The Early Militia and Defence of British Columbia, 1871-1885

B.C. Historical Quarterly, January-April 1954, Vol. XVIII, Nos 1 &2

Reginald H. Roy – Provincial Archives, Victoria, B.C.

When the Crown Colony of British Columbia entered into confederation with the Dominion of Canada in 1871, the problem of its defence was automatically assumed by the Federal authorities. At that time there existed in British Columbia, at least in name, three militia units. In the Provincial capital was the Victoria Rifle Corps, a unit formed in the summer of 1864, consisting of two companies, each of which once had a peak strength of some forty-five men. On the Mainland, in New Westminster, were two militia companies. The New Westminster Volunteer Rifles had been formed in November 1863. In its ranks were to be found many men who had served with the recently disbanded detachment of Royal Engineers.[1] The Seymour Artillery Company, also of New Westminster, was organized in July, 1866, as a direct result of the Fenian scare in the East, but it was not until a year later that this company received its main armament—two 24-pounder bronze cannon.

The artillery and infantry companies were, as their names suggest, composed entirely of volunteers. Then, as now, interest in the militia units was governed mainly by the imminence of internal or external danger to the colony. Thus, during the time of the Fenian scare in 1866, the militia ranks had been swelled to their greatest numbers. As fears of such a raid subsided, interest in the companies waned and their strength melted as a consequence. In many respects the attention paid the militia by the local government and the Colonial Office paralleled that in the colony itself. At the height of the Fenian scare the War Office shipped a supply of guns, rifles, ammunition, and equipment to the colony, most of which, when it arrived in 1867, was used to outfit the New Westminster companies. No comparable supply of warlike stores reached British Columbia again until six years later. The colonial government, whose past financial grants to the militia companies were both few and meagre, was delighted at the response to the threatened Fenian raid. Not only did the men enrol in the militia, but they purchased their own uniforms and contributed toward the maintenance of the companies. This spirit of sacrifice, applauded but unmatched by the colonial legislature, subsided into an apathy and neglect from 1867 onwards.

By 1871, therefore, the militia in British Columbia was but a shadow of its former state. Armed with outmoded muzzle-loading rifles,[2] ignored by the authorities in London, faced with indifference at home, the companies were weak in morale, strength, armament, and training. With no effective military force available, the defence of the Pacific Coast rested with such British naval vessels as were present at the Esquimalt naval base. Here, too, the situation was not always satisfactory. The Pacific Squadron was responsible for the protection of British interests in a sea area covering many thousand square miles, and the troubled waters off South America frequently denuded the British Columbia coast of all but one or two gun-vessels. Indeed, such was the situation when, a few months after its confederation with Canada, an incident occurred which was to emphasize the defenceless state of British Columbia and which, ultimately, was to hasten the establishment of the first Canadian militia forces in the Province. On December 31, 1871, the Lieutenant-Governor of British Columbia, Joseph W. Trutch, received an anonymous letter which read as follows:

Victoria, B.C. To His Honor the Lieutenant-Governor …. 29th December 1871

Sir: There are now in town a Company of Fenians who hold regular meetings and are well drilled. Take a warning—they are now in part of the Dominion and will have revenge yet from the Canadians. Several of the Government Rifles and Bayonets are in their hands, also some of the ammunition for Long Enfield Rifles. This, Sir, is a warning. You may treat it as you think, but it is true, nevertheless. [Signed] ” From a Loyal Subject in Victoria”[3]

Upon receipt of this warning, and after a hurried meeting with his Executive Council, the Lieutenant-Governor took immediate steps to forestall any Fenian raid from within or without. On New Year’s Day he sent a message to Captain R. P. Cator, R.N., then Senior Naval Officer at Esquimalt, advising him of the warning note he had received. In this message he stated he did not seriously apprehend any such attack to be impending, but he added:

“… In view of the events which happened in 1870 in the Province of Quebec and still more recently in the Province of ” Manitoba” and the known character and aims of the Fenian organization, I think it incumbent to take such steps as are in our power to prevent the perpetration of robbery and outrage in our neighborhood.[4]

Under the circumstances, therefore, Trutch requested Cator to station the gun-vessel H.M.S. Boxer[5] in Victoria Harbour and to take any further steps he thought advisable after consulting with the Attorney- General, Honourable J. F. McCreight, the bearer of the message.

Captain Cator’s action was prompt. The Boxer was immediately sent to the harbour, but, after further consultation, a more elaborate scheme of defence was worked out. H.M.S. Sparrowhawk[6] was directed to lay off the harbour-mouth to prevent the entry or exit of all boats and vessels to and from the harbour until satisfied they were engaged in lawful business. It would also render assistance should there be any attack on Victoria. The Sparrowhawk was also to keep a lookout for a signal made by those on shore should the Fenians attack from an unexpected quarter. In such a case, the Victoria Police were to fire a series of rockets from the Government Buildings. On seeing this signal, the Sparrowhawk would fire three guns in succession. This would both answer the signal on shore and at the same time alert the ships in Esquimalt. On hearing the signal guns H.M.S. Boxer was to get up steam immediately and call alongside the Scout[7] and Sparrowhawk for the purpose of collecting a party of fifty Royal Marines. These men, under the command of Lieutenant Hume, R.M.L.I., would be rushed to Victoria and landed near the Government Buildings, while the Boxer would proceed up the harbour to act as the circumstances warranted.[8] The plan of defence, awkward as it appears, was probably as effective a plan as was feasible at the time. In Victoria the government was unable to call upon the militia to render assistance,[9] and the available handful of police was little more than a token force. Captain Cator had his own problems, too, since in case of a raid it would be his special duty to guard the Esquimalt naval base, and for that purpose he would require a large part of the naval force under his command. As he pointed out to Trutch:

“. . . Without some more efficient force than now exists in Victoria it is evident that such outrages as are alleged to have been intended, may be organized with impunity in your midst, and I cannot but suggest that this force should be so increased and reorganized as to furnish a real protection to life and property, and so prevent the re-occurrence of such alarms as we have been subject to lately. I would also bring before your notice the very exposed position of British Columbia, with scattered towns which would be unable to afford each other assistance in consequence of their distance apart, and the whole appearing to me entirely dependent for protection in case of outbreak or raid on what little assistance that can be offered by Ships of War present at Esquimalt. This I attribute to the entire absence of any Military force in the Province and would again suggest that Victoria should be made the depot of a well organized body of Militia and Police, not only for the protection of that town, but such as to be able to render assistance in case of emergency to other parts of the Colony [sic.[10]

These military facts of life had already become glaringly apparent to Trutch and his Executive Council. On January 2, with the Sparrow- hawk patrolling the harbour-mouth and the Boxer, with steam up and guns ready for action, stationed inside the harbour, Trutch wrote Joseph Howe informing him of the steps he had taken.[11] These measures seem to have been effective, for if there was any factual basis for the warning— and certainly the Victoria Police could find none—the naval preparations would appear to have forestalled any proposed raid. Local interest in the scare quickly subsided, but although it was soon treated as a joke, newspaper comment expressed the hope that the Province might soon have better protection.

Stronger defences were also uppermost in the minds of the Executive. At the meeting held on January 2 it was decided that in view of the inadequate state of the militia and the uncertainty of lithe naval protection afforded by the warships at Esquimalt, the Dominion Government should be urged to take the following steps. First, every effort should be made to induce the Imperial Government to make Esquimalt the permanent headquarters station of the British North Pacific Fleet, and to agree to keep, in addition to the gun-vessels detailed for service in British Columbia waters, at least one heavy frigate. Further, the Canadian militia system should be extended to the Province and a regular force of 100 men stationed there. Finally, the Executive asked for a reliable detective to keep watch on the Fenians and report their intentions or movements[12].

In communicating these views to the Federal authorities, Trutch pointed out that British Columbia, and especially Victoria, was more exposed to a hit-and-run attack than perhaps any other portion of the Dominion. Not only would an attack by sea give aU the advantages of concealment and surprise to the enemy, but the geographical remoteness of British Columbia from the rest of the Dominion made any hope of timely aid out of the question. Under such circumstances, and until an efficient militia force was organized, the Navy formed not only the first but the only line of defence. If the Province could rely upon the Navy having a minimum of two gun-vessels and a frigate present at Esquimalt, then, thought Trutch, it would be impracticable for any party of marauders to get away from the Island even if they should overpower those on shore. However, as matters stood, H.M.S. Scout was under orders to go to the Sandwich Islands in March, and the Admiralty had intimated a few months previously that it wanted the Sparrowhawk removed from the station.[13]

Part of Trutch’s fears, however, was soon dispelled. On January 20 word was received in Ottawa that the Admiralty had decided to leave the Sparrowhawk at Esquimalt for the present, and, further, that a vessel of similar tonnage and armament would replace her when that vessel was recalled.[14] Meanwhile, the gun-vessel still remained on guard outside the harbour-mouth, waiting in vain for the Fenians. At the end of the month the Executive Council reconsidered the necessity of keeping the Sparrowhawk at its station. Trutch suggested to Cator that, in view of the severe weather, the ship might be anchored within the harbour itself, but Cator countered with the proposal that the vessel should be withdrawn altogether. Despite every appearance of continued peace and calm, Trutch remained cautious and tartly replied that he had not received any information “… as would warrant the conclusion that the special protection offered during the past month by the Naval Force under your command can be dispensed with, without risk of life and property in the city.”[15] A gun-vessel continued to guard Victoria until the end of February, but target practice provided the only break in the monotony for its officers and crew.

In Ottawa, meanwhile, Trutch’s correspondence and the obvious need of a system of defence in British Columbia had come to the attention of the Minister of Militia and Defence, Sir George E. Cartier. It was the opinion of the Adjutant-General of Militia, Colonel F. Robertson-Ross, that for the present time a quota of no more than 500 militia- men should be raised in Military District No. II.[16] However, he suggested that for ” prudential reasons ” a depot consisting of sufficient arms, equipment, and ammunition for 1,000 men should be formed in Victoria immediately. This suggestion was acted upon, and on February 26 an order for arms and equipment was sent to England. Although no cannon were included in the purchase, the arms ordered were the latest type of breech-loading Snider rifles.[17]

The choice of a suitable commander for British Columbia fell ultimately on Charles F. Houghton. An Irishman by birth, Houghton had served as a commissioned officer in the 57th and 20th Regiments of Foot, both in England and abroad. In 1863, at the age of 25, he sold his commission and came to British Columbia, where he took up farming in the Okanagan Valley. In 1871 he was elected a member to the House of Commons, and it was in Ottawa that he heard the appointment of Deputy Adjutant-General for Military District No. 11 was to be filled.[18] His application for the position was strongly supported by his fellow members of parliament from British Columbia, and at the end of the session, after talking to Cartier, Houghton returned home in June confident his appointment would take place immediately. The decision to appoint Houghton to the vacant post was delayed by the proposed visit of the Adjutant-General to British Columbia to survey the military situation there for himself. Robertson-Ross arrived in Victoria for a two-week visit on October 28, 1872. In his report he suggested the formation of two companies of militia at Victoria, one in Nanaimo, New Westminster, and Burrard’s Inlet, and the reorganization of the almost defunct artillery company at New Westminster.[19] The death of Cartier once more delayed Houghton’s appointment, and consequently the implementation of the Adjutant-General’s recommendations. It was not until March 21, 1873, that Houghton was given the rank of Lieutenant-colonel and designated the Deputy Adjutant-General of British Columbia.[20]

The arms and equipment from England did not reach Victoria until the summer of 1873, and since the town possessed neither magazine nor armoury, they were stored in private warehouses until that situation was remedied. In October, Houghton received authority to proceed with the raising of five companies of militia; the two in Victoria were limited to an enrolment of fifty other ranks, while a limit of forty militiamen was placed on the rifle companies in the other centres. These men were to be raised, drilled, and paid under the same militia system existing in the rest of the Dominion. To encourage the formation of the new corps, band instruments were purchased to help raise the martial spirit, and both a rifle range and drill-shed were promised, providing the land was donated by the several municipal authorities.

The formation of the rifle companies at Victoria and New Westminster was completed with little difficulty. Nos. 1 and 2 Company of Rifles at Victoria came into existence on February 13, 1874. No. 1 Company of Rifles at New Westminster was posted in orders on the same day.[21] The Company at Nanaimo was not formed until some months later. The method used by Houghton to raise this company was quite typical of the times. He journeyed to Nanaimo on April 14 and, he wrote:

“On arrival … I immediately posted notices and convened a public meeting at the Court House on the evening of the 16th. On which occasion, having explained the Militia Act and Regulations to them, I succeeded in enrolling seventeen volunteers. At a subsequent meeting held at the same place I enrolled nineteen more names, making a total in all of thirty-six, from which number I selected a Captain, Lieutenant and Ensign in whose hands I placed the roll for completion.”[22]

A further problem Houghton had to deal with was the lack of a drill instructor for the Nanaimo company. For a short time, a private from one of the Victoria companies, himself newly trained, drilled the volunteers, but it was feared, with good reason, that he was likely ” to do as much harm as good.”[23] Finally the services of a gunner’s mate from H.M.S. Myrmidon, then stationed at Esquimalt, was acquired for six weeks, and No. 1 Company of Rifles at Nanaimo set to work with a will.

The summer of 1874 also saw the formation of the Seymour Battery of Garrison Artillery in New Westminster.[24] Although provided with new uniforms and rifles, the battery—actually a half-battery—had only the two outmoded 24-pounder howitzers for its main armament. Moreover, the field carriages on which these bronze cannon were mounted and the harness needed to pull the carriages were fast deteriorating through long neglect.

Once the new militia was organized in British Columbia, the need for drill-halls, magazines, and rifle ranges in Victoria, New Westminster, and Nanaimo became pressing. By June 1874, tenders for the construction of a drill-shed in Victoria had been received, and work on the building began in August. When completed in December it cost almost $4,500. Measuring 112 by 64 feet, it had a large central hall with five rooms on either side containing offices and storerooms. At either end of the hall was a door, one acting as the front entrance, while the other led to a cleared plot of land at the rear which was used for drill purposes.[25]

A magazine for the storage of ammunition, powder, and explosives was built several years later. For some time, the Hudson’s Bay Company rented space on their powder-barge at Esquimalt for military stores, but by 1878, after paying well over $3,000 in rentals, the Government decided it would be cheaper to construct their own magazine. At first it was proposed to build one on Government land within the city, but the protests of the City Council, supported by the opinion of the Provincial Premier, who thought the new magazine would be much too close to the Parliament Buildings, resulted in a change of plans. Beacon Hill, a site situated on the outskirts of the city, was finally chosen, and construction of the $1,200 building began in February 1879. When completed four months later, it was used to store artillery as well as small- arms ammunition.[26]

In Nanaimo the militia company waited in vain for its drill-shed. For several years the company used the small ” Mechanic’s Hall ” as a poor substitute, and even this was denied them in 1878, when they were forced to use a sash and door factory for their drill. There is little doubt that this lack of proper facilities contributed in no small measure to the losing struggle for existence of this small company. The Nanaimo militiamen had built their own rifle range without government aid, but their enthusiasm waned as the years passed without any indication of Federal assistance.[27]

New Westminster was for a short time sightly better off than Victoria or Nanaimo. A drill-shed had been built there by the colonial government in 1866 for the volunteers. Moreover, the Royal Engineers had constructed a magazine in the town, a brick and stone building with copper doors. Both these buildings were taken over by the New Westminster units in 1873, and although their foundations were even then beginning to sag, they served their purpose for several years.

During this time, and indeed for a number of years thereafter, there were no militia units in the Interior of the Province. When he made his western inspection tour in 1875, Major-General E. Selby Smyth, commander of the Canadian militia, was asked to establish some sort of a protective force at Kootenay Village and Joseph’s Prairie. Kootenay lay west of the Rockies and was some 600 miles journey from the Provincial capital. In this position—” one of the most isolated portions of the British Empire,” as the general aptly described it—a small white population of about 150 was surrounded by almost six times their number of Indians. Smyth recommended the establishment of a police force of fifty men in the area, but no further action was taken. He also thought it desirable to establish a small corps of mounted infantry or riflemen at Kamloops, and further suggested raising additional small corps at Clinton, Cache Creek, and Okanagan. These latter units, he said, could drill once a month independently, and once a year the whole could assemble at Kamloops and drill together with the mounted rifles.[28]

Although Smyth was thinking in terms of an available force to quell internal disturbances, another British officer looked on the lack of militia in the Interior as a dangerous gap in the southern defences of the Province. Colonel G. F. Blair, late Royal Artillery, had been sent to British Columbia to survey the sites for possible defensive works at Victoria and Esquimalt. At the request of the Federal authorities, he wrote what is possibly the first military intelligence report of British Columbia. The problem of defending the seaboard he thought beyond the resources of the Dominion and felt it must be left in the hands of the Imperial Government. It was the southern frontier which demanded most attention from a strictly military point of view. If, through an unfortunate series of circumstances, relations with the United States deteriorated to the point of war, Blair wrote that:

“. . . in the present state of things a Regiment of United States Light Infantry, preceded by a Corps of Indian Guides and supported by a battery of light rifled mountain train guns, with a transport of Indian pack horses or mules marching by the Whatcom trail, could seize upon and paralyze the communications of the whole country, viz. the New Westminster and Hope wagon Road and the Lower or Navigable portions of the Fraser, i.e. all below Fort Hope.”[29]

This would be but a prelude to the main action, which Colonel Blah- envisaged as a sweep by a larger force cutting off and enveloping the more populous coastal towns from the east, while at the same time an American naval squadron would land troops on Vancouver Island to take Esquimalt, Victoria, and Nanaimo from the rear. The establishment of a corps of guides along the southern frontier, having a nucleus composed of the ex-Royal Engineers who had settled in the Sumas and Matsqui areas, was deemed essential by Blair, together with a survey of the frontier from a military point of view.[30]

Both Colonel Blair and General Smyth were unanimous in their recommendation that Victoria and Esquimalt should be protected by artillery, for in the absence of a ship-of-war at the naval base there was nothing to prevent an enemy cruiser from destroying either place with no fear of retaliation. While on his inspection tour, Smyth noted two 7-inch and four 40-pounder muzzle-loading rifled guns at the naval dockyard about to be sent back to England as obsolete for naval service. He proposed, therefore, that they be transferred to the Dominion Government and be used to arm an earthwork battery he would have constructed at Macaulay’s Point, a commanding promontory midway between Victoria and Esquimalt Harbours. Should such a battery be established, he reported, no vessel but an iron-clad would venture to run the gauntlet of its fire, and even such a ship would have its unarmoured decks exposed to the plunging fire the battery would deliver.

Despite the obvious need of establishing land batteries to defend the naval base and Provincial capital, no action was taken on the general’s suggestion either by the Admiralty or the Dominion Government. Indeed, every effort was needed to keep the present militia companies in a proper state of efficiency. The financial depression of the seventies, combined with the steadily improving relations with the United States, reduced militia expenditure almost by half, and cut by more than a third the number of trained militia.[31] In British Columbia, as elsewhere, the effect of such a parsimonious budget was evident in the ill-fitting and worn uniforms of the men, the reduced amount of ammunition allowed for annual target practice, and in other similar ways, which decided many men against re-enlisting when their three-year term of service was completed in 1876. Nevertheless, the companies continued to function as new volunteers stepped forward to fill the places of the disgruntled minority who left. Colonel Houghton even received applications requesting the formation of two additional militia companies on the mainland, but these had to be turned down, since there were scarcely sufficient funds to support existing companies.[32]

The threat of a Fenian raid had caused the Federal Government to hasten the formation of militia companies in British Columbia in 1872; five years later it was another threat of a raid—this time by Russian war vessels—that caused both the Dominion and British Governments to look on British Columbian defences with renewed interest.

In Europe the long-smouldering Balkans had burst into flame when Russia declared war on Turkey in April 1877. Britain’s relations with Russia worsened steadily as Russian troops drove toward Constantinople and the Bosporus. To counter what was regarded as an intolerable threat to her Near Eastern possessions, Great Britain took strong military and naval measures which clearly indicated her determination to prevent Russia’s domination of Turkey.

The danger of war with Russia led Britain to review the defences of her empire as a strategic whole. It was very obvious that despite her immense naval power and resources, the Royal Navy and the widely scattered British garrisons would be unable to prevent damaging attacks on her possessions by enemy naval forces. In March 1878, a secret circular dispatch was sent from the Colonial Office pointing out the necessity for the various colonies to be in readiness to protect themselves as far as possible in the event of the outbreak of hostilities. Should war ensue, the dispatch warned:

“The danger against which it would be more immediately necessary to provide would be an unexpected attack by a small squadron or even a single unarmoured cruiser, with the object of destroying public or private property . . . rather than any serious attempt at the conquest or permanent occupation of any portion of the colony.”[33]

The danger of a hit-and-run attack by Russian naval forces had been brought quite forcibly to the attention of British Columbia a month before this dispatch was sent. On February 9 the newspapers reported the arrival in San Francisco of a Russian naval squadron.[34] This, combined with reports of increasing tension in Europe, created considerable apprehension in Victoria, especially as the major portion of the Esquimalt-based squadron was cruising in South American waters. In view of these circumstances, a special meeting was held by the Premier of British Columbia with the senior naval and militia officers, at which it was decided to organize a corps of volunteer artillery. Captain F. C. B. Robinson, R.N., then Senior Naval Officer at Esquimalt, promised to supply guns, which would be placed at selected points covering likely approaches to the harbours, and also agreed to loan the services of a naval artillery instructor to train the corps. Volunteers for the new corps quickly filled its ranks, and within a few days the artillery unit started holding regular drill parades.[35]

While these pro terns, arrangements were being made on the Pacific Coast, the arrival of the Russian steamer Cimbria at Ellsworth, Maine, caused considerable apprehension in Ottawa. According to the Commander of the Militia, Major-General E. Selby Smyth, the Cimbria, manned by 60 officers and 600 seamen, had on board a cargo of guns and warlike stores which were to be used to arm fast steamers purchased in the United States which, in the event of war, would be used against British shipping in the Atlantic. While warning that the Atlantic ports must be put in a proper state of defence, Smyth did not forget the vulnerable Pacific Coast. In this respect he added:

“I have so frequently brought to notice the totally unprotected state of the harbour of Victoria and the entrance to Esquimalt in Vancouver Island as well as the immensely important coal mines of Nanaimo that I need only once more very earnestly urge that guns now lying in Esquimalt Dockyard . . . may at length be handed over and mounted on Macaulay’s Point to command the entrance to both harbours.”[36]

Smyth’s long battle to have the spare cannon at Esquimalt released for land defence had been won even as he wrote the above. A study of the defensive needs of Vancouver Island had been undertaken by a Colonial Defence Committee in Great Britain earlier in the year. Spurred by the danger of war with Russia and appreciating the remoteness of the Pacific ports and the time lapse before its recommendations could be put into effect, the Committee made a special early report on Victoria and Esquimalt. In view of the fact that Esquimalt was ” the only refitting station in British territory on the western coast of America,” the Committee recommended that some eighteen medium and heavy guns should be sent out from England for the protection of the two ports. Since this would take considerable time, the Committee suggested that the Admiralty should loan such available armament at Esquimalt to the Dominion as could be spared. The guns were to be loaned only until they could be replaced by those sent from England or until required for use by Her Majesty’s ships. The letter from the Colonial Secretary accompanying the Committee’s report informed the Dominion Government that the Admiralty had agreed to the loan, and that ” the whole armament in store at Victoria and Esquimalt, whether belonging to the War Office or the Admiralty, will be at the disposal of the Dominion Government for the defence of these points.”[37]

The Admiralty’s decision, cabled to Ottawa, permitted Major-General Smyth to take the first concrete steps toward setting up a system of land defences for Victoria and Esquimalt. On May 11 he ordered Lieutenant- Colonel D. T. Irwin, Inspector of Artillery, to proceed immediately to British Columbia to supervise the construction of the proposed coastal batteries.

Irwin arrived in Victoria on May 27, and on the same evening attended the first regular enrolment of the volunteer artillery company. About thirty men enlisted that night, and within a few weeks the new corps was up to its establishment of fifty all ranks. Although it had been training for several months, the new corps, officially styled the Victoria Battery of Garrison Artillery, did not receive official authorization until July 19.[38]

Upon his arrival in Victoria, Irwin met with the Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Squadron, Rear-Admiral A. F. R. de Horsey, who appointed a small group of Royal Navy and Royal Marine Artillery officers to co-operate with Irwin on the siting of the batteries. These officers went over the ground quite thoroughly in the following weeks, and although the naval and military views on defence sometimes differed, there was a much greater area of agreement.

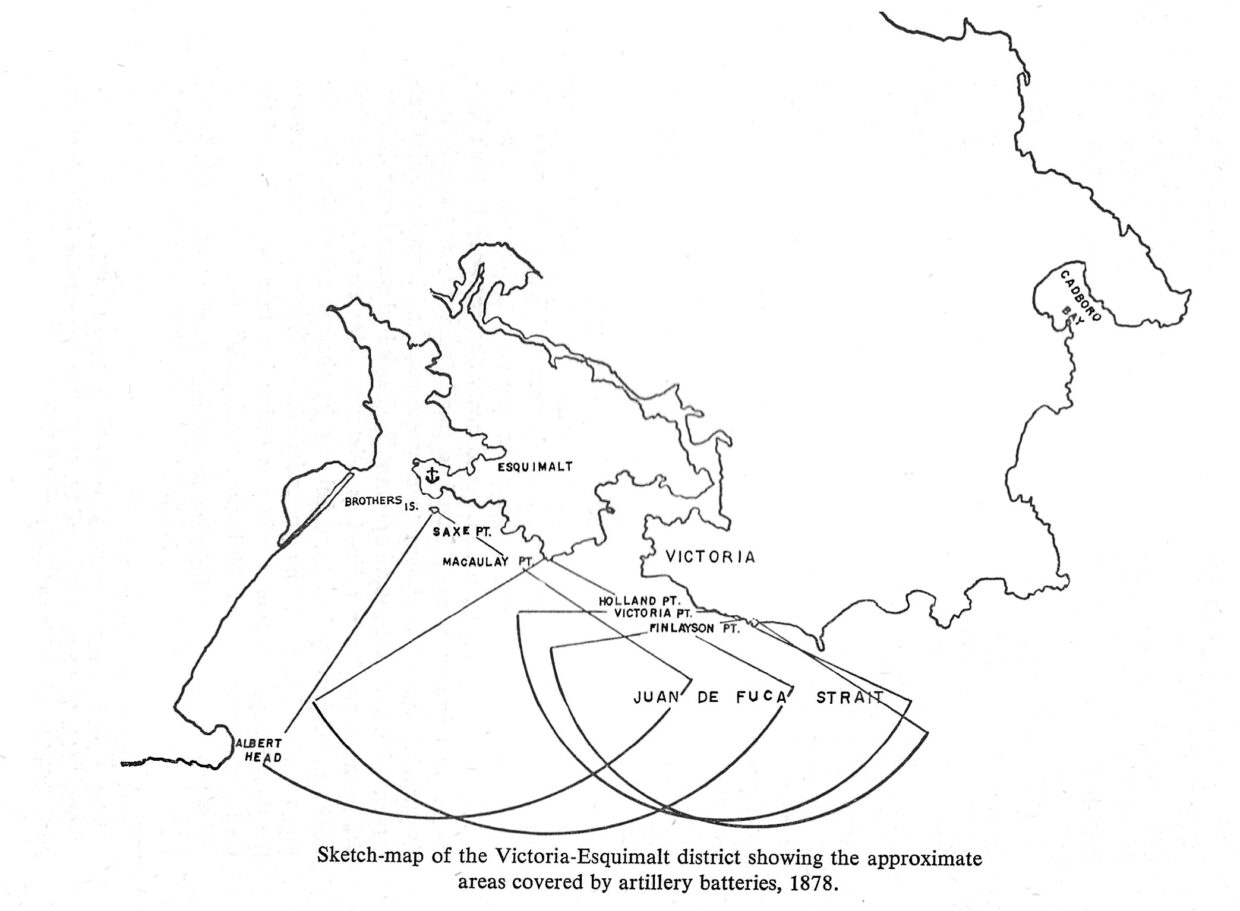

Before leaving Ottawa, Irwin had been given the plans for a proposed system of defence drawn up by Lieutenant-Colonel Blair three years previously. Blair had envisaged one battery at Victoria Point (at the base of Beacon Hill) commanding the approach to Victoria Harbour; one at Macaulay Point, which would cover the entrance to both harbours; and one on Fisgard Island, a small rocky isle at the mouth of Esquimalt Harbour. Of these three positions, the Macaulay Point battery was felt to be the most important.[39] Work had started on this latter site even before Irwin arrived in Victoria. However, for some time work on the battery had been held up by the owners of the site, the Puget Sound Company, who demanded $2,000 for the 1 5/8 acres needed for the battery. In June, Irwin was ordered to take possession of the land and construction of the battery continued.[40]

While waiting for permission to continue work at Macaulay Point, Irwin received authority to begin construction of a battery at Victoria Point. For various reasons two 2-gun batteries were constructed at the sea base of Beacon Hill — one to command Ross Bay on the east, the other to guard Victoria Harbour on the west. Irwin had wanted to place one of these batteries on Holland Point, where the guns would have a greater arc of fire. However, it would have cost $400 to purchase the necessary land, whereas the positions at Finlayson and Victoria Point at the sea base of Beacon Hill were owned by the Government.[41]

The naval view of the proper location of the various batteries differed in several respects. Although he did not deny the potential usefulness of the batteries under construction for the defence of Victoria, Admiral de Horsey pointed out that owing to the shallowness of the harbour no enemy ship of any size could enter it. Further, he added:

“In the absence of defensive works of any extent not now contemplated, that city is not defensible except by sufficient land forces to meet an enemy in the field. … It will be seen how easily it can be taken in the rear by an enemy landing in Cadboro Bay, Cormorant Bay or indeed anywhere along a coastline of some 13 miles or more extent, and yet with a march of only 3 to 5 miles of that city.”[42]

Moreover, the admiral was interested in having the batteries arranged so as to be able to bring their fire to cover the approaches to Esquimalt Harbour and the harbour itself. The final result was that the proposed battery on Fisgard Island was dropped, since the rocky nature of that island would make the construction of a battery there extremely expensive. Brother’s Island, also located at the mouth of Esquimalt Harbour, was chosen as an alternative site.

By the end of August, after three months of steady labour, the batteries were completed. The two strongest were those on Brother’s Island and Macaulay Point. The former held one 8-inch 9-ton and two 64- pounder R.M.L. (rifled muzzle-loading) guns, while the latter had three 7-inch 6Vi-ton R.M.L. guns. The two batteries at the base of Beacon Hill each had two 64-pounder R.M.L. guns. All the guns were mounted en barbette behind earthen breastworks, and each battery had a small expense magazine and an additional wooden building to hold various small stores needed to work the guns. The four largest guns were enclosed in weather-proof wooden sheds, triangular in section, to protect the guns, slides, and carriages from the elements.[43]

Even as the batteries were being built, it was obvious that the problem of manning the guns was not solved with the enrolment of fifty volunteer artillerymen. Irwin had warned his naval associates that with this number he could barely man five guns, and these would naturally be, as all the men were enrolled and drilled in Victoria, the batteries at Beacon Hill and Macaulay Point.[44] The question of getting sufficient trained men to serve the batteries was to be raised time and again for the next decade.

There had been little trouble in enrolling men to volunteer for the new artillery unit when it was first formed, but the militia rifle companies had suffered as a consequence. Houghton reported at the time that artillery drill and practice was much more to the taste of the young men of Victoria, and this, together with the attractive blue tunics worn by the gunners, made it the popular corps with recruits. Even men who had put in their three years with one of the rifle companies had joined the artillery.[45]

Moreover, the militia commander had grave doubts as to whether they could be properly trained to man the guns and maintain an effective fire against armed ships in motion. The naval commander had further objections. In a letter to the Admiralty, he wrote:

“. . . Esquimalt should be defended by Imperial resources and under naval control. The Dockyard is Imperial property and bears the same relative position to our Squadron in the Pacific as Halifax does to the Squadron in the North Atlantic, but with three-fold force as there is no Bermuda or Jamaica in these waters, no British possession within possible reach for supplies and repairs. It is lamentable to think that in the present defenceless condition of this harbour and viewing the trifling number of Volunteer Militia, any fairly organized enemy’s expedition should suffice to destroy the dockyard and be master of the position until again ejected by hard fighting.”[46]

For their separate reasons, therefore, both the militia and naval commanders recommended that a force of 100 marine artillerymen should be stationed at Esquimalt to take charge of the coastal batteries. Their recommendation to establish a permanent artillery corps came at a poor moment. In Europe the Congress of Berlin had restored at least a temporary calm in the Balkans as Briton and Russian faced each other across a conference table instead of a battlefield. As tension eased, less attention was paid to the need of a permanent artillery corps for Esquimalt. The only result was that permission was given the Victoria Battery of Garrison Artillery to increase its establishment to five officers and eighty-five other ranks.[47]

During the latter part of 1878 Great Britain tried to interest Canada in sharing the expense of erecting permanent works for the defence of Esquimalt and Victoria, and suggested an Imperial and a Canadian officer should jointly examine and report on the defensive needs of British Columbia. The Dominion Government stated that it was unable to take upon itself a share in the cost of erecting permanent defences but agreed to co-operate in a military survey of the Pacific Coast. The British representative selected was Colonel J. W. Lovell, R.E., then stationed at Halifax, while the Senior Inspector of Artillery, Lieutenant- Colonel T. B. Strange, R.A., represented Canada.

Colonel Lovell made a very thorough inspection of the defences of British Columbia in 1879, and in his report made recommendations which, if carried out, would have made Esquimalt a second Halifax. Of the temporary batteries he wrote: “As neither the excavations for the batteries nor the material of which they are constructed could be utilized in permanent works, and the sites do not seem adapted for such works, I would recommend that the batteries should be left as they are in charge of the Dominion Government. . . “[48] The sites he selected for locating permanent batteries were, with one exception, chosen to provide for the defence of Esquimalt rather than Victoria. At Sangster’s Knoll and Cape Saxe, both close to Esquimalt, he would have a battery of six 10-inch guns, on Rodd Hill six 7-inch guns, and on Signal Hill, a feature commanding Esquimalt Harbour and the land approaches to the peninsula where the naval base was located, he suggested placing two 10-inch guns. All these formidable batteries commanded the sea approaches to Esquimalt and Esquimalt itself. For Victoria, Colonel Lovell proposed a battery of six 10-inch guns atop Beacon Hill.

Nor was this all. To defend the Esquimalt base against an attack by land, Lovell suggested that twelve field guns—40- or 20-pounder Armstrong guns—should be accessible to the garrison. In addition, he thought one or two armour-plated gunboats stationed permanently at the naval base would help to prevent an enemy landing, and, further, that the mouth of Esquimalt Harbour should be protected by a system of torpedo defence in time of war. Finally, the British representative recommended the establishment of a means of telegraphic communication from Victoria and Esquimalt to the Strait of Juan de Fuca and around the coast to the north of the Saanich Peninsula.

To man these defences, Colonel Lovell believed there ought to be a minimum garrison of 1,138 Imperial regular soldiers in the Province. Of this number, 120 would be Royal Engineers, 20 of whom would be specially trained as submarine miners to take care of the torpedo (or mine) defence. He felt, too, that 900 Imperial infantrymen were needed to repulse an attack by land, and that at least 118 Royal Artillery men were needed to man the batteries. Both latter corps would be assisted in their duties by the militia. For example, 500 militia infantrymen would be raised locally to co-operate with the Imperial force. As for the artillery, Lovell thought each battery should be served by a force which would be one-third regular and the remainder militia artillerymen, with an additional reserve of militia totalling one-third of the entire force also drawn from the local populace. Thus, in addition to the 1,138 Imperial troops, Lovell would have Victoria provide an additional force of 854 militiamen!

On the special request of the British Government, Colonel Lovell went on to visit Nanaimo, New Westminster, and Burrard Inlet (Vancouver) . For Nanaimo he proposed another permanent Imperial garrison to man from six to nine heavy guns which he felt were necessary for the defence of that important coal-mining town. As an alternative, he suggested placing eight 40-pounder Armstrong guns there, which, evidently, he would have manned by the militia. He thought a few field guns and water obstructions would be sufficient to protect New Westminster from an attack by gun-boats coming up the Fraser River; and for Burrard Inlet, he believed the harbour entrance could be well protected by a battery on the high ground on each side of the First Narrows, together with additional batteries on Points Grey and Atkinson to cover English Bay.

In summing up his report, Colonel Lovell stated bluntly that the Pacific Province could not be protected from an invasion from the south, as indeed it could not. He added, too, that the greatest need for the defence of British Columbia was the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway and an all-Canadian telegraphic route.[49]

The report by Lieutenant-Colonel Strange on the defensive needs of British Columbia was, in many respects, similar to that made by Colonel Lovell.[50] Strange, too, believed it essential to establish a system of telegraphic communication around the southern tip of Vancouver Island to warn of an enemy’s approach. Further, he saw the need of some sort of torpedo defence for Esquimalt Harbour. He felt, however, that four rather than twelve field guns in the hands of the militia artillerymen would suffice to meet and defeat an assault from the sea. Strange also advocated the construction of batteries on Signal Hill and Rodd Point, but he would make the Brother’s Island battery permanent. To give Victoria further protection, he recommended the construction of a battery on Holland Point. A type of keep or blockhouse on Belmont and Beacon hills—both high features a few hundred yards behind the Rodd Point and the Victoria batteries respectively—would, Strange reported, secure the rear of these batteries from attack.

To man these and the existing batteries, Strange thought it necessary to have 200 marine artillerymen at Esquimalt working under naval control, and an additional permanent garrison of 100 men at Victoria to man the batteries there. To increase the number of militia artillerymen and to better their instruction and training, Strange proposed that a four-battery brigade of garrison artillery should be formed. The existing battery in Victoria would be complemented by changing No. 1 Company of Rifles, Victoria, into a second battery. A strengthened Seymour Battery would make a third, and a new battery to be raised at Nanaimo would make a fourth. Of all the recommendations made by both officers, a variation of Strange’s last proposal was the only one acted upon in the next four years.

Although the pressing need of a permanent garrison of artillerymen continued to be brought before the Dominion Government in the following years, the more immediate problem of providing sufficient militia gunners to man the temporary batteries was foremost in Lieutenant- Colonel Houghton’s mind. To furnish these men, he endorsed the Artillery Inspector’s plan to convert the riflemen to gunners. At the annual muster in 1879, although each rifle company had an authorized strength of two officers and forty other ranks, both companies could parade no more than a total of thirty-one all ranks. The Victoria Rifles, Houghton wrote, were being ” annihilated by absorption,” and the only remedy was to convert them into artillery batteries of fifty or sixty men each, thus forming a three-battery Brigade of Garrison Artillery in Victoria.[51]

The attempt to strengthen the gun crews by increasing the authorized strength of the existing battery from fifty to eighty-five was found to be unsatisfactory. From the beginning the battery commander, Captain Dupont, felt that since his was the most popular corps, he could be selective. Thus, when he was authorized to raise an additional thirty-five men for his corps, he made little attempt to do so until he received sufficient uniforms to clothe the recruits properly. Also, until 1881 he insisted that the recruits must be of the regulation height for the artillery. His attempt to enrol only permanent residents of Victoria and so avoid the expense and waste of training men who would soon move on to greener fields, was another factor that tended to keep the battery from reaching its full strength. Nevertheless, the battery continued to be one of the best units in British Columbia during its existence, and the enthusiasm of the men for their corps was remarkable. In 1880, for example:

“They . . . established a school of arms in the battery and rented a building for this purpose, where lessons in broad sword, single stick, fencing and boxing are given one night in each week during the winter season. The necessary material for the school was imported from England, and the expense of the purchase, as well as rent, fuel, and pay of instructors, etc., was provided by members of the Battery by general subscription.”[52]

The reorganization of the British Columbia artillery did not take place for several years owing mainly to a change in staff officers. In October, 1880, Lieutenant-Colonel Houghton was transferred to Military District No. 10, with headquarters in Winnipeg, where, ultimately, he later played an important part in the Riel Rebellion.[53] For over two years British Columbia lacked a permanent Deputy Adjutant-General. Captain Dupont attempted to carry on the duties of Deputy Adjutant- General, but during the absence of a permanent officer in that post the British Columbia militia did little more than hold its own against indifference in Ottawa and apathy at home.

More serious than the modest turnout for drill and annual training was the deterioration of the military equipment and faculties. Both the drill halls in Victoria and New Westminster were now inadequate and in serious need of repair. Indeed, the latter was only kept in a useable state by the support of the population of the town, who held their public meetings in it. The guns used by the Seymour Battery were in such bad shape that the battery commander feared for the gunners’ safety if the guns were fired. Even the coastal batteries around Victoria suffered from neglect. As Captain Dupont wrote in 1881: ” There are no fences around the batteries and cattle range over the parapets and tramp them down, mischievous persons take out and throw away the quoins and tampions and fill the guns with sticks and stones, hence everything movable is taken away and kept under key.”[54]

A change for the better in British Columbian military affairs came with the appointment of Captain (Brevet Major) J. G. Holmes, “A” Battery, Royal School of Gunnery, to the position of Acting Deputy Adjutant-General of British Columbia in 1883.[55] Holmes arrived in Victoria on May 1, and immediately set to work to bring a greater degree of military efficiency to his new command. He visited the militia companies, talked with their commanders, reviewed the recommendations made by Lovell and Strange, and made a report to Ottawa on his findings.

Holmes’s first major success came late in 1883, when he succeeded in having the authorities in Ottawa order the establishment of the British Columbia Provisional Regiment of Garrison Artillery.[56] This regiment was to consist of four batteries: No. 1 Battery was formed from the old Seymour Battery; Nos. 2 and 3 were created by dividing and strengthening the existing garrison artillery in Victoria; and No. 4 was formed from No. 1 Company of Rifles, Victoria.

The establishment of this militia artillery regiment came hard on the heels of another important event in British Columbia’s military affairs, for two months previously the first Canadian Permanent Force militia unit to be stationed in the Province was authorized to be raised in Victoria. This new artillery unit, together with other infantry and cavalry units, was authorized by the Militia Act of 1883, an Act necessitated by the obvious need for additional Permanent Force militiamen to provide the long-neglected caretaker and instructional service given by Imperial regular troops up to their withdrawal in 1871. Prior to the passing of this Act, there existed only two Permanent Force artillery batteries in Canada, “A” and “B” Batteries, stationed at Quebec and Kingston. The formation of a third, or “C” Battery, which with the others would form the first Regiment of Canadian Artillery, was discussed as part of the Militia Act in the House of Commons in April. The establishment of the new battery was urged on the grounds that it would serve as a needed additional school of gunnery instruction rather than as a military necessity for British Columbia. ” C ” Battery, Regiment of Canadian Artillery, was authorized to be organized at Victoria on August 10, 1883.[57] Captain Holmes was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-colonel and was given the command of the battery while continuing to act as Deputy Adjutant-General.

It would appear that, with the authorization of ” C ” Battery, those responsible for militia affairs in Ottawa believed a major gap in the defence of British Columbia had been filled. However, a new problem arose which was to hamper the actual formation of ” C ” Battery for another four years—the problem of recruiting sufficient men in Victoria to serve in the permanent militia.

At the time recruiting for the new battery commenced, British Columbia was in the midst of a railway boom which provided good wages and steady employment for its relatively scanty population. Thus, only a handful of men were interested in enlisting in the artillery unit at a time when much higher wages could be gained in private employment. As the months went by with no change in the situation, the Minister of Militia and Defence, the Honourable A. P. C. Caron, seized upon an idea presented to him by Captain J. R. East, R.N. This officer had accompanied the Marquis of Lome to British Columbia when the latter visited Victoria in 1882, and he had discussed the matter of Pacific defences with Lome when they met in London in the summer of 1884. In a letter to Caron, East suggested that the Canadian Government should enlist pensioners from the Royal Navy and Royal Marines to fill the ranks of “C” Battery. These men, all having artillery training, should be induced to settle in Vancouver Island and other special points in British Columbia, and thus, wrote East, the Dominion would have available on the Pacific Coast a body of trained gunners already accustomed to discipline. Moreover, such men, drawing a life pension of from £30 to £50 per annum, would not risk losing their pension by deserting or by moving to the United States.[58]

This novel scheme was adopted by Caron as one which would provide a permanent, well-trained force to man the guns at Esquimalt and Victoria and, at the same time, would make available a cadre of instructors which otherwise would be most difficult to find in Canada. The British Government was sounded out and favoured the proposal. The Admiralty, however, while waiving any objections to the pensioners retaining their pension while serving in the Canadian militia, refused to accede to Caron’s request that, pending completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway, British war vessels transport the men to British Columbia. The Admiralty was then asked if they would transport the men to Halifax in the spring of 1886, an alternative which the Admiralty favoured provided the Canadian Government would bear a share of the cost, estimated at £300. Canada in turn suggested that Britain should transport the pensioners to Halifax free of charge since the Canadian Government would bear the greater expense of taking them to Victoria via the Canadian Pacific Railway.[59]

While this haggling over the transportation question was going on, Caron visited England and in July, 1886, went to see Lord George Hamilton, the First Lord of the Admiralty, on the subject. Agreement as to the principle of recruiting British pensioners for British Columbia was again confirmed, but there was a mass of detail which remained to be cleared up after Caron’s departure. It was not until July of the following year that recruiting posters for ” C ” Battery were put up in England, and then it was found that on the posters someone had made the mistake of asking for unmarried pensioners. Since most of the pensioners were married, it was scarcely remarkable that the recruiting campaign was a dismal failure. As a result, Caron informed the British authorities to take no further steps in the matter, and eventually he secured recruits for ” C ” Battery from the permanent artillery batteries stationed in Quebec and Kingston.[60]

In the four years between the authorization and actual organization of ” C ” Battery, Lieutenant-Colonel Holmes had been partially successful in his efforts to strengthen the efficiency of British Columbia’s defences. During this period various additional recommendations were made by naval and military officials regarding the number and siting of the coastal batteries defending Victoria and Esquimalt. None of these was acted upon by the Canadian Government. Holmes, meanwhile, concerned himself mainly with the condition of the existing batteries, all of which were in need of repair. The carriages, slides, and platforms of several of the heavier guns were becoming unserviceable from decay. Moreover, he warned, the militia was dependent on the naval magazine at Esquimalt for ammunition to serve the batteries. ” We have less than 100 rounds per gun for the 7-inch and 8-inch guns,” he reported, ” and hardly any for the 64-pounders. At least 400 rounds per gun should be always in reserve for these guns.“[61] To add to his difficulties, the Royal Navy was in the process of adopting a new pattern of gun, and thus even the small quantity of available ammunition was liable to depletion without replacement. For somewhat the same reason, Holmes recommended that the British Columbia militia should be issued with Martini-Henry rifles. The Royal Navy and Marines now used these new weapons, and consequently the largest amount of rifle ammunition on the Pacific Coast—that held in the naval magazine—was of the Martini-Henry pattern. The problem of defending Victoria from the rear led Holmes to suggest that his command be supplied with four field guns, a recommendation made several years previously by Colonels Lovell and Strange. One of these guns Holmes would issue to the Seymour Battery, while the others he would hold in Victoria.[62]

For several years Holmes was unable to secure either the new guns he wanted or repairs to the existing batteries. Nor was he able to accept the services of interested groups of men in Nanaimo, Burrard Inlet, and several towns in the Interior of the Province who offered to raise artillery and mounted rifle companies to be incorporated in the militia. These offers, recommended by Holmes, had to be turned down owing to the parsimonious budget allowed the Militia Department.[63]

It was not until the spring of 1885, following yet another scare of a war between Russia and Great Britain—this time over Afghanistan— that Ottawa was willing to spend additional money on British Columbia defences. In Victoria the war scare created the usual alarm over the defenceless state of the Province. One gentleman, a retired naval officer, advocated the formation of one or two companies of mounted volunteers, armed with field-pieces or Gatling machine-guns, to protect the city from an attack in the rear.[64] The Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Station, Rear-Admiral J. K. E. Baird, was moved to review the defences of Esquimalt and made several recommendations regarding necessary additional coastal and field guns.[65] Various public meetings were held in Victoria which, together with newspaper editorials, expressed concern over the exposed position of the Provincial capital, and both the Victoria Municipal Council and the British Columbia Executive Council asked the Dominion Government to strengthen British Columbia defences. However, as Holmes pointedly reported, very few persons came forward to assist themselves by joining the men already enrolled in the Active Militia.

The Federal Government took the minimum precautionary measures possible to combat any attack. Sufficient funds were advanced for the repair of the coastal batteries, but that was all. The ammunition problem remained a matter of grave concern to the artillery commander, who realized that, should an actual attack be made, all the available ammunition would be expended in a matter of a few hours. No action was taken to implement the recommendations made by Holmes and other senior militia officers regarding additional arms and equipment necessary for the proper defence of the Pacific Coast. Indeed, probably the only important result of this war scare for British Columbia was that it renewed Imperial interest in the defence of Esquimalt and focused attention on the necessity of a firm British-Canadian plan of defence for the naval base.

The greatest and most significant addition to the real and potential strength of the defences of the Province came with the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway in November, 1885. The rapid transportation of militia and supplies from the Eastern Provinces to crush the Riel Rebellion had already demonstrated the strategic importance of the railway to the nation. When completed in the latter part of the year, it assumed an important place in Imperial strategic planning as well. For those charged directly with the task of defending British Columbia, the termination of the all-Canadian transportation and communication route brought additional responsibilities as well as additional strength. The story of how these new responsibilities were met is beyond the scope of this paper. It must suffice to note that then, as now, the militia continued to look to the sea-coast rather than the border for the approach of a potential enemy.

Reginald H. Roy.

Provincial Archives, Victoria, B.C.

[1] The first detachment of Royal Engineers to be sent from England to British Columbia arrived in the colony in 1858. Of a total of 165 who came, about 130 decided to remain in the colony when their detachment was disbanded in 1863. F. W. Howay, The Work of the Royal Engineers in British Columbia, 1858 to 1863, Victoria, 1910, p. 11. British Columbia Historical Quarterly, Vol. XVIII, Nos. 1 and 2.

[2] In March, 1875, when the Provincial Government handed over its obsolete military stores to the Department of Militia and Defence, 496 Brunswick Short rifles and 289 Enfield Long rifles were included in the transfer. These weapons were far inferior to the breech-loading Snider-Enfield rifles provided the Canadian militia in 1867. Public Archives of Canada, Papers of the Deputy Minister of Militia and Defence, Letters Received, 1875, No. 01424. (Hereafter this source will be cited as D.M. Papers.)

[3] Ibid., No. 6278. This docket contains all the correspondence between Trutch and the Secretary of State for the Provinces, Joseph Howe, regarding the Fenian scare in Victoria, together with enclosures sent to Howe relating to Trutch’s correspondence with Captain Cator and others.

[4] Loc. cit.

[5] H.M.S. Boxer, commanded by Lieutenant-Commander F. W. Egerton, was a composite-built screw gun-vessel mounting four guns.

[6] H.M.S. Sparrowhawk, commanded by Commander H. W. Mist, was a somewhat heavier and more powerful gun-vessel than the Boxer but carried the same number of guns.

[7] H.M.S. Scout, commanded by Captain R. P. Cator, was a screw-propelled corvette carrying seventeen guns. Its displacement (2,187 tons) and power (1,327 horsepower) were respectively more than triple and double that of the gun-vessels.

[8] D.M. Papers, No. 6278, Cator to Trutch, January 2, 1872; Trutch to Cator, January 3, 1872.

[9] The Victoria Volunteer Rifle Corps was in no condition to act in this crisis. A local newspaper commented on the unit as follows: “It is problematical to what extent it would be safe to rely upon this force as a means of repelling a Fenian invasion. If we are correctly informed that it has lapsed into a torpid state, it would, perhaps, be wisest not to count upon it at all as a means of defence.” Victoria Colonist, January 4, 1872.

[10] DM. Papers, No. 6278, Cator to Trutch, January 7, 1872.

[11] Ibid., Trutch to Howe, January 2, 1872. In this letter Trutch wrote that, aside from the warning letter he had received, ” certain significant though inexplicit rumours … of late reached us from San Francisco of some contemplated Fenian movement in this direction. . . .”

[12] Minute of the Executive Council of British Columbia, January 2, 1872, enclosed in ibid.

[13] D.M. Papers, No. 6278, Trutch to Howe, January 9, 1872. Four days before sending this message, Trutch had telegraphed Sir John A. Macdonald outlining the measures he had taken. The Prime Minister, in a personal letter to the Governor-General on January 18, suggested that the Fenian “scare” would be sufficient grounds for repeating the request to the British Admiralty to retain the Sparrowhawk at Esquimalt for another season. Public Archives of Canada, G 20, Vol. 140, No. 2286, Macdonald to Lisgar, January 18, and enclosed telegram, Trutch to Macdonald, January 5, 1872.

[14] Public Archives of Canada, Gl, Vol. 185, p. 32, Kimberley to Lisgar, January 4, 1872. These instructions reached Ottawa sixteen days later. On that day Trutch had written Macdonald: ” I do trust you are intending to do something at once to put us in a more decent state of defence. . . . We ought to have not only a detachment of permanently embodied militia quartered here but a fort for the protection of the entrance to Esquimalt and Victoria Harbour garrisoned by a proper force of artillery.” Public Archives of Canada, Macdonald Papers, Vol. 278, pp. 150-151.

[15] D.M. Papers, No. 6322, enclosures, Trutch to Cator, January 31, 1872.

[16] British Columbia was designated Military District No. 11 on October 16, 1871. Militia General Orders, October 16, 1871. (Hereafter cited as M.G.O.)

[17] D.M. Papers, No. 6279, Memorandum, Robertson-Ross to Cartier. These stores cost approximately $50,000. The arms, etc., were shipped direct from England to Victoria

[18] D.M. Papers, No. 6521, Houghton to Cartier, April 22, 1872. Another applicant for the vacancy was Captain W. A. Delacombe, who at this time was in charge of the detachment of Royal Marines on San Juan Island. This officer’s application was supported by the signatures of over 200 residents of Victoria. Houghton’s political supporters, however, carried more weight and influence in Ottawa. See also ibid., Nos. 6708 and 7785.

[19] Department of Militia and Defence, Report on the State of the Militia of the Dominion of Canada . . . 1872, Ottawa, 1873, p. cxxvi. (Hereafter cited as Militia Report with the appropriate year.) This inspection tour across Canada by Robertson-Ross was probably the most remarkable tour ever made by an Adjutant- General of the Canadian Forces. See R. H. Roy, ” The Colonel Goes West,” Canadian Army Journal, VTII (1954), pp. 76-81.

[20] M.G.O., No. 6, March 28, 1873.

[21] M.G.O., No. 3, February 13; No. 8, April 11, 1874.

[22] D.M. Papers, No. 9937, enclosure, Houghton to Colonel Powell, May 4, 1874. Colonel Powell succeeded Robertson-Ross as the Adjutant-General of Militia.

[23] Ibid., enclosure, Lieutenant Prior to Houghton, June 11, 1874. Prior was second in command of No. 1 Company of Rifles, Nanaimo, when it was posted in orders on September 11, 1874.

[24] M.G.O., July 10, 1874.

[25] D.M. Papers, No. 0433,Building Agreement, Victoria Drill-shed.

[26] Ibid., No. 02385.

[27] No. 1 Company of Rifles, Nanaimo, was finally disbanded on May 2, 1884.

[28] Militia Report . . . 1875, Ottawa, 1876, pp. vi-viii.

[29] D.M. Papers, No. 02638, Colonel G. F. Blair, “Memorandum on the Defence of British Columbia.” In 1875 the Intelligence Department of the British War Office asked for detailed reports from the colonies. In Canada the commander of each military district submitted a report, and Colonel Blair’s served for British Columbia. Among other steps he suggested to place British Columbia in a proper state of defence, Blair recommended the purchase of Alaska “if possible,” the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, and the establishment of a British garrison at Esquimalt.

[30] Loc. cit.

[31] C. F. Hamilton, “The Canadian Militia: The Dead Period,” Canadian Defence Quarterly, VH (1929), pp. 78-89.

[32] Militia Report . . . 1877, Ottawa, 1878, p. 274.

[33] D.M. Papers, No. 04375, enclosure, Colonial Office, Secret Circular Dispatch, March 11, 1878. In Canada the warning was probably more applicable to Victoria and Esquimalt than to other Canadian ports.

[34] Victoria Colonist, February 9, 1878.

[35] Ibid., February 17 and 20, 1878.

[36] D.M. Papers, No. 04441, confidential, Smyth to the Honourable A. G. Jones, Minister of Militia and Defence, May 3, 1878. For further details of the Cimbria affair see L. I. Strakhovsky, ” Russia’s Privateering Projects of 1878,” The Journal of Modern History, VTI (1935), pp. 22-40.

[37] Public Archives of Canada, G21, No. 165, Vol. 3, secret, Hicks-Beach to Dufferin, May 11, 1878, and the enclosed Colonial Office print, secret and confidential, ” Report of a Colonial Defence Committee on the Temporary Defences of the Naval Station of Esquimalt and the Important Commercial Town and Harbour of Victoria,” April, 1878.

[38] M.G.O., July 19, 1878.

[39] D.M. Papers, No. 04470, Smyth to Irwin, May 11, 1878.

[40] Ibid., Smyth to Scott, June 29, 1878. The Honourable R. W. Scott was Acting Minister of Militia and Defence at this time.

[41] Ibid., same to same, June 29 and July 20, 1878.

[42] Public Archives of Canada, MG13, A 6, Vol. 4, 285a-287, de Horsey to the Secretary of the Admiralty, July 28, 1878.

[43] Militia Report . . . 1878, Ottawa, 1879, pp. 306-312. For an appreciation of Lieutenant-Colonel Irwin’s work in Victoria see J. F. Cummins, “Colonel D. T. Irwin, a Distinguished Artillery Officer,” Canadian Defence Quarterly, V (1928), pp. 137-141.

[44] Public Archives of Canada, MG13, A 6, Vol. 4, 288-296. Bedford to de Horsey, June 27, 1878. Captain F. D. G. Bedford, R.N., was chairman of the board of officers appointed by Admiral de Horsey to co-operate with Lieutenant- Colonel Irwin.

[45] Militia Report . . . 1878, Ottawa, 1879, p. 214.

[46] Public Archives of Canada, MG 13, A 6, Vol. 4, 286-287, de Horsey to the Secretary of the Admiralty, July 28, 1878.

[47] M.G.O., August 1, 1878.

[48] Public Archives of Canada, Colonel J. W. Lovell, ” Report on the Defences of Esquimalt and Victoria, December 1879,” in ” Correspondence of the Committee on the Defences of Canada, 1886.” Vol. VI, p. 437.

[49] Ibid., pp. 440-446.

[50] Lieutenant-Colonel T. B. Strange, “Report on the Defences of British Columbia, November, 1879,” in ibid., Vol. VI, pp. 416-425.

[51] Militia Report . . . 1879, Ottawa, 1880, pp. 214-218.

[52] Militia Report . . . 1880, Ottawa, 1881, p. 67.

[53] M.G.O., No. 20, October 15, 1880. Colonel J. W. Laurie was appointed to replace Houghton, but he was on an extended leave and retired from the militia in 1882 without taking over the post. Ibid., No. 2, February 3, 1882.

[54] Militia Report . . . 1881, Ottawa, 1882, pp. 62-63.

[55] M.G.O., No. 7, April 13, 1883.

[56] Ibid., No. 22, October 12, 1883.

[57] Ibid., No. 18, August 10, 1883.

[58] Public Archives of Canada, East to Caron, luly 8, 1884, in ” Correspondence of the Committee on the Defences of Canada, 1886,” Vol. VI, pp. 851-855. At a later date, pensioners from the Royal Artillery were included in the proposal.

[59] Correspondence with Imperial Authorities Respecting the Enlistment of Pensioners from Royal Navy and Marines for Service … in British Columbia, 1884-1885,” in ibid., Vol. VI, pp. 849-917. This correspondence, covering the period from 1885 to 1887, is continued in D.M. Papers, No. A3167.

[60] Ibid., Caron to Tupper, September 23, 1887; M.G.O., No. 16, October 6, 1887.

[61] Militia Report . . . 1885, Ottawa, 1886, p. 56.

[62] Militia Report . . . 1883, Ottawa, 1884, pp. 51-54. The Seymour Battery was to remain without new armament for a number of years. Of this battery, Holmes wrote: ” How the officers and men manage to maintain interest in their work, with their present obsolete weapons, mounted on rotten carriages, I can hardly imagine.” Militia Report . . . 1885, Ottawa, 1886, p. 56.

[63] Public Archives of Canada, Adjutant-General’s Correspondence, Letters Received, Nos. 04710, A449, and A488; Militia Report . . . 1885, Ottawa, 1886, pp. 54-57.

[64] DM. Papers, No. A1518, Baker to Caron, May 2, 1885; Victoria Weekly British Colonist, April 17, 1885.

[65] Public Archives of Canada, Adjutant-General’s Correspondence, Letters Received, No. 09577, Baird to Holmes, April 4, 1885. Among other measures, Baird recommended the construction of a telephone-line between the batteries. Holmes asked for and received permission to construct such a line, but was told by the Adjutant-General: “Of course this expenditure [$1,000] will not be made unless war is actually declared.” Ibid., Letters Sent, Vol. 46, p. 683, Powell to Holmes, May 5, 1885. A good idea of the condition of the Canadian militia after ten years of such penurious restrictions may be gained from G. F. G. Stanley, Canada’s Soldiers, 1604-1954, Toronto, 1954, pp. 263-264.