RUMOURS OF CONFEDERATE PRIVATEERS OPERATING IN VICTORIA, VANCOUVER ISLAND

Benjamin F. Gilbert.

San Jose State College, San Jose, Calif.

The British Columbia Historical Quarterly, Vol XVIII, July-October 1954 pp239-255

The threat of privateering in the Pacific during the American Civil War presented a major problem to the United States State Department and to the Pacific Squadron of the navy. The Confederate States planned to interfere with California’s commerce and to capture gold shipments along the Pacific Sea lanes, for a stoppage of the flow of gold from the mines of California would weaken the credit and purchasing power of the Federal Government. Indeed, the annual shipments of $40,000,000 in gold and silver from San Francisco to the Northern States and to Europe constituted rich prizes.[1] Along the entire Pacific Coast of North America, from Panama to Vancouver Island, attempts were instigated to outfit privateers. Some ventures were authorized by the Richmond Government, while others were the mere aspirations of Confederate sympathizers. Two actual plots to intercept gold shipments were frustrated by the Pacific Squadron in co-operation with Federal and local officials in San Francisco and Panama. At San Francisco in March 1863, Asbury Harpending as a Confederate privateer, and in November 1864, at Panama, Thomas E. Hogg, a master’s mate in the Confederate States Navy, endeavoured to capture the Salvador in order to convert her into a Confederate raider.[2]

In addition to these two known plots, numerous rumours circulated that Confederate privateers were active elsewhere. Many such rumours emanated from British Pacific waters, and this factor, coupled with the Trent affair, caused an interesting exchange of diplomatic correspondence and at times created mutual fears on both sides of the far western Canadian border. A final incident in the diplomatic tangle was the appearance of the Confederate warship Shenandoah in the Pacific.

On May 11, 1861, the Duke of Newcastle, British Secretary of State, sent a confidential dispatch to James Douglas, Governor of Vancouver Island, stating that Her Majesty’s Government recognized the belligerency of the Southern States, and that instructions regarding questions likely to arise out of the conflict would be issued from time to time. The letter also stated that the naval forces should be impartial and grant neither party in the conflict any preference.[3] On May 16, Newcastle forwarded a copy of the Queen’s Proclamation of Neutrality to the Governor requesting that it receive the utmost publicity.[4] Two weeks later, instructions were circularized to prohibit both warring powers from carrying prizes into British territory.[5] On January 16, 1862, Newcastle informed the Governor that no belligerent ship was to be permitted to leave the same British port or harbour within twenty-four hours of the departure of any enemy ship, whether it be armed or unarmed. The Governor was also ordered to notify the commander of any armed vessel of this neutrality rule.[6]

The crisis resulting from the capture of the Trent created a war scare between the United States and Great Britain. On November 8, 1861, Commodore Charles Wilkes boarded the Trent upon the high seas near Havana and removed the Confederate Commissioners James M. Mason and John Slidell. The act was a definite violation of international law but was approved by the American people and the United States House of Representatives. Later the incident was successfully settled, but meanwhile the British prepared for possible hostilities.[7]

At Vancouver Island the British naval forces, as reported in December 1861, consisted of four vessels—the steam frigate Topaze, surveying ship Hecate, and gun-boats Forward and Grappler. All ships were seaworthy except the Forward, whose boilers needed repairs. In addition, there was a detachment of Royal Engineers stationed in British Columbia, and Royal Marines occupied the disputed San Juan Island. These two detachments together formed approximately 200 officers and men. Governor James Douglas related that the United States had no naval vessels in the vicinity except for one or two small revenue cutters. He possessed intelligence that the United States only had one artillery company in Oregon and Washington Territory, since the regular troops had been withdrawn.[8]

Governor Douglas wrote to the Duke of Newcastle stating that it would be impossible to defend the British possessions with the small forces available. Hence, he suggested that the best defence in the event of war would be an offensive action against Puget Sound by the naval vessels and such local auxiliaries as could be mustered. He believed that his plan would prevent the sending of any expedition against British possessions and would cripple United States trade and resources before any effective counter measures could be undertaken.[9]

Douglas pointed out the undefended coast and stated that the British fleet was capable of occupying Puget Sound without opposition. He further asserted that with reinforcements of two regiments of Her Majesty’s troops that there would be ” no reason why we should not push overland from Puget Sound and establish advanced posts on the Columbia River, maintaining it as a permanent frontier.”[10] The Governor also suggested the dispatch of naval units up the Columbia River to secure the occupation. He assured his home office in London that the scattered settlers would welcome any government able to protect them from the Indians. Douglas firmly believed in the practicability of the operation, conjecturing:

With Puget Sound, and the line of the Columbia River in our hands, we should hold the only navigable outlets of the country—command its trade and soon compel it to submit to Her Majesty’s Rule.[11]

The Victoria Chronicle, issue of February 4, 1863, published an article entitled “A Bold Plot,” in which appeared an account of the arrival of a commodore of the Confederate States Navy to Victoria the previous month. According to the story the commodore held a commission signed by Jefferson Davis authorizing him to purchase an English vessel to be outfitted as a privateer. The vessel was to be armed, and a crew recruited. Then the privateer would secretively sail from Victoria for the purpose of capturing a Panama-bound California steamer laden with a million dollars in treasure. The would-be privateers were to abandon their own ship and man the captured vessel, and either put the passengers aboard the privateer or ashore somewhere along the Mexican coast. Once their objective was accomplished, the privateers would abandon or scuttle the steamer and go ashore in Victoria or another British port with their newly acquired riches. However, the newspaper stated that the plan failed for lack of funds, and concluded with the following warning, which is interesting in light of the actual Chapman attempt at privateering occurring five weeks later in San Francisco:

Had not the funds fallen short, the ” bold privateer” might to-day have been afloat, and a treasure-freighted California steamer in a fair way of being sent to Davy Jones’ locker. As it is, no one has been hurt, and our San Francisco friends, remembering that ” fore-warned is fore-armed,” will, if they are wise, immediately guard against even the probabilities of the plot being carried to a successful consummation at some future time.[12]

On the same day a supposedly irate reader addressed a letter to the editor of the Chronicle which was printed the following day. The writer headed his letter ” The ‘ Bolt Plot,'” and signed it “A Confederate.” He admitted the recent appearance of a Confederate commodore with a commission, but protested the unjust charge that the passengers would have been treated as enemies. The author of the letter further claimed that Lincoln and his Cabinet had acknowledged the right of privateering by the Confederate States. He alluded to the respect previously accorded to private property and individual rights by Confederate privateers, and completed his retort:

I think, Mr. Editor, I may safely say that you now have no fears or apprehensions of a treasure freighted California steamer being sent to Davy Jones’ locker. So we think you need not forewarn or even advise your California ” friends” to kick until the rowel touches, for Greenbacks are somewhat under par now, and you might cause a depreciation. If you do honestly sympathize with them don’t give Uncle Abraham any unnecessary uneasiness, as I understand he has made another start for Richmond, and I am fearful he has taken the wrong road, and, as Bonaparte said, in crossing the Alps, the road is barely passable, for Uncle Abe has two Hills to cross, one Longstreet to traverse, one Stonewall to surmount, and then will have to enter the city on the Lee side, where, I am told, the wind is very unfavorable for Uncle Abe’s crafts. Most respectfully,

A CONFEDERATE[13].

A third party now entered the controversy, the rival newspaper, Victoria Colonist. Under the caption ” Confederate Privateer,” it accused their ” local contemporary ” of publishing numerous ” sensation items,” the latest of which was the story of a Confederate commodore attempting to purchase the steamer Thames. The Colonist labeled the story as ” perfect bosh,” and related that the only basis for the rumour had been the arrival from San Francisco of a certain Captain Manly who negotiated unsuccessfully the purchase of the English steamer for a firm engaged in the Mexican trade. The newspaper stated that the people have been deceived, and the United States authorities led to believe a privateer would sail from Victoria. The journal printed a letter from the firm S. & S. M. Holderness, dated January 7, 1863, San Francisco, which was addressed to Henry Nathan & Co. in Victoria. The letter revealed the intention of this San Francisco shipping firm to purchase the Thames and said that Captain Manly was being sent as their representative. The Colonist indicated that Messrs. Holderness wanted the Thames sent to San Francisco before purchasing it in Victoria, but the offer was not high enough. The newspaper also stated in reference to San Francisco, “A pretty place indeed in which to fit out a Confederate privateer! “[14]

In reply the Chronicle of the next day stated that they had not named Captain Manly as the commodore nor the Thames as the intended privateer. The newspaper asserted that they were ready to prove an attempt had been made to outfit a privateer and that a commodore had spent three weeks in Victoria. It also corrected an earlier statement that the plan failed for lack of funds, the real reason being disagreement among the ringleaders of the plot. The Chronicle challenged the correspondent ” Confederate ” or the Colonist’s editor to refute the truthfulness of the two articles published on the subject.[15]

The Colonist, on February 7, replied, repeating that her competitor published falsehoods. It charged that the Chronicle caused local Americans to distrust both Southerners and Englishmen, creating a situation in which espionage abounded in Victoria. In this regard the journal stated: “All that would be required would be an Alcatraz Island or a Fort La Fayette, with the power to arrest, to make Victoria like New York or San Francisco.”[16]

The Chronicle, in its issue of the same day, denied being a sensation sheet and printed another letter from its ” Confederate ” correspondent, identified as John T. Jeffreys, whom it described as a respectable Oregonian holding large interests in Cariboo. Jeffreys, in this second letter, wrote that he admitted as true everything stated by the Chronicle, except that the plan was of a piratical nature. However, he charged the editor with betraying a confidence when he exposed the plot. Beneath the letter the Chronicle announced that they had a signed letter from their informant authorizing them to publish whatever they thought proper. It further stated that Jeffreys could see the letter if he cared to call at the editor’s office.[17]

In the same issue of the Chronicle there appeared an article revealing a plot to seize the United States revenue cutter Shubrick. It stated that her commander, Lieutenant James M. Selden, was aware of the scheme to seize the cutter while en route through the sound to Port Townsend. The cutter was then to sail to Victoria, where Confederate privateers would board her. The article concluded that the vessel had not, up to late the previous night, arrived in Victoria, and it assumed that the plot failed because of the loyalty of Lieutenant Selden.[18] This issue also disclosed that the Thames was steaming for Barclay Sound and ” has not gone a-privateering, but still remains the property of Anderson & Co., of this city.”[19]

On February 9 the Colonist ridiculed the Chronicle for publishing Jeffreys’s letter. It referred to Jeffreys as a “veritable Baron Munchausen ” and the Chronicle as ” believers in nursery tales.” The journal also asserted that it possessed reliable information that no plot ever existed.[20] The next day the Chronicle related that they had been informed that Jeffreys, on the previous Sunday, February 8, told the editor of the Colonist, before witnesses, the truthfulness of his letter. It also asserted that Jeffreys was shown the evidence possessed by the Chronicle and was called upon to confirm or deny it.[21] On February 11 Jeffreys wrote a letter from the St. Nicholas Hotel to the editor of the Chronicle asking why he was requested to repeat what he had already stated. He asked whether or not the editor wished to hold his name to ridicule and, if such should be the case, suggested a duel. Once again Jeffreys reiterated his earlier statements concerning the plot. He concluded with the hope that he would not be consulted again and that friendlier feelings would develop between the two rival newspapers.[22]

The lengthy controversy of words in the columns of the two Victoria newspapers ended after ten days’ duration. The Colonist merely stated that there had never been a commodore in Victoria, and again referred to its rival as ” a sensation sheet” and its correspondent as ” a Confederate Baron Munchausen.”[23] The Chronicle assumed that this was an admission by the other newspaper that a plot at least existed.[24]

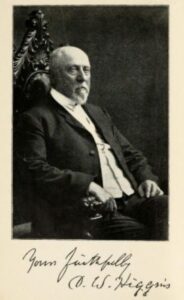

In 1904 David Willams Higgins, at the age of 70, who had been editor of the Chronicle in 1863, wrote a book relating his reminiscences. In a chapter entitled ” Sweet Marie,” he told the story of the supposed plot, which seems confusing in light of the newspaper controversy just presented. A summary of Higgins’s account appears pertinent He stated that soon after the outbreak of the Civil War many Southern sympathizers took up residence in Victoria. One group migrated to Cariboo and engaged in gold-mining and trading. Among these were two groups of brothers—Jerome and Thaddeus Harper from Virginia and John and Oliver Jeffreys from Alabama. They drove cattle from California and Oregon to British Columbia, making good profits.[25]

In Victoria the St. Nicholas Hotel, located on Government Street, became a meeting-place for Southern sympathizers. Higgins was a resident of the hotel. The Jeffreys brothers occupied Rooms 23 and 24, where they entertained Southern friends. Included among their friends were Mr. and Mrs. Pusey, Miss Jackson, and Richard Lovell. Higgins described Lovell as a handsome young man who claimed to be a Southerner. He was a good dresser and always perfumed his clothes. One evening the Jeffreys brothers and the Posey’s gave a party to which Higgins, Lovell, and Miss Jackson were invited. The ladies played music, and all sang ” Way Down South in Dixie ” and ” My Maryland.” The men and ladies both drank brandy and Hudson’s Bay rum.[26]

On another occasion a party was held celebrating a Confederate victory. When the celebration was over, John Jeffreys followed Higgins into his room, locked the door, and searched about to see that they were alone.[27] Then Jeffreys asked for Higgins’s assistance in a secret plan and told him that if he declined, he would have to take an oath not to reveal the scheme. Higgins at first refused but finally gave his pledge with a definite reluctance. Jeffreys then said:

We intend to fit out a privateer at Victoria to prey on American shipping. A treasure ship leaves San Francisco twice a month with from $2,000,000 to $3,000,000 in gold dust for the East. With a good boat we can intercept and rob and burn two of those steamers on the lonely Mexican coast and return to Victoria with five million dollars before the Washington Government will have heard of the incident.[28]

Higgins argued that such a scheme would constitute an act of piracy, and Jeffreys continued to say that he had letters of marque signed by Jefferson Davis and sealed by Judah P. Benjamin, the Confederate Secretary of State. He also told Higgins that a crew was ready, and that only a suitable ship was needed. Jeffreys asked Higgins to print an article in his newspaper which would mislead the United States Consul, Allen Francis [brother named Simeon Francis], and place the Consul’s detectives on the wrong trail. Higgins asked for time to decide, and Jeffreys left agreeing to return in a few days. After Jeffreys departed, Higgins smelled the awful perfume of Dick Lovell in the passage of the hotel.[29]

Higgins continued his story, telling how he regretted the fact that he allowed himself to hear the secret plan. He later refused to participate in the plot. He even related that Jeffreys challenged him to a duel and told how the fear of being killed haunted him. Eventually the plot was uncovered by detectives from the United States Consulate, who were none other than Richard Lovell and Miss Jackson, two guests at the gay parties held by John Jeffreys. As to the title of the chapter, ” Sweet Marie,” the author said that it was the name of the perfume used by Dick Lovell the Union spy, who had listened to the conversation held between Jeffreys and himself.[30]

According to Higgins the U.S.S. Shubrick was the vessel which the Confederates attempted to capture. It will be recalled that this plot was mentioned in his newspaper, the Victoria Chronicle of February 7, 1863. In his reminiscences Higgins stated that the Shubrick was engaged in customs and guard duty on Puget Sound. She sailed into Victoria, docking along the Hudson Bay Company’s wharf. Victor Smith, Collector of Customs for Puget Sound, discharged the officers and crew except Captain Selden and the chief engineer named Winship. Those discharged were suspected of being disloyal and of being involved in the plot. A new crew was hired, and the conspirators thus failed in their scheme.[31]

The fact that Higgins in his reminiscences did not mention the editorial controversy between his newspaper and the Colonist nor Jeffreys’s two letters would lead one to doubt the existence of a plot. However, when Jeffreys returned to United States territory in Oregon, he was arrested. On January 1, 1864, Brigadier-General Benjamin Alvord, commanding the District of Oregon, addressed a letter to Allen Francis, United States Consul at Victoria, referring to his appreciation of the Consul’s vigilance. Alvord requested that Francis try to obtain from Higgins “the original card” signed by John T. Jeffreys during the previous February which had been published in the Chronicle. The General wanted the original manuscript signed by Jeffreys and requested that it be sent to Edward W. McGraw, United States District Attorney at Portland, for it was needed as testimony against Jeffreys. Alvord also asked for the names of witnesses who could avow that Jeffreys participated in schemes against United States commerce and inquired whether Higgins would come to Portland in order to testify.[32]

The first alarm over rumours of privateering in Victoria signified by a United States authority occurred on February 25, 1863, when General Alvord dispatched a letter to the War Department in Washington, D.C, in which he called attention to the defencelessness of the Oregon and Washington coast. He stressed the need for heavy ordnance at the mouth of the Columbia River and urged that the Secretary of Navy send an iron-clad to the Columbia River. He stated that he had written to the Navy Department the previous September but had received no answer. Alvord pointed to the danger across the border in British territory of designs upon United States commerce. He enclosed in his letter a collection of newspaper items commenting on the Victoria Chronicle account of the plot to capture the Shubrick.[33]

The American State Department became gravely concerned about this rumour from Victoria, and the matter resulted in lengthy correspondence between Seward’s office and the British Legation. On March 31, 1863, Secretary Seward wrote to Lord Lyons:

I regret to inform you that reliable information has reached this department that an attempt was made in January last, at Victoria, Vancouver’s island, to fit out the English steamer Thames as a privateer, under the flag of the insurgents, to cruise against the merchant shipping of the United States in the Pacific. Fortunately, however, the scheme was temporarily, at least, frustrated by its premature exposure. In view, however, of the ravages upon the commerce of the United States in that quarter which might result from similar attempts which will in all probability be repeated, the expediency of asking the attention of her Majesty’s colonial authorities to the subject, in order that such violations of the act of Parliament and of her majesty’s proclamation may not be committed, is submitted to your consideration.[34]

Two days later Lord Lyons replied that he would immediately send a copy of Seward’s note to the Governor of Vancouver Island, which he did on the same day.[35] On April 15 Seward forwarded a second note to Lyons enclosing the following telegram he had just received from Ira E. Rankin, Collector of Customs at San Francisco:

Collector at Puget Sound reports plans for fitting out Privateers at Victoria, Secessionists very active and our Officers much alarmed, Colonial Authorities inform Consul that they cannot interfere with the fitting out of Privateers. Can anything be done to secure instructions from Home Government. I am trying to get Commanding Naval Officer to send steamer to the Sound.[36]

Lyons wired at once to William Lane Booker, British Consul of San Francisco, instructing him to write to the Governor of Vancouver Island in order to obtain assurance that all attempts at privateering would be stopped.[37] In the meantime the commandant’s office at Mare Island Navy Yard became apprehensive. Captain Thomas O. Selfridge ordered Lieutenant-Commander William E. Hopkins, commanding the U.S.S. Saginaw, to set sail for Port Angeles and Port Townsend, Washington Territory, and for Victoria. If the rumours were confirmed, Hopkins was told to prevent the escape of any privateer but was cautioned to heed the neutrality laws of Great Britain. After a certain lapse of time, the Saginaw was to coal at Bellingham Bay, and return to San Francisco.[38] Captain Selfridge telegraphed Gideon Welles, Secretary of Navy:

I have sent the Saginaw to Puget Sound on important service. The Cyane is here [Mare Island], and the Saranac at San Francisco, for repairs.[39]

Lord Lyons wrote again to Governor James Douglas at Victoria on April 16, stating:

The alarm and exasperation created by the proceedings of the Confederate Privateers, or ships of War, which have escaped from England, are so great that I am extremely desirous of being enabled to allay, as soon as possible, the anxiety which is felt, lest successful attempts should be made to equip similar Vessels in other parts of the Queen’s Dominions.[40]

On May 14, 1863, Douglas replied to Lyons’s communication, requesting that the President of the United States be informed that ” every vigilance ” would be used. Douglas stated that there was a report of a privateer being outfitted, but its truth was questionable. He also indicated that the vessel involved, the Thames, was not suited for that purpose.[41]

On June 3, 1863, Captain Thomas O. Selfridge reported to Secretary Welles on the reconnaissance tour of the Saginaw. The vessel had visited the principal ports of Washington Territory and Esquimalt. Commander Hopkins disclosed that the secessionists in the British possessions had gone undercover since the capture of the Confederate privateer Chapman at San Francisco. He further explained that there were no vessels plying the sound which were suitable for conversion into a cruiser or privateer. Hopkins reported one rumour to the effect that a small steamer, long overdue in port, had been purchased by Confederates, but indicated that it was not suited for privateering. At Esquimalt, Hopkins was unofficially informed that the Saginaw would be ordered to leave the port within twenty-four hours in accordance with Her Majesty’s neutrality laws.[42]

In his report, Captain Selfridge also included a letter from Allen Francis, United States Consul at Victoria, revealing the pleasure of United States citizens there caused by the appearance of the Saginaw. Francis mentioned that an English steamer, Fusi Yama, was due at Victoria, and was rumoured to have been purchased as a privateer. It was reported that the 700-ton vessel, a fast sailer, had munitions stowed aboard. Francis stated that the Chapman plot at San Francisco had created a sensation in Victoria, but he indicated that the activities of privateers had lessened.[43]

Not all rumours on the Pacific Coast disseminated from Victoria. There were even rumours in England that the United States was making military preparations in California designed to occupy British possessions north of Washington Territory. On May 19, 1863, a dispatch was sent from Downing Street to Governor James Douglas reporting that it had been assured by Secretary of State Seward that the rumours had no foundation.[44]

On October 16, 1863, Judah P. Benjamin, the Confederate Secretary of State, received a letter regarding the aspirations of a would-be privateer in British Columbia. A certain Jules David, president of the Southern Association of Vancouver Island and British Columbia, had been corresponding with James M. Mason, the Confederate Commissioner at London. He informed Mason about the organization of his Confederate society in Victoria and requested the grant of a letter of marque. Mason, who did not have the authority to issue letters of marque, referred David to the Confederate Government at Richmond. Heeding this advice, David wrote to Benjamin, asking permission ” to harass and injure our enemies,” and requesting that he immediately be sent a letter of marque, for the Southern Association had procured a strong and fast vessel of 400 tons and the funds to arm it. He also stated that in case the Confederate Government denied his request and preferred to send its own vessel to the Pacific Coast, the Southern Association would co-operate in assisting her. David believed that a privateer could easily prey upon United States commerce in the Pacific, as indicated by an extract from his letter:

The Federal Government have not force on this coast, and our privateers could do any amount of mischief without fear of capture. It is our most anxious wish to do something for our country, and we can not serve her better than in destroying the commerce and property of our enemies. If you will for a moment reflect upon the extensive commerce of the Federal States with South America, California, the islands, China, and Japan, you can well imagine what a rich field we have before us.[45]

Four days after Jules David penned his letter, the United States Consul at Victoria, Allen Francis, wrote to his brother, Major Simeon Francis, stationed at Fort Vancouver, stating:

We had a strange arrival here the other day. It was a vessel made entirely of steel. The masts were also steel. She was schooner rigged, of about 300 tons, and is said to be very fast. Since here arrival rumors have been rife that the rebels have been trying to buy her for a privateer, and it is further said that if they gave the price asked, they can have her.[46]

Francis also revealed that three weeks previously an English ship, the Jasper, arrived from Liverpool with 1,000 barrels of powder and shell, and it had been assumed by some individuals that a connection existed between the two events. He stated that it was a blunder not to have warships in the North Pacific, and that the only available ship was the brigantine Joe Lane, which had neither adequate speed nor armament. Francis further related that miners of secessionists sympathy were coming to Victoria from the Interior in desperate circumstances, and that the ” rebels ” were holding regular private meetings.[47]

Major Francis was absent from his station, and the Consul’s letter remained unopened for a month. On November 20, Brigadier-General Benjamin Alvord at Fort Vancouver sent a copy of the letter to army headquarters in San Francisco. Then he telegraphed General George Wright at Sacramento, requesting that steps be taken to send the U.S.S. Saginaw or another naval ship to Puget Sound. Alvord also recommended that the army send a copy of the letter to Admiral Charles H. Bell, aboard his flagship, U.S.S. Lancaster, or to the Commandant, Mare Island Navy Yard. Evidently Alvord was fearful that among the numerous miners returning to California for the winter there might be some conspirators boarding the steamers, which were heavily laden with gold shipments. However, Admiral Bell replied that he was unable to spare a vessel at the present time.[48] On November 23 Consul Francis assured General Alvord that he was exerting all efforts to quell any plot. He stated that the Confederate colony had increased because of the influx of miners from British Columbia, but he reported no alarming movements. Nonetheless, Francis noted the ease with which a vessel could be outfitted, since Vancouver Island had so many harbours. He again expressed his belief that the Government was negligent in not keeping a warship in the vicinity.[49]

Consul Francis continually received intelligence of Confederate plans to outfit privateers, and he had requested a warship on numerous occasions. Again in December 1863, he begged for the Saginaw. Upon arriving at Acapulco, Admiral Charles H. Bell received a communication from Commodore Charles H. Poor at San Francisco, relating that Francis possessed information concerning the outfitting of a privateer. As soon as the U.S.S. Narragansett completed repairs, Commodore Poor dispatched her to Victoria with instructions to the commanding officer, Selim E. Woodworth, to stop or capture the privateer. A number of sailors and marines from the U.S.S. Saranac and from Mare Island Navy Yard were transferred to the Narragansett in order to increase her complement to a full quota for the mission. The warship stood out of San Francisco on December 11, 1863, and Admiral Bell urged the Secretary of Navy either to cancel previous orders to send the Narragansett to Boston or to furnish him with another ship.[50]

The following February 20, General Richard C. Drum, located at army headquarters in San Francisco, addressed a letter to Governor Frederick F. Low of California regarding the use of the Narragansett. The letter stated that a number of prominent citizens had requested General George Wright to unite with Governor Low in sending a telegram to authorities in Washington, D.C, in order to advocate the retention of the vessel on the Pacific Coast.[51] Three weeks later the warship was undergoing repairs at San Francisco.[52] Eventually the vessel reached Vancouver Island, for, on April 22, 1864, Austin H. Layard, British Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, wrote to the Admiralty stating that the strictest neutrality should be enforced concerning the Narragansett’s movements within the limits of Vancouver Island.[53]

Consul Francis’s last mention of a rumour about a privateer was on November 18, 1864, when he wrote to Major-General Irvin McDowell Commandant, Pacific Division, relating that a large group of Southerners from British Columbia and Idaho Territory were gathering in Victoria. Their headquarters were in the ” Confederate Saloon,” and it was believed that they were machinating to procure a privateer. Francis also indicated that Governor Arthur E. Kennedy of Vancouver Island was co-operating with him to uncover the plot.[54]

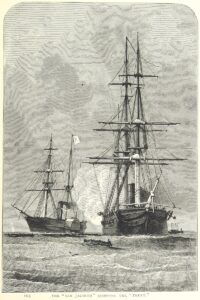

Rumours of Confederate privateers operating in Victoria stopped circulating during the final stages of the Civil War. However, British authorities in Victoria became concerned with one additional problem when the C.S.S. Shenandoah appeared in the North Pacific. This British- built raider had been recently refitted in Melbourne, and after the conclusion of the war continued her depredations against the American whaling fleet in the Arctic and North Pacific. On July 20, 1865, the whaleship Milo arrived in San Francisco with a party of survivors from the sunken whalers.[55] The next day the San Francisco journal Daily Evening Bulletin suggested, in an article entitled “A Chance for John Bull to do the Handsome Thing,” that a British gun-boat from Esquimalt should be sent in pursuit of the Shenandoah, for it would be three weeks in advance of any United States warship ordered in pursuit. The newspaper asserted that this would be ” an excellent stroke of policy ” by the British Columbian authorities, inasmuch as the ” pirate ” was armed and manned by Englishmen and made use of the English flag.[56] The Portland Oregonian of August 14 quoted an excerpt from the Victoria Chronicle, suggesting that protection be extended to the Shenandoah within the confines of law, but also expressing a desire for the early end of the ” career ” of the raider. The Oregonian protested this attitude in no uncertain terms and asked:

Do the Victorians now desire an opportunity to prove as faithless to the United States as their home did when it perfidiously sent the Shenandoah on her lawless cruise?[57]

On July 24 Consul Francis and Judge Lander of Washington Territory called on Governor Arthur E. Kennedy of Vancouver Island and asked him to dispatch a British warship to notify the Shenandoah of the fall of the Confederacy. However, the Governor replied that he could not act in the matter without official sanction.[58] Meanwhile the British Foreign Office forwarded a circular letter to Governor Kennedy, enclosing a letter of June 19 from James D. Bulloch, the Confederate naval agent at Liverpool, addressed to the commander of the Shenandoah. Bulloch’s letter contained instructions relative to the disposal of the ship.[59] Then on September 7 the British Colonial Office issued a circular dispatch to Governor Kennedy stating:

It is the desire of Her Majesty’s Government that the ” Shenandoah ” should be detained in any British Port which she may enter. If she should arrive in a Port of your Colony, you will notify to her Commander that it is incumbent on him to deliver up the vessel and her armament to the Colonial Authorities in order to be dealt with as may be ordered by Her Majesty’s Government. You will detain the vessel, by force if necessary, supposing that you have on the spot a sufficient force to command obedience. And, at all events, you will prohibit any supplies of any description to the vessel, so as to give her no facilities whatever for going to sea.[60]

On October 1 the Admiralty ordered British naval forces in the Pacific to detain the Shenandoah, provided she put into a port, or to seize her, if she were equipped as a vessel of war, upon the high seas. Rear-Admiral Joseph Denman was directed to treat the Shenandoah as a ” pirate,”[61] and his orders read:

You are at liberty to communicate these Instructions to the Commander of any cruizer [sic] of the United States’ Navy; and, without actually detaching any of the vessels under your command in pursuit of the ” Shenandoah,” you may render any assistance in your power in putting an end of the mischievous career of this vessel.[62]

On October 11 another confidential circular from the Foreign Office stated that if the Shenandoah was detained or captured, she should be delivered to the United States, but her crew could be allowed to go free.[63] While the search by the United States warships was still being made in the Pacific, the Shenandoah finally came to anchor in the Mersey at Liverpool on November 6, 1865.[64]

Although the alleged Confederate privateers in Victoria failed to outfit any vessel, the rumours of their activities did present a thorny problem in Anglo-American relations, for the United States did not welcome the British recognition of the belligerency of the Confederacy. Fortunately, no privateer appeared nor was outfitted in British Columbia, and her authorities were co-operative with the United States in investigating the rumours. Also, they must have been relieved when the Shenandoah discontinued her warlike moves. The only damage inflicted by Confederate plots along the entire Pacific Coast was to delay gold shipments and to entail expense to the United States in guarding her commercial route to the Isthmus of Panama.

Benjamin F. Gilbert.

San Jose State College, San Jose, Calif.

[1] Brainerd Dyer, ” Confederate Naval and Privateering Activities in the Pacific,” Pacific Historical Review, HI (1934), p. 433.

[2] Benjamin F. Gilbert, “Kentucky Privateers in California,” Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, XXXVM (1940), pp. 256-266; William M. Robinson, Ir., The Confederate Privateers, New Haven, 1928, pp. 272-289. British Columbia Historical Quarterly, Vol. XVIN, Nos. 3 and 4. 239

[3] Douglas to Newcastle, August 21,1861, MS., Archives of B.C.

[4] Newcastle to Douglas, May 16,1861, Circular Dispatch, Archives of B.C.

[5] Newcastle to Douglas, June 1,1861, Circular Dispatch, Archives of B.C.

[6] Newcastle to Douglas, January 16, 1862, Circular Dispatch, Archives of B.C.

[7] T. L. Harris, The Trent Affair, New York, 1896, passim; J. T. Scharf, History of the Confederate States Navy, New York, 1887, p. 662.

[8] Douglas to Newcastle, December 28, 1861, MS., Archives of B.C.

[9] Ibid

[10] Ibid

[11] Ibid

[12] Victoria Chronicle, February 4, 1863

[13] Ibid., February 5,1863.

[14] Victoria Colonist, February 5, 1863.

[15] Victoria Chronicle, February 6, 1863.

[16] Victoria Colonist, February 7, 1863.

[17] Victoria Chronicle, February 7,1863.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Victoria Colonist, February 9, 1863.

[21] Victoria Chronicle, February 10, 1863.

[22] Ibid., February 12, 1863.

[23] Victoria Colonist, February 13, 1863.

[24] Victoria Colonist, February 13, 1863.

[25] David William Higgins, The Mystic Spring and Other Tales of Western Life, Toronto, 1904, p. 107.

[26] Ibid., pp. 108-110.

[27] Ibid., p. 111.

[28] Ibid., p. 112.

[29] Ibid., pp. 113-114.

[30] Ibid.,pp. 116-126.

[31] Ibid., p. 123.

[32] Alvord to Francis, January 1, 1864, in Robert N. Scott (comp.), The War of the RebeUion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Washington, 1890-1901, Ser. I, Vol. L, pt. ii, pp. 714-715.

[33] Alvord to Thomas, February 25,1863, ibid., pp. 322-323.

[34] Seward to Lyons, March 31, 1863, enclosure in Booker to Douglas, April 17, 1863, MS., Archives of B.C. This was also printed in House Executive Document, No. 1, 38th Cong., 1st Sess., Pt. I, p. 535.

[35] Lyons to Seward, April 2, 1863, enclosure in Booker to Douglas, April 17, 1863, MS., Archives of B.C.

[36] Rankin to Seward, April 14, 1863, enclosure in Booker to Douglas, April 17, 1863, MS., Archives of B.C.

[37] Lyons to Booker, April 16, 1863, enclosure in Booker to Douglas, April 17, 1863, MS., Archives of B.C.

[38] Selfridge to Hopkins, April 23, 1863, in Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Washington, D.C, 1894- 1922, Ser. I, Vol. II, pp. 165-166.

[39] Selfridge to Welles, April 28,1863, ibid., p. 173.

[40] Lyons to Douglas, April 16, 1863, MS., Archives of B.C.

[41] Douglas to Lyons, May 14,1863, MS., Archives of B.C.

[42] Selfridge to Welles, June 3, 1863, in Official Records . . . Navies, Ser. I, Vol. n, pp. 259-260.

[43] Francis to Selfridge, May 13, 1863, ibid., p. 260.

[44] Lyons to Russell, April 27, 1863, enclosure in Newcastle to Douglas, May 19, 1863, MS., Archives of B.C.

[45] Jules David to Benjamin, October 16, 1863, Official Records . . . Navies, Ser. H, Vol. HI, pp. 933-934.

[46] Francis to Major S. Francis, October 20, 1863, in R. N. Scott, op. cit., Ser. I, Vol. L, pt. ii, p. 678.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Alvord to Francis, November 20, 1863, ibid., pp. 679-680.

[49] Francis to Alvord, November 23, 1863, ibid., p. 682.

[50] Bell to Welles, January 9, 1864, in Official Records . . . Navies, Ser. I, Vol. II, p. 583.

[51] Drum to Low, February 20, 1864, in R. N. Scott, op cit., Ser. I, Vol. L, pt. ii, p. 761.

[52] Poor to Wright, March 15, 1864, ibid., pp. 789-790.

[53] Layard to the Admiralty, April 22, 1864, enclosure in Layard to Rogers, April 23, 1864, enclosure in Cardwell to Kennedy, April 30, 1864, MS., Archives of B.C.

[54] Francis to McDowell, November 18, 1864, in R. C. Scott, op. cit., Ser. I, Vol. L, pt. ii, p. 1061.

[55] San Francisco Daily Alta California, July 21, 1865.

[56] San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin, July 21, 1865.

[57] Portland Oregonian, August 14, 1865.

[58] Victoria Colonist, July 26, 1865.

[59] Cardwell to Kennedy, July 5, 1865, with enclosures Bulloch to Commander of Shenandoah, June 19, 1865; Mason to Russell, June 20, 1865, Circular Dispatches, MS., Archives of B.C. The second enclosure was a request by the Confederate agent, James M. Mason, to send instruction to the Shenandoah via British diplomatic channels to the possible places where the vessel might stop. These places were Nagasaki, Shanghai, and the Sandwich Islands.

[60] Cardwell to Kennedy, September 7, 1865, ibid.

[61] Cardwell to Kennedy, October 11, 1865, with enclosures Romaine to Denman, October 1, 1865, and Law Officers of the Crown to Russell, September 21, 1865, ibid.

[62] Romaine to Denman, October 1, 1865, ibid.

[63] Cardwell to Kennedy, October 11, 1865, ibid.

[64] Cornelius E. Hunt, Cruise of the Shenandoah, New York, 1867, p. 247, see also J. T. Scharf, op. cit., p. 811.

A copy of the letter James Douglas wrote to the Duke of Newcastle, December 28, 1861, outlining how England could regain US lands given up through the Oregon Treaty of 1846.

James Douglas to Pelham-Clinton, Henry Pelham Fiennes, 5th

Separate, Confidential

28 December 1861

It is commonly reported by the Newspaper Press in California, and on the authority of those Prints, repeated here, that a British Steam Packet variously stated as the “Fingal”, and by other accounts the “Trent” was boarded some time last month, on the high seas by an armed party detached from the United States Corvette “Jacinto” under the Command of Commodore Wilkes; and that the Confederate Commissioners, Messrs. Mason and Slidell, who were among the passengers on board, were, in violation of international Law and the rights of the Flag, seized upon and forcibly removed, notwithstanding the protest of the Master, who had no means of resisting the violence by which he was threatened.

- As it is feared that complications may grow out of so rash and insolent an act, Endangering our friendly relations with the United States, I think it incumbent on me to review our means of defence, and the course which ought to be taken by this Government in the event of hostilities being declared.

- The Naval Force at present here, consists of Her Majesty’s steam Frigate “Topaze”, Captain The Honble J.W.S. Spencer; the “Hecate” Surveying Ship; with the “Forward” and “Grappler” Gun Boats. With the exception of the Forward, whose boilers are worn out and unserviceable, these Ships are all in a thoroughly efficient state.

- Our Military Force consists of the Detachment of Royal Engineers stationed in British Columbia, and the Royal Marine Infantry occupying the disputed Island of San Juan; forming in all about 200 rank and file.

- The United States have absolutely no Naval Force in these waters, beyond one or two small Revenue Vessels; and with the exception of one Company of Artillery, I am informed that all their regular Troops have been withdrawn from Oregon and Washington Territory; but it must nevertheless be evident that the small Military Force we possess, if acting solely on the defensive, could not protect our Extensive frontier even against the Militia or Volunteer Corps that may be let loose upon the British Possessions.

- In such circumstances conceive that our only chance of success will be found in assuming the offensive and taking possession of Puget Sound with Her Majesty’s Ships, re-inforced by such bodies of local auxiliaries as can, in the Emergency, be raised, whenever hostilities are actually declared, and by that means effectually preventing the departure of any hostile armament against the British Colonies, and atone one blow cutting off the Enemy’s supplies by sea, destroying his foreign trade, and entirely crippling his resources, before any organization of the inhabitants into military bodies can have effect.

- There is little real difficulty in that operation, as the Coast is entirely unprovided with defensive works, and the Fleet may occupy Puget Sound without molestation.

- The small number of regular Troops disposable for such service would necessarily confine our operations to the line of coast: but should Her Majesty’s Government decide, as lately mooted, on sending out one or two Regiments of Queen’s Troops, there is no reason why we should not push overland from Puget Sound and establish advanced posts on the Columbia River, maintaining it as a permanent frontier.

- A Small Naval Force entering the Columbia River at the same time would secure possession and render the occupation complete. There is not much to fear from the Scattered population of Settlers, as they would be but too glad to remain quiet and follow their peaceful avocations under any government capable of protecting them from the savages.

- With Puget Sound and the line of the Columbia River in our hands, we should hold the only navigable outlets of the Country, command its trade and soon compel it to submit to Her Majesty’s Rule.

- This may appear a hazardous operation to persons unacquainted with the real state of these Countries, but I am firmly persuaded of its practicability; and that it may be successfully attempted with a smaller force, than, in the event of war, will be required to defend the assailable points of our extensive frontier, which will be attacked on all sides if we remain entirely on the defensive, and neglect to provide full occupation for the Enemy at home.

- In any case it will be my first duty, on war being declared, to provide for the defence of Her Majesty’s Possessions by raising and organizing a local Militia to co-operate with Her Majesty’s regular Forces. The people will no doubt be prepared to make many sacrifices on behalf of their Country, but even with the best possible disposition on their part, funds will be wanted for the Equipment and Sustenance of such a force which it is utterly impossible for this Colony to furnish. I therefore beg Your Grace will be pleased to favor me with definite instructions on this point, so that I may be in a position to take every advantage of circumstances and may not involve Her Majesty’s Government in any Expenditure for which they may be unprepared.

I have the honor to be

My Lord Duke,

Your Grace’s most obedient

and humble Servant

James Douglas

Citation: Douglas, James to Pelham-Clinton, Henry Pelham Fiennes 28 December 1861, CO 305:17, no. 2297, 570.The Colonial Despatches of Vancouver Island and British Columbia 1846-1871, Edition 2.4, ed. James Hendrickson and the Colonial Despatches project. Victoria, B.C.: University of Victoria. https://bcgenesis.uvic.ca/V61078CO.html.