, were not challenged by the Government in London.

“I think you would find it convenient to make this place a sick Depot, or what is better a general naval Depot for the Pacific Fleet.” So wrote Douglas. to Bruce in August 1855.[41] The erection of the hospital had a definite relation to this idea, for it marked the beginning of Esquimalt’s fifty-year history as a British naval base.

Although Vancouver Island was visited a number of times in 1855 by British warships, the base at Esquimalt was not of importance in the strategy of the war in the Pacific. It was a convenient supply-point and not much more. This limitation was a direct result of the neutrality agreement made between the fur-trading companies of the nations at war. Had the agreement not been consummated the course of northwestern American history might well have been altered. Russia would have had to defend Sitka and other American ports but would also have had bases for possible attacks on British Columbia.

It seems inconceivable that, at least, the import of the arrangement was not promptly communicated to Governor Douglas. Apparently, however, he received no official information on the subject until September 1855. This represented a delay of over a year, and is a possible clue to the amount of thought given to the colony during the war. If Douglas knew of the agreement before this time he did not feel free to transmit his information to the colonists or to mention it in his official dispatches. At long last, he was sent copies of official instructions to the Admiralty on the subject of respecting the neutrality of Russian American Company’s territory, and these provided him with the information by which he could allay the fears of the colonists.[42] The unusual nature of the agreement may have accounted for the secrecy observed; but, whatever the reason, the colony apparently remained in ignorance to a very late date, despite its close connection with the Hudson’s Bay Company and despite the visit of ships of the fleet in 1854. Both the company and officers of the fleet were, of course, well aware of the agreement by the fall of 1854.

At the beginning of the war several Russian warships were in the Pacific. As a result of the agreement these vessels were forced to depend for a base on Petropaulovski, on the eastern side of the Kamchatka peninsula. Accordingly, the naval strategy was confined to the northwestern part of the ocean, where the very weak Russian squadron made its base. An attack on Petropaulovski in the fall of 1854 was unsuccessful, perhaps because of the suicide of Rear-Admiral Price just before the attack started. When an augmented British and French squadron returned to the attack in May 1855, it found that the Russians. had slipped away, and was forced to content itself with the destruction of the fortifications.

Throughout the war the neutrality agreement was respected by both sides. On July 11, 1855, the Pacific squadron, on its return from Petropaulovski, approached Sitka. The Russians were alarmed and sent the Governor’s secretary and a translator out to meet H.M. screw sloop Brisk. Rear-Admiral Bruce asked questions concerning ships in Sitka harbour, and left a package of newspapers. The squadron left without entering the harbour.[43]

Vancouver Island came through the war unscathed. It had demonstrated its spirit of co-operation in a number of ways. It made what would seem to be an excellent showing in collecting contributions for war work. A Patriotic Fund had been established in Great Britain for the purpose of supporting the wives and families of members of the armed forces who fell in action. On receipt of instructions, Douglas promptly appointed a committee composed of Rev. Edward Cridge, the chaplain; Robert Barr, the master of the school; and James Yates, to organize the campaign.[44] This action was taken in May 1855, and four months later over £60 had been collected. This amount which seems large for a small settlement, was warmly acknowledged.[45] The same committee was appointed in 1856 to collect for the Nightingale Fund.[46] In general, the conduct of the new colony of Vancouver Island during the test of war was honourable. While there was fear, discouragement for the officials, and somewhat casual treatment by the Home Government, the colony showed its willingness to do its utmost in meeting the challenge.

DONALD C. DAVIDSON.

THE UNIVERSITY OF REDLANDS, REDLANDS, CALIFORNIA.

[1] Circular, February 23, 1854, signed Clarendon; MS., Archives of B.C.

[2] James Douglas to the Duke of Newcastle, July 20, 1854; MS., Archives of B.C.

[3] For a sketch of the growth of co-operation between the two companies, vide supra, pp. 33—51. British Columbia Historical Quarterly, Vol. V., No. 4.

[4] Newcastle to Douglas, February 24, 1845; MS., Archives of B.C.

[5] Douglas to Newcastle, May 16, 1854; MS., Archives of B.C.

[6] Douglas to the Governor and Committee of the Hudson’s Bay Company, June 15, 1854, extract enclosed in John Shepherd, Deputy Governor, to Frederick Peel, August 19, 1854. Transcript in Archives of B.C.

[7] Minutes of the Council of Vancouver Island (Archives of B.C., Memoir No. II.), Victoria, 1918, pp. 24—5.

[8] Sir George Grey to Douglas, August 5, 1854; MS., Archives of B.C.

[9] John Shepherd to Frederick Peel, August 19, 1854; MS., Archives of B.C.

[10] Douglas to Sir George Grey, February 1, 1855; MS., Archives of B.C.

[11] Minutes of the Council of Vancouver Island, be. cit.

[12] Douglas to Newcastle, August 17, 1854; MS., Archives of B.C.

[13] Grey to Douglas, December 18, 1854; MS., Archives of B.C.

[14] Sir William Molesworth to Douglas, August 3,1855; MS., Archives of B.C.

[15] Douglas to Molesworth, December 10, 1855; MS., Archives of B.C.

[16] Memorial of Count Nesselrode, January 23/February 4, 1854, Alaska Boundary Tribunal, Counter Case of the United States, Washington, D.C., 1903, Appendix, p. 14; cited hereafter as Counter Case of the United States, Appendix. Also issued as Proceedings of the Alaska Boundary Tribunal (U.S. Cong., Cong. 58, Sess. 2, S. E. 162), Washington, 1903—04, vol. IV.

[17] Major-General V. Politkovsky, Chairman, Board of Directors, Russian American Company, to Directors of Hudson’s Bay Company, February 2/14, 1854. Transcript in Archives of B.C.

[18] A. Colvile to the Earl of Clarendon, February 28, 1854. Transcript in Archives of B.C.

[19] H. U. Addington to Hudson’s Bay Company, March 22, 1854, Counter Case of the United States, Appendix, p. 18.

[20] Board of Directors, Russian American Company, to Chief Manager of Colonies, April 16/28, 1854, ibid., pp. 16—17.

[21] John Shepherd to Russian American Company, May 16, 1854, ibid., p. 18.

[22] Minister of Finance to Admiral of Fleet, April 8/20, 1854, ibid., pp. 15—16.

[23] Lord Clarendon to the Admiralty, March 22, 1854; MS., Archives of B.C.

[24] R. Osborne to Rear-Admiral David Price, May 4, 1854; M.S., Archives of B.C.

[25] Douglas to Archibald Barclay, December 20, 1854; MS., Archives of B.C.

[26] Douglas to Grey, February 1, 1855; MS., Archives of B.C.

[27] Douglas to Barclay, April 25, 1855; MS., Archives of B.C.

[28] Douglas to Rear-Admiral Bruce, May 8, 1855; MS., Archives of B.C.

[29] Douglas to the Colonial Secretary, June 13, 1855; MS., Archives of B.C.

[30] Douglas to Bruce, June 28, 1855; MS., Archives of B.C.

[31] Douglas to William G. Smith, September 14, 1855; MS., Archives of B.C.

[32] Douglas to Barclay, April 25, 1855; MS., Archives of B.C.

[33] Douglas to Bruce, May 8, 1855; MS., Archives of B.C.

[34] Douglas to Bruce, June 28, 1855; MS., Archives of B.C.

[35] Douglas to Smith, September 14, 1855; MS., Archives of B.C.

[36] Ibid., September 21, 1855; MS., Archives of B.C.

[37] Ibid., October 10, 1855; MS., Archives of B.C.

[38] W. N. Sage, Sir James Douglas and British Columbia, Toronto, 1930, p. 182.

[39] Douglas to Smith, July 19, 1855; MS., Archives of B.C.

[40] Douglas to Bruce, October 25, 1855; MS., Archives of B.C.

[41] Ibid., August 3, 1855; MS., Archives of B.C.

[42] Lord John Russell to Douglas, June 20, 1855; Douglas to Russell, September 21, 1855; MSS., Archives of B.C.

[43] Report of the Board of Directors of the Russian American Company, November 16/28, 1855, Counter Case of the United States, Appendin, pp. 20—21. Douglas to Sir George Simpson, August 7, 1855; MS., Archives of B.C.

[44] Grey to Douglas, January 23, 1855; Douglas to Rev. Edward Cridge, May 16, 1855; MSS., Archives of B.C.

[45] Douglas to Cridge, September 7, 1855; H. Gardiner Fishbourne, Honourary Secretary, Royal Commission of the Patriotic Fund, to Douglas, December 10, 1855; MSS., Archives of B.C.

[46] Douglas to Cridge, May 19, 1856; MS., Archives of B.C.